TRACING DE SOTO'S JOURNEY

|

|

En español: Trazando el viaje de De Soto

|

August 2022

Bradenton, Fl.

|

|

But once you go out to explore the jungle on the "De Soto Expedition Trail," you find life size images of Native Americans and conquistadors scattered throughout the place. You are not just trekking through a tropical forest here; from the markers along the way, you are getting an education!

Here you learn that, in 1538, Spanish King Charles V granted De Soto a royal contract to govern Cuba and “conquer, pacify and populate” La Florida - the land that Juan Ponce de Leon had discovered in 1513 and failed to conquer when he returned in 1521. And the land that another conquistador, Panfilo de Narvaez, had also failed to conquer 1528. |

|

You learn that De Soto was already a wealthy and renowned conquistador from having plundered the Inca empire in Peru, that he invested his fortune on the new expedition and came to Florida seeking similar fortune. You learn that he led a nine-ship flotilla with close to 700 men, a few women, 350 horses, a herd of pigs, several packs of bloodhounds and "equipment necessary to sustain an expedition of conquest."

Since La Florida was then understood to be much bigger than the current State of Florida, De Soto understood his commission to cover limitless territory. And so you learn that "in their relentless pursuit of gold and riches," De Soto's army spent the next four years exploring "much of the interior of southern United States, from Florida to Texas." |

|

You learn that De Soto first established a base camp at the Indian village of Uzita, and within this park, you visit a small replica of the Uzita camp.

You learn that this lush mangrove forest once covered much of the Tampa Bay coastline and presented an almost impenetrable obstacle for the De Soto expedition. As I explain in a Chapter 49, On the Trail of Conquistadors, because they were cutting through mangroves, while herding pigs, horses, war dogs and fighting natives who stood in their way, it took them three months just to reach the Florida panhandle - less than a five-hour drive nowadays! |

|

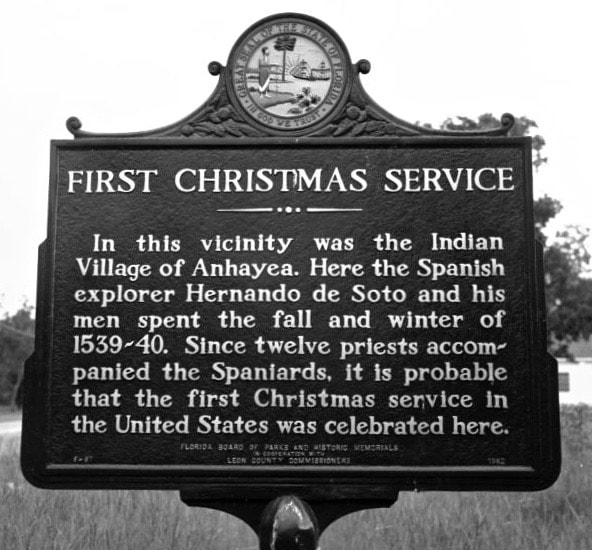

When they reached the Apalachee village of Anhaica, in what is now Tallahassee, Fl., they fought with the natives, settled for the winter, and celebrated the first Christmas in what is now the United States. See: America's First Christmas was Celebrated in Spanish.

Their four-year, 4,000-mile hike finally lost its drive when De Soto died of fever and was buried in the Mississippi River in 1542. In this park you see that, contrary to popular belief, Florida natives were already a warring people when the Spanish arrived. You learn that before the Spanish raided Indian villages, the Indians were already raiding each other's villages. On the contrary, you also learn that De Soto had vowed to kill any Indian who would dare lie or betrayed him. |

|

Clearly, this park tries to be objective in its presentation of the Spanish conquistadors and those first encounters with native Americans. Without holding back, it shows that both were equally violent. Two more examples:

