58. There Was Compassion

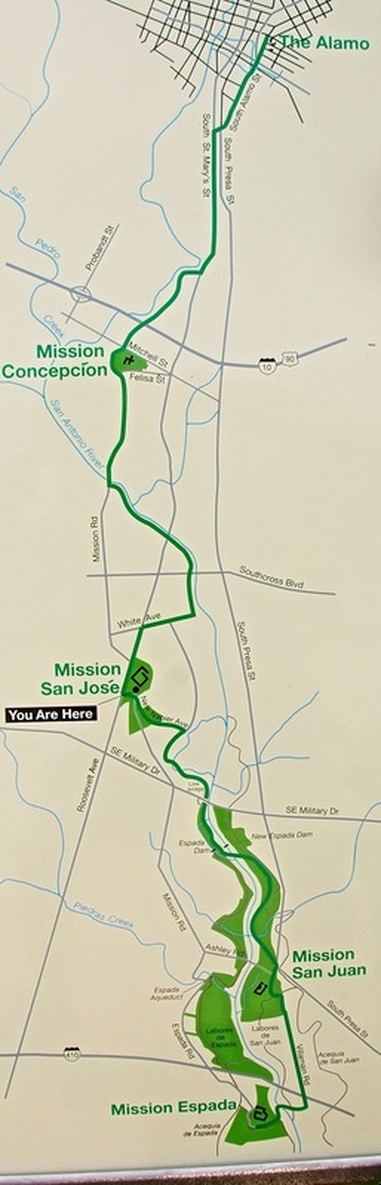

On the Spanish Mission Trail

|

By Miguel Pérez

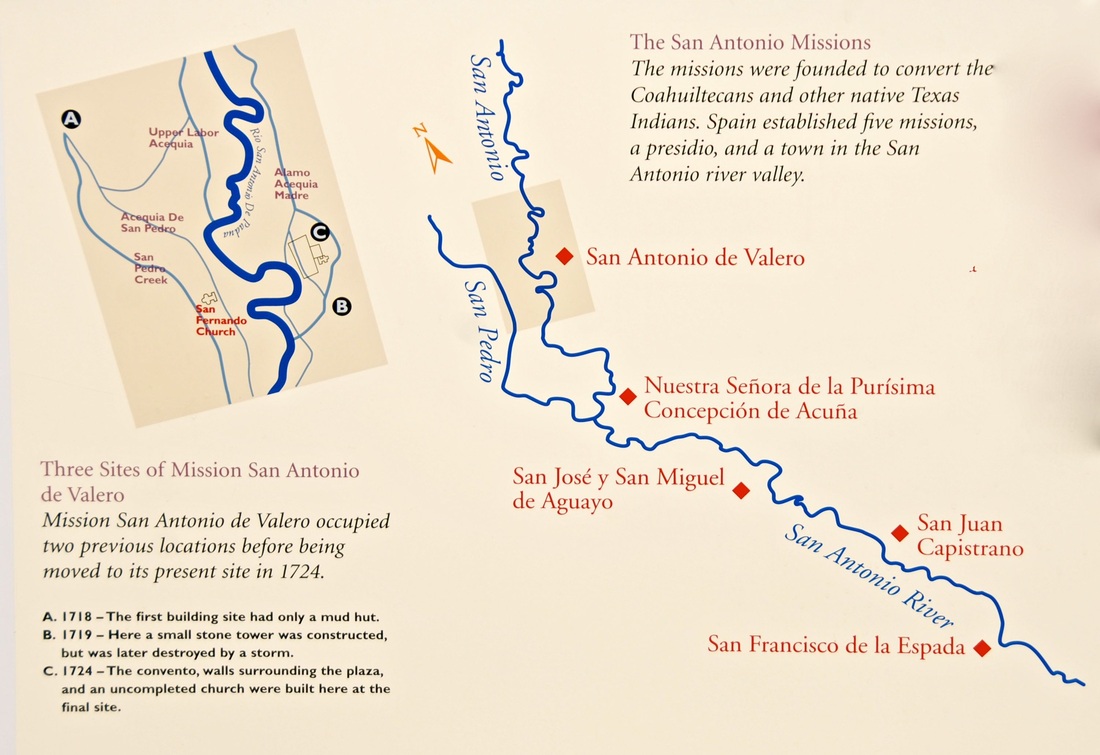

