105. Santa Barbara:

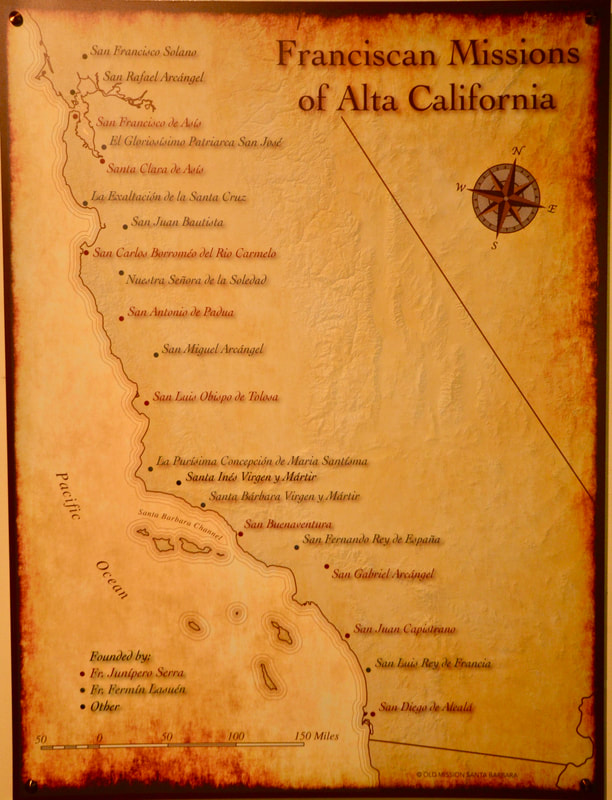

The Queen of the Spanish Missions

|

By Miguel Pérez

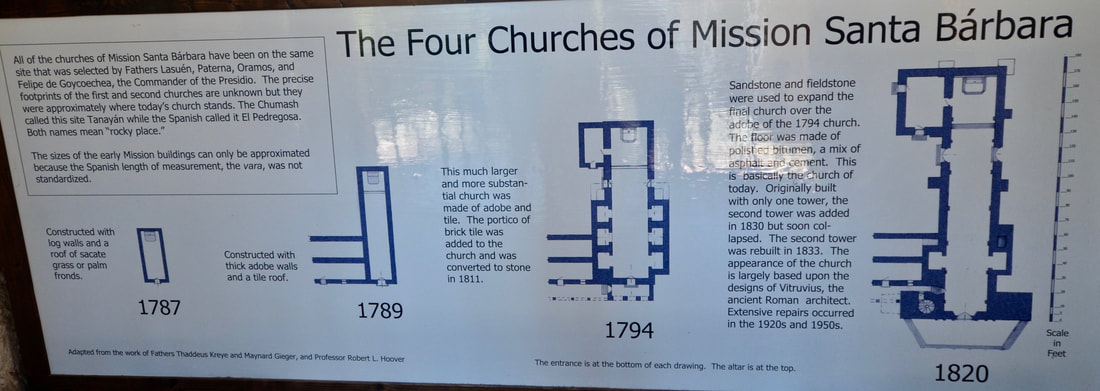

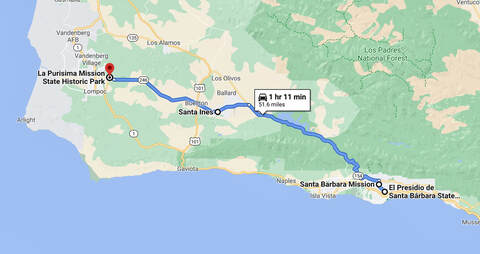

When you arrive, you feel like you've entered a photographer's paradise. Everywhere you look, you feel like you should take a picture! Established by Spanish Franciscans in 1786 and having undergone several reconstructions, Mission Santa Barbara is still recognized as The Queen of the Missions, "because of her majestic beauty." And the title is appropriate. This Mission features a "Sacred Garden," a church, a cemetery and a museum displaying original objects and art treasures from the Early California Mission Era. And it's all beautiful. You don't want to leave! Dedicated on the Feast of Saint Barbara on December 4, 1786, this mission shares the distinction (along with the 1782 Presidio Real de Santa Barbara) of being considered the birthplace the city and county now called Santa Barbara, California. The mission was dedicated by Padre Fermín Lasuén, who had succeeded Padre Junípeo Serra as president of the Franciscan Missions of California after Serra died in 1784. Serra established the first nine California missions, and he was there to bless the foundation of the Santa Barbara Presidio in 1782. Lasuén established the following nine missions, starting with Mission Santa Barbara, which is the tenth of the 21 California Missions founded by the Franciscans. Padres Antonio Paterna and Cristóbal Oramas were the first two Franciscan missionaries assigned by Lasuén to build the Santa Barbara Mission community. Four different Mission Chapels, each larger than the previous one, were built here between 1787 and 1820. The third one was destroyed by an earthquake in 1812 and the towers of the fourth one were considerably damaged by another earthquake in 1925 and rebuilt in 1927. However, the interior of the church remains the same since 1820! As you tour this mission, you learn that it was not only the missionaries who taught and trained the California natives, but highly trained artisans who were brought in temporarily, just to teach them skills and crafts that would change their lives. You learn that much of the growth of the Santa Barbara Mission is attributed to some 20 artisans who came as visiting contract workers and trainers between 1792 and 1795. According to exhibits at the Mission museum, Father Lasuén "emphasized training baptized native peoples at missions such as this one in Santa Barbara to be carpenters, blacksmiths, stonecutters, masons, weavers, tailors and millers, which allowed the missions to be more independent of the presidios and towns. He invited artisans from New Spain to temporarily migrate to the California missions where they taught baptized native peoples their craft or skill, and in turn the newly trained would pass on their skills to others." The exhibit explains that, "the growth of an artisan class at the missions had an impact on the individuals as well as