“Emboldened by the conquest of the gold-rich Aztec and Inca civilizations in Central and South America several years earlier, the Spaniards came prepared for battle with armor, helmets, arquebus, crossbow, lance or pike in hand, some on horseback or with war dogs,” one marker explains. “Those people are so warlike and so quick,” another marker quotes a conquistador. “Before a crossbowman can fire a shot, an Indian can shoot three or four arrows, and very seldom does he miss what he shoots at.” This park asks you to deal with the reality of living in 16th-century Florida! |

Hernando De Soto

|

De Soto's winter encampment in Tallahassee, site of first American ChristmasComing from Hernando de Soto's landing site in Tampa Bay and heading north to follow the trail of his 1539-1543 expedition, I would be remiss to leave Tallahassee before noting that this is the site of De Soto's winter encampment, where historians believe America's first Christmas was celebrated — in Spanish!

It was recognized as the location of "America's First Christmas celebration" by the Florida House of Representatives in 2013. I was here in 2014 and again in 2024. "The route of de Soto has always been uncertain, including the location of the village of Anhaica, the first winter encampment," a historical marker explains. "The place was thought to be in the vicinity of Tallahassee, but no physical evidence had ever been found." Calvin Jones' chance discovery of 16th century Spanish artifacts in 1987 settled the argument. Jones, a state archaeologist, led a team of amateurs and professionals in an excavation which recovered more than 40,000 artifacts . . . These finds provided the physical evidence of the 1539-40 winter encampment, the first confirmed De Soto site in North America." |

To enlarge these images, click on them!

|

|

After the Spanish took over Anhaica, which had been forcibly abandoned by its Apalachee natives, they were under constant attack by the Apalachees. According to the signs here, perhaps that is the reason why accounts of that portion of the expedition mostly detail those raids and fail to mention Christmas celebrations.

Yet historians believe that "the three priests who accompanied the De Soto expedition would have ensured that Christmas traditions were upheld," according to another sign titled "De Soto's Christmas in Tallahassee." |

|

The signs also explains that, "from this location the De Soto expedition traveled northward and westward making the first European contact with many native societies."

We are not heading west folks, not on this road trip. But since we are heading north, I say we should follow De Soto's route, at least through Georgia and the Carolinas? Are you coming? |

Hernando de Soto

|

|

"His exact route is unknown and certain landmarks mentioned by the scribe of the expedition remain unidentified," the marker explains. Yet it also notes that Alligator Spring, near Arlington, “has the best claims of existing springs to identification with the ‘White Spring’ (Fuente Blanca) at which Hernando de Soto and his army encamped on the night of March 17-18, 1540.”

The De Soto expedition trekked across territory that later became Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana. Their four-year, 4,000-mile hike finally lost its drive when de Soto died of fever at the banks of the Mississippi River, where he was buried in May 1542. I don't intend to follow those footsteps, lol, but I say we should keep looking for historical markers on our way north! Are you coming? |

Following the Trail of Conquistadors in Milledgeville, Ga.Some 175 miles north of Arlington, Ga., where we found a historical marker for the Hernando de Soto expedition, another Georgia town still recognizes their route. "Many scholars believe that this was the general area where the De Soto expedition visited April 3-8, 1540," says the historical marker in downtown Milledgeville, Ga.

"In May 1539 Hernando de Soto landed in Florida with over 600 people, 220 horses and mules, and a herd reserved for famine," the marker claims. "Fired by his success in Pizarro's conquest of Peru, De Soto had been granted the rights, by the King of Spain, to explore, then govern, southeastern North America." |

|

After spending the winter in the Tallahassee area, the expedition "set out on a quest for gold which eventually spanned four years and crossed portions of nine states," the marker says. While recognizing that "this tremendous effort" forever changed the lives of the Indians who were infected with old world disease or killed in battle, the marker also notes that "this was the first recorded European exploration of the interior of the Southeast" and that "over 300 members died on the expedition, including De Soto in 1542."

The marker also explains that the Indians of the Chiefdom of Altamaha "ferried the Spanish across a large river in dugout canoes" and traveled northeastward. And wouldn't you know it? That's the direction we are taking! We are not taking canoes, lol, but on this road trip we are following the trail of conquistadors! Are you coming? |

Following De Soto's Trail

|

|

Here in western North Carolina, a part of the country where four current U.S. states nearly meet — Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee — the De Soto expedition went as far northeast at the village of Joara (near present-day Morganton, N.C.), then changed course and began heading southwest across portions of Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana, until they found the Mississippi River.

Their journey took four years and 4,000 miles, wiggling across today's U.S. map from Tampa Bay to Mexico. But the expedition lost its leader and will to keep exploring when De Soto died of a fever and was buried in the Mississippi River in May of 1542. Dodging attacks by natives, the survivors made their way to Mexico, where they knew they could hook up with other Spaniards. Of some 600 who started this journey, some 300 survived. |

|

But when the expedition was here and crossed the Little Tennessee River in western North Carolina, De Soto was already leading them back in a southwestern direction.

Nevertheless, I say we should keep going north to Joara. After all, some 27 years after De Soto was there, other Spanish explorers built a fort there. Let's go! |

April 2024

De Soto's Route in TennesseeHaving already followed the path of the 1539-43 Hernando De Soto expedition, through Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina in August of 2022, for my new trip, I picked up their trace in McDonald, Tennessee.

Here you find that the expedition followed Native American paths and passed near this spot in 1540. The marker, erected by the Tennessee Historical Commission, is at the intersection of South Lee Highway (U.S. 64) and south McDonald Road. |

"From Canasoga, near Wetmore, to Chiaha, near South Pittsburg, De Soto's expedition of 1540 followed the Great War and Trading Path, which ran from northeast to southwest, passing near this spot," the markers says.

Hernando De Soto's Trail in AlabamaSouth of Chattanooga, Tennessee, across the northwest corner of Georgia, and soon after entering Alabama, heading southwest on I-59, you find a visitor's center where the first European visitors to this area are recognized. (See map). The Spanish expedition led by Hernando De Soto came through here some 67 years before British colonists came to Virginia.

"Hernando de Soto brought his 700-man army to Alabama in the fall of 1540," a two-sided historical marker explains. "This was the first major European expedition to the interior of the southeastern United States. The De Soto expedition had landed at Tampa Bay, Florida, in the spring of 1539 – 47 years after Columbus discovered America. They traveled through parts of Florida, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas before abandoning their goals of finding riches and leaving for Mexico in 1543." Over the years, anthropologists and historians have developed various hypothesis to describe the actual route taken by De Soto – but they still don't know the specific trail! "Archaeologists believe that they know the general route that De Soto followed and are trying to locate the specific towns he visited in order to verify their theories," the marker explains. An "official" route was determined by a national commission in 1939. But anthropological work has altered the route since then. In creating these makers, with very eye-catching maps, the State of Alabama adopted the trail promoted in 1988 by Dr. Charles Hudson, of the University of Georgia, and his associates. The marker even outlines "The Highway Route of the De Soto Trail," which is "intended to follow the actual trail as closely as major highways permit," and which is precisely what I'm doing on this road trip! In Alabama, the marker explains that De Soto was betrayed by Indian chief Tascalusa. "The chief, resentful of the harsh Spanish treatment of the Indians, promised De Soto supplies and bearers at one of his small towns, Mabila. But there on October 18, 1540, De Soto and his advance party were ambushed by Tascalusa after they entered the town." When De Soto called up the main body of his troops and fought an all-day battle, more than 20 Spaniards and 2,500 Indians were killed in what the marker describes as "the greatest Indian battle ever fought in America." The Spanish prevailed, but the battle was a turning point for the expedition. "De Soto discovered no gold or silver, and an unsuccessful exploration had now turned into a near-defeat with major casualties," the marker elaborates. "The expedition continued slowly on toward Mississippi. The next three years would see the discovery of the Mississippi River, the death of De Soto from fever, and the eventual retreat of some 300 survivors to Mexico." Well, this time we are driving toward Mississippi, and my Great Hispanic American History Tour is moving a lot faster. Are you coming? |

DeSoto Falls, an unexpected natural beauty in AlabamaIn my effort to follow the route taken by the Hernando De Soto expedition, by visiting monuments and historical markers that recognize he was there, I found that there are towns, counties, parks, streets, waterfalls and even caverns that bear his name, not because he was there, but because he was in that area.