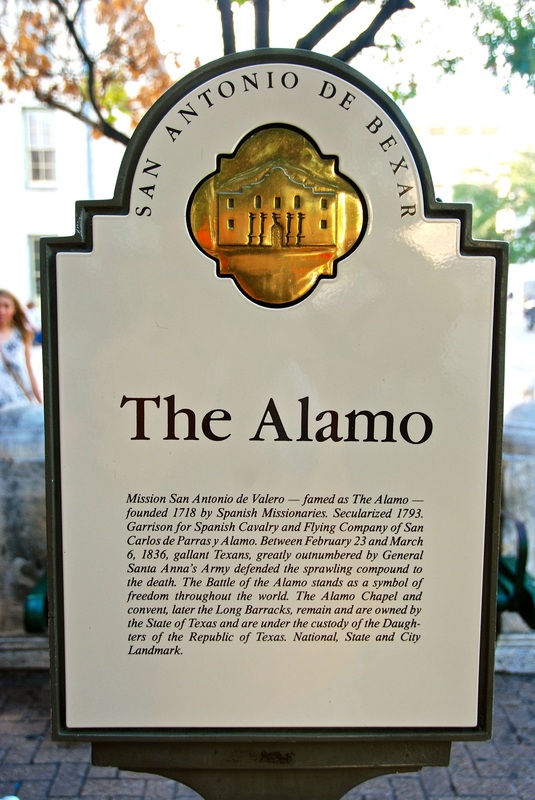

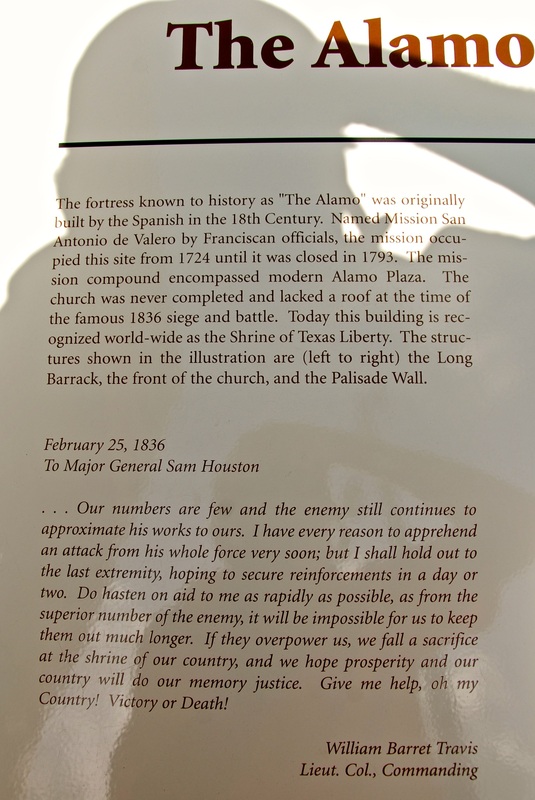

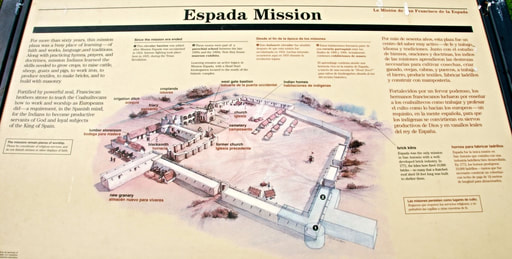

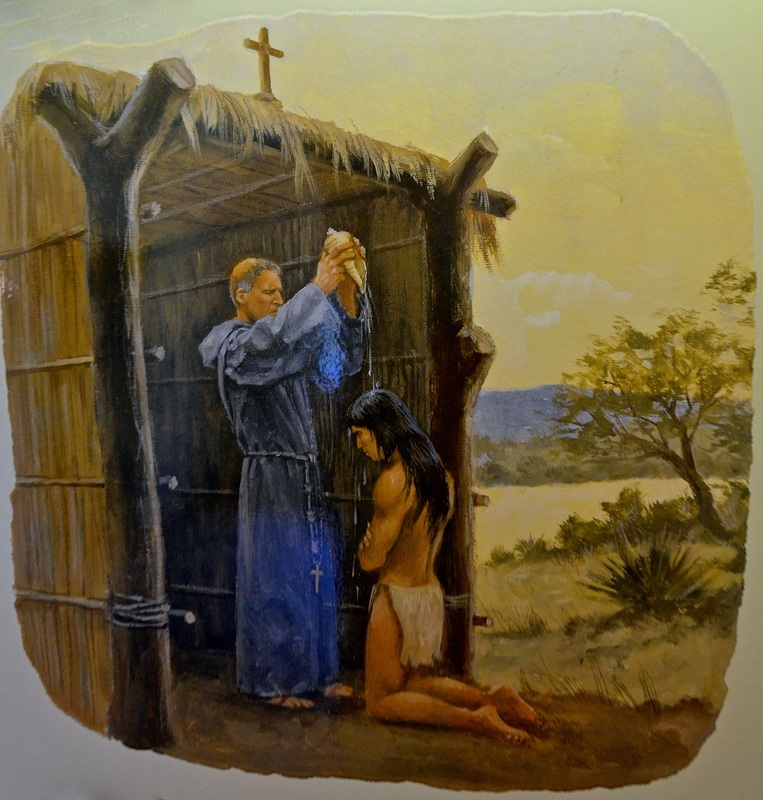