the missions. Baptized native peoples had acquired skills that were highly desired throughout colonial society, and these newly developed skills gave the artisans a higher status." Another way to gain social status was by joining a mission choir. Natives who were talented singers and those who learned how to build and play musical instruments usually acquired status is the social hierarchy of the community. "Native peoples in the choir often possessed a greater familiarity with the Spanish language than other native peoples at the missions, which facilitated their interaction with the Californios or colonists," another exhibit explains. Mind you, relations between the Chumash natives and the Spanish soldiers was not always great, and the Franciscan friars were usually caught in the middle. Relations were usually strained when the Spanish presidios (forts) failed to receive adequate support from New Spain (Mexico) and had to depend on the missions for supplies and Chumash labor. There was also some Chumash resistance to the Catholic religion and Spanish culture that was being imposed on them, culminating in 1824, when a group of naives participated in a revolt and later surrendered. "The Friars remained true to their intent to protect the Chumash from Spanish exploitation and at least one remained with the Indians throughout the revolt ministering to them," an exhibit explains. "The missionaries also played a large role in negotiating their surrender." Okay. But what about today? "Chumash today are reviving aspects of their ancestral culture and religious traditions," the exhibit explains. "At the same time, many remain part of the Catholic Church." And so does the work of their ancestors! The work of Chumash artisans can be seen throughout the Mission church and museum. Although the Mexican government secularized the 21 California Missions and sold the mission lands in 1834-36, Santa Barbara holds the distinction of being the only mission that continued to operate while the others had to close, at least temporarily. A museum exhibit explains that, "Due to a variety of circumstances, Mission Santa Barbara did not close and has continued as a Franciscan church and community even to this day." During secularization, artifacts from other missions were mostly lost. But because the friars were able to remain in Santa Barbara, mission treasures were not only preserved here but, according to an exhibit here, some "art, artifacts and documents housed at other Missions made their way here." From the very beginning of the City of Santa Barbara, while the mission fathers began the slow work of converting the Chumash natives to Christianity, and teaching them how to build their own Spanish-style village, a pueblo grew around the Presidio, populated by new settlers and the soldiers own families. And thus what began as a fort, surrounded by a small cluster of adobe tenements, and a nearby Franciscan mission built by Chumash Native Americans, grew up to become a major metropolis! |

En Español:

|