For me, perhaps most impressive was DeSoto Falls, which is in DeSoto State Park, on Lookout Mountain, 8 miles northeast of Fort Payne, Alabama. When I went there, I wasn’t expecting to find such natural beauty! These 104-foot falls, the tallest in Alabama, have carved their own small canyon! The 3,502-acres, mountain terrain park, the largest in Alabama, has forests, rivers and waterfalls — the kind of turf the De Soto expedition encountered in 1539-43, as it trekked across territory that now covers 10 American states. The park was established in 1935 and named after the Spanish explorer when it was dedicated in 1939. Check out the two short videos below: |

|

Historic (Hispanic) Childersburg: The Oldest City in America?I saw it called Cosa, Coosa and Coca, but nevertheless it was the Native American Village visited by the Hernando De Soto expedition in 1540 and now known as Childersburg, Alabama.

De Soto's visit is still notable here, in monuments and historical markers that help citizens remember the town's Indian and Spanish roots. In fact, because it was visited by De Soto in 1540, some 25 years before the Spanish established a colony in St. Augustine, Fl., Childersburg city officials have been known to call it "The Oldest City in America." Of course, there is a huge difference between visiting an Indian village in 1540 and establishing a Spanish colony in 1565. In my book, that still makes St. Augustine the oldest, continuously-inhabited European city in the U.S.A., beating British Jamestown, Va. by 42 years. Nevertheless, Childersburg, incorporated in 1889 and home to close to 5,00 residents, proudly claims its Indian and Spanish heritage. “Childersburg traces its heritage to the Coosa Indian village located in the area,"notes one of the historical markers on the corner of First Street SW (Alabama-76) and Sixth Avenue SW, near the Childersburg police headquarters. "DeSoto, accompanied by 600 men, began his March across North America in June 1539. Traveling from Tampa Bay, Florida, northward through what became the Southeastern United States, DeSoto’s expedition began searching for riches.” After trekking north through present-day Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and reaching as far north as present-day North Carolina and Tennessee, the expedition was heading back southward when it reached present-day Alabama. “Upon entering the area that would become Alabama, DeSoto and his men marched southward along the Tennessee River,” the historical marker explains. “On July 16, 1540, the army of Spaniards entered the town of Coca (Coosa) located on the east bank of the river between two creeks, now known as Talladega and Tallaseehatchee.” That’s the current location of Childersburg. The marker explains that DeSoto was greeted by the chief of the Coosas. “For approximately a month, these invaders enjoyed the hospitality of the chief and his tribe, receiving an offer of land to establish a Spanish colony. After offering reasons for not accepting, the Spaniards departed Coosa in August 1540, leaving behind members of the expedition.” Another marker notes that, “Beginning with men left by DeSoto and continuing during a period of approximately 250 years, explorers, conquistadors, traders, and pioneer settlers penetrated the vicinity and occupied the area that is today known as Childersburg, Alabama.” As for the "men left by DeSoto," local folklore says that least one Spanish soldier, who was apparently too ill to travel, remained behind to live with the natives. But to follow De Soto's trail, we must now head northwest, into northern Mississippi. Are you coming? |

My Great Hispanic American History Tour Goes to Mississippi! Are you coming?Are you following my new road trip? We're just entering northeast Mississippi as I keep tracing the route taken by the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1539-43. If you have followed my other cross-country road trips, and this website, you know that my goal is to create a "Bucket List of Places, Ideas and Historical Evidence to Reconnect Americans with their Hispanic Roots."

But I need your help in divulging this information! Please SHARE my history postings with friends who would be interested in learning more about our Hispanic history in what is now the U.S.A. My goal is huge, and I cannot achieve it alone. ™Me ayudas? |

Centuries before Elvis was born here, Hernando explored this areaTupelo, Mississippi — Some 395 years before Elvis Presley was born here and put this small town on the map, Spanish explorers were already drawing maps of this area.

Their presence is recognized at a prominent corner on Main and Church Streets in downtown Tupelo, where a small monument commemorates "Hernando De Soto and his men, who spent the winter of 1540-1541 in North East Mississippi prior to his discovery of the Mississippi River." Tupelo is a citi of some 38,000 people. The De Soto monument is less known than Elvis' 1935 birthplace, now a small museum. But it stands as one more significant marker documenting the journey of hundreds of Spanish explorers across the Southwest of the present-day U.S.A. That was some 67 years before British colonists came to Virginia and some 264 years before Lewis and Clark embarked on their much more celebrated expedition. After heading southwest from the Carolinas and Tennessee, and after crossing present-day northern Alabama, the expedition pivoted toward the northwest when it reached present-day Mississippi. (See map). My Great Hispanic American History Tour is going that way. Are you coming? |

A historic scare!There I was, excited to be on yet one more of my Hispanic history research road trips, this time following the trail of the 1539-1543 Hernando de Soto expedition across the Southeast, and it wasn't my car that was breaking down. lol

When I got up one morning, in Tupelo, Mississippi, ready to grab the wheel for another long drive, I realized that my fingertips were numb. Concerned about what could be the cause, and realizing that tornado warnings were going to keep me off the road anyway, I paid a visit to the North Mississippi Medical Center, a huge and impressive hospital recommended by my hotel clerk. I must admit, driving myself to ER in a hospital several states away from home was a little unnerving, especially after the medial staff there took my condition very seriously. Their questions made me believe that they thought I had suffered a stroke! "But I'm following De Soto's trail and my next stop is supposed to be in a town called Hernando in a county called DeSoto," I kept telling everyone who would listen. I kept trying to add some humor to the situation as I was getting rolled on a stretcher from one medical exam to another. "I can't stop now!" I kept saying. "I LIVE FOR THIS!" They must have thought I was losing my mind. lol But in the end, I think they realized that I'm still somewhat sane. lol After a very long day undergoing every conceivable medical test they could think of, a group my new history students came to my room to give me the news that all my test were negative and, thank God, they were giving me a green light to go on with my journey. They told me the numbing of my fingers was probably from the tension of grabbing the wheel and driving too many consecutive hours and suggested I consider a slower pace, a maximum of four to five hours per day. I did, and it worked! "But before you leave, you must do me a favor," said one doctor in such a serious tone that I expected some bad news after all. He pointed to the tray of hospital food that had just been brought into my room and said, "Please don't eat this. Go get yourself a decent meal." I asked for "the best Mexican restaurant in Tupelo" and he gave me a prescription: "Cantina del Sol," he said without hesitation. So, I don't know whether it was the relief of knowing that the threat of tornados had passed, or that all my hospital tests came back negative, or of being discharged by a doctor with a great sense of humor, but Cantina del Sol was exceptional! |

A town named Hernando

|

|

To see De Soto's great discovery and burial, come to court!If you know anything about Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto, you know that he discovered the Mississippi River and that he was eventually buried in its waters. But unless you have visited the county courthouse of DeSoto, Mississippi, your mind probably does not register the images of those historic events.

This is where beautiful canvas murals illustrate those moments and let you see what you had only read. In "Hernando DeSoto Discovers the Mississippi River May 1541," you see the moment when a Native American guide points toward the Mississippi River, and De Soto and his men become the first Europeans to see it. "De Soto was eager to continue westward in search of gold and glory," says the small sign accompanying the mural. "To avoid attack by bands of Southeastern Indians patrolling the river, De Soto and his men crossed the Mississippi at night, guided by the light of a full moon." In a mural called "DeSoto's Burial in Mississippi River," you see the moonlight ceremony before his body was interned on the western banks of the river, either in present-day Arkansas or Louisiana. "Because the Soto had portrayed himself as an immoral son of God to gain control over southeastern Indians, his men feared attacks if De Soto's death should become known," a sign explains. "Instead of digging a gravesite, De Soto’s men wrapped his body with weights and sank it in the Mississippi River during the night . . . The exact location of De Soto’s burial is not known, and his remains have never been found."

