78. A Tour of Our Extraordinarily

|

|

Latino issues may be ignored in Congress — we know that! — but it's not because our elected officials don't see constant reminders of our Hispanic heritage. In the U.S. Capitol, our history is constantly on display. You would have to be blind not to see it.

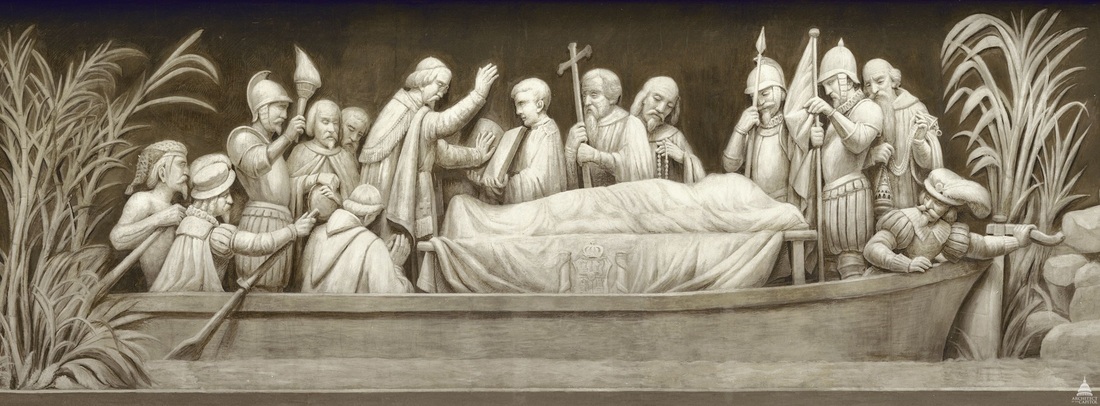

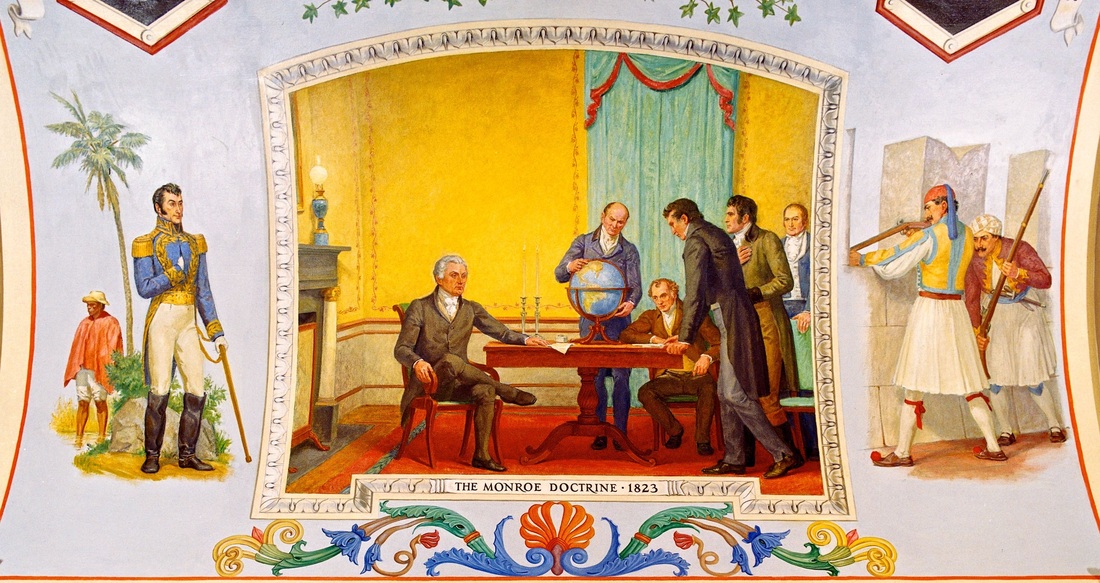

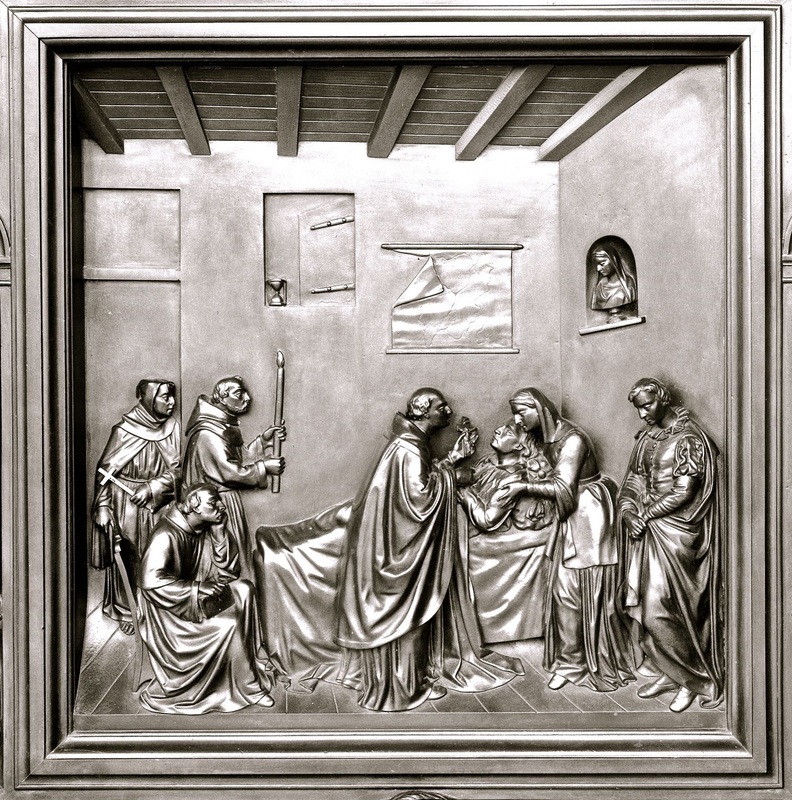

When our conservative legislators discriminate against Hispanic immigrants — as if others were more entitled — you have to wonder whether they ever look up at the imposing painting in the Capitol's rotunda of De Soto at the Mississippi in 1541, almost 80 years before the Mayflower landed on Plymouth Rock. They should know better! But if you are a visitor, enthralled by the beauty and history of the U.S. Capitol — walking through corridors of art that could compete with the world's finest museums — you may not immediately notice how much Hispanic heritage is on display there. Of course, we are on the Great Hispanic American History Tour. I went looking for our roots, and I was pleasantly surprised. Capitol paintings, sculptures and other artworks take you back in time to some of the most important moments in Hispanic American history. Even before a portrait of Spanish Gen. Bernardo de Galvez was hung in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee room in December (the subject of my most recent column), the U.S. Capitol already was one of those rare institutions where Latinos could see their heritage well-represented. It took 231 years for Congress to fulfill its promise to hang up a portrait recognizing Galvez as a hero of the American Revolution, but in fact, he became one of many other Hispanics already artistically recognized in the halls of the Capitol. In the House of Representatives, there is a marble relief of Alfonso X (1221-84), aka Alfonso the Wise, who was king of Leon and Castile and is recognized for establishing the basis for Spanish jurisprudence. There are portraits of former Reps. Eligio "Kika" de la Garza and Henry B. Gonzalez of Texas. And there is a painting of a Spanish mission, recognizing the early settlements and the missionaries who laid the foundation for many American cities. In one of the Capitol's corridors, there is a painting called "The First Four Settlements in America," clearly showing that St. Augustine (1565) was established long before Jamestown (1607), Plymouth (1620) and Savannah (1733). In another corridor, you see the image of South American liberator Simon Bolivar as former U.S. President James Monroe discusses the Monroe Doctrine, which protected the newly liberated Latin American nations from re-intervention by European powers. Bartolome de las Casas, the 16th-century "Protector of the Indians," is honored by another painting in a corridor in the Senate wing. And yet another painting in the Senate wing depicts "Columbus and the Indian Maiden." In National Statuary Hall and Emancipation Hall, where state-donated statues recognize prominent Americans, you'll find