While a sign here explain that "diseases introduced by Europeans killed a large portion of the native population," another sign notes that De Soto was 42 when he died of "a fever." So, clearly European deseases were also killing European explorers in the Americas. In "De Soto's Embarkation 1538," you see a mural illustrating the expedition disembarking from Havana on its way to Florida. And in "DeSoto guided through the forests," you see how the expedition was guided by Native Americans. Although there are nine murals in the courthouse, luckily for me, the four illustrating the De Soto expedition are in the building's rotunda and readily available to the public. The other paintings, in less-accessible courtrooms, depict the expeditions led by French-Canadian explorers Louis Joliet, Jacques Marquette and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. The nine murals, some of the largest ever painted by American muralist Newton Alonzo Wells, were first commissioned for the old Gayoso Hotel in Memphis, where they hung from 1903 to 1948. According to a historical marker here, when the hotel was renovated into Goldsmith's Department Store in 1948, the City of Hernando convinced owner Fred Goldsmith to donate the murals to the city. After the town raised $5,000 to restore the murals, they were installed in the DeSoto County Courthouse in 1953. Now they have a combined appraised value of more than $1 million, the maker says. At my next stop, I went to a museum and ended up at the site of a huge historic event. Stay tuned. |

To enlarge these photos, click on them!

|

'Hernando De Soto stood here,' says Mississippi historianAfter visiting the DeSoto County Courthouse in Hernando, Mis., and seeing its wealth of art and history about Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto, for whom this city and county are named, it was hard to imagine a more impressive site for me to visit. But Hernando has a small museum and I could not leave town without stopping there first.

Yet shortly after arriving at the DeSoto County Museum, and describing my journey to the only person working there, Robert Long III gave me a pensive look for a few seconds and then shocked me. "I'm tracing De Soto's route," I told him. "I'm going to close the museum," he said. "Whaaat?" I asked. "Why?" "Because I'm going to take you to the spot where De Soto stood when he discovered the Mississippi River," he said. "And so," I said, cracking a huge smile, "what are we waiting for?" He took his car, I followed him in mine, and we drove for about a half hour out of town. When we finally stopped, northwest of Hernando, we were standing on a bluff overlooking a huge area where a body of water once stood, and where we could see the Mississippi in the distance. "This is it," he said. This is where it happened. De Soto stood here." He explained that the river once ran much closer to the bluff where we were standing because several centuries ago it was wider and unrestrained by development, making the historic bluff described by De Soto's explorers much more difficult to locate by archaeologists and historians. Yet, after many years of research, speculation and debate, Long says local historians now agree on the site he was showing me. De Soto saw the river from a distance then and we were seeing it from a much farther distance now, but it was the river that moved father away, said Long who is the museum's head curator and a presbyterian minister in Hernando. It took us another few minutes to drive to the river banks, at (wouldn't you know it?) the Hernando De Soto River Park. "Under the flag of Spain, Hernando De Soto's nine ships and 650 men landed in Tampa Bay in 1539," notes a historical marker at the park. "Hoping to find gold . . . they traveled to present-day North Carolina, then headed south and west, visiting northeast Mississippi before arriving at this point on May 8 1541." (See map). The park marker explains that for centuries before the Spanish arrived here, Indians lived, farmed, hunted, and build mounds along the river’s banks. It says that De Soto's men were the first documented Europeans to encounter the Indians and to cross the Mississippi. “De Soto's men had heard tales of this river, but they were stunned by his sheer size," the marker says. "Over the years the path of the river has changed, making it impossible to document the exact location of his of his river crossing." Also unknown is the spot where De Soto was buried, especially since his body was wrapped in sand-weighted blankets and sank in the river. He died on May 21, 1542, and his secret nighttime river burial was because his men feared attacks if Indians should learn of his passing. “After De Soto’s death, his army set out to find a land route through Texas to Mexico, but dwindling supplies forced them to turn back," the maker explains. "In June 1543 they set out down the Mississippi River. They sailed into the Gulf of Mexico six weeks later. No gold or other riches had been found.” Since the river now serves as the borderline between Mississippi and Arkansas, by crossing the river, the expedition began its exploration of present-day Arkansas. And so will we! But it's much easier nowadays. We can do it over a bridge. Can you guess what that bridge is called? |

|

Almost 5 centuries later,

|

|

De Soto reaches Arkansas, finds maize instead of gold!When the Hernando De Soto expedition crossed the Mississippi River and arrived in the present-day State of Arkansas in 1541, his explorers were already terribly disappointed. They had already trekked on foot for more than two years through several present-day American states and had not achieved their goal.

"The expedition’s goal was to find a North American kingdom of gold on the scale of the Aztecs of Mexico, who had been conquered by the Spanish 20 years earlier," explains a historial marker I found in Marion, AR., as I retrace the path of the De Soto expedition, which began in Tampa Bay in 1539. The marker notes that, "They found not cities of gold, but numerous well-populated villages supported by vast fields of maize." They were "the first Europeans to enter Arkansas," and to find Mississippian culture! "The Spaniards had entered the Mississippian Period, world noted for their mound building and hierarchical political systems," the marker explains. "Powerful chiefs controlled several villages that provided tribute to them." Yet more than a century later, by the time French explorers became the next Europeans to write down their observation about this area in 1673, "the flourishing Mississippian towns were gone," the marker says. "A variety of explanations have been offered to account for this disappearance, including European diseases and severe, long-lasting drought in the 1500s. Both undoubtedly played roles." While most historical markers celebrate accomplishments, every so often you find one clearly influenced by that centuries-old detrimental propaganda campaign against Spaniards known as The Black Legend. Sometimes, while recognizing Spanish accomplishments, some historical markers go out of their way to take a jab at De Soto and his men. "For the next two years, the Spaniards explored through Arkansas with a large number of captive Indians," the marker jabs. "They killed numerous natives, gorge themselves on native food stores, and disrupted the region's political systems . . ." During this trip, I have seen more balanced and less prejudicial historical markers, the kind that explain that the natives also killed numerous Spaniards. But not this one. This one is a bit misleading. Unlike most others, this bizarre recognition of the expedition has a lot more Black Legend bull crap than normal. As one travels across the Southeast, retracing De Soto's expedition of almost five centuries ago, different interpretations of this story become obvious from state to state. You see how local historians recall De Soto slightly differently. After seeing many of these signs, contradictions and misinformation is easily be detected. Sometimes you feel like the information needs to be updated, and even images need to be redrawn. For example, when I saw the marker in Marion, I noticed that it features a black and white rendition of "Discovery of the Mississippi by De Soto," a well-known painting (see color photo) by William Henry Powell, especially because it hangs in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. Yet according to another marker I saw in Mississippi, Powell's depiction of Southeastern Indians living in tepees is totally off base. "These Indians actually lived in wooden buildings with mud-daub walls and thatched roofs," says the Mississippi marker. In fact, those wooden building are depicted in a second image in the Marion marker, making the contrast between the accurate and inaccurate native living quarters easily detectable. (See photos). I'm hoping that south and west of Marion, other Arkansas markers will really celebrate the accomplishments of the De Soto expedition. But that will have to wait for my next trip. For now, I'm following the path of the Mississippi River heading south, all the way to New Orleans (see map), and stopping at other De Soto makers along the way. Are you coming? |

Road markers take you back

|

Beautiful parkway

|

Check out this Natchez Trace Parkway video by the National Park Service:

|