impressive bronze statues of Arizona's Father Eusebio Kino, California's Father Junipero Serra and New Mexico's Sen. Dennis Chavez. Kino (1645-1711) established missions in what is now Sonora, Mexico, and southern Arizona. He was the subject of this column when the Great Hispanic American History Tour followed part of his trail last summer. Serra (1713-84) established California missions from San Diego to San Francisco. Chavez (1888-1962) championed the rights of Latinos and Native Americans. In the rotunda's "Frieze of American History," a circular panorama depicting 19 significant scenes from American history, six of them involve Latinos. When you stand in the middle of that amazing rotunda, as you swivel 360 degrees to admire the entire frieze, you see Hispanic roots well-painted inside the Capitol's dome. That circular band of paintings depicts six immensely significant moments from Hispanic American history: —Columbus disembarking from the Santa Maria and being greeted by Native Americans in 1492. —Cortes entering an Aztec temple and meeting with emperor Montezuma II in 1519. —The Pizarro expedition trekking through the South American jungle in search of the mythical land of gold known as El Dorado, before conquering the Inca capital in Cuzco, Peru, in 1533. —The 1542 nighttime burial of De Soto in the Mississippi River. —The U.S. Army entering Mexico City during the Mexican-American War in 1847. —A U.S. naval gun crew "in the course of helping Cuba win independence from Spain" during the Spanish-American War in 1898. As if all that weren't enough to fill a small Hispanic museum, at the Capitol's main entrance stand the imposing 17-foot-high and 20,000-pound Columbus Doors, a bronze sculpture depicting nine significant scenes from Columbus' life — from the moment he stood before the Council of Salamanca in 1487 to his deathbed in Valladolid, Spain, in 1506. Designed by American sculptor Randolph Rogers, these doors are a history lesson. On the website of the architect of the Capitol, who oversees the treasures of the Capitol and the Supreme Court, there is an impressive page listing the "art featuring Hispanic culture" (http://www.aoc.gov/capitol-hill/art-featuring-hispanic-culture), with links to photographs and the history of the artworks and the artists who created them. It also recognizes the four Hispanic artists — Marisol Escobar, Henrique Medina, Francisco Pausas and Jesse Trevino — who have created other works of art in the Capitol. Well done! If you want to continue touring our remarkably Hispanic U.S. Capitol, even before you go there to see it, the architect of the Capitol's website is a great source of information — and Hispanic pride! But the Great Hispanic American History Tour has to move on. In our next chapter, we'll go exploring the streets of our nation's capital, where — perhaps distracted by so many major attractions — sometimes we fail to see our well-represented Hispanic heritage. COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM |

|

|

|

Please share this article with your friends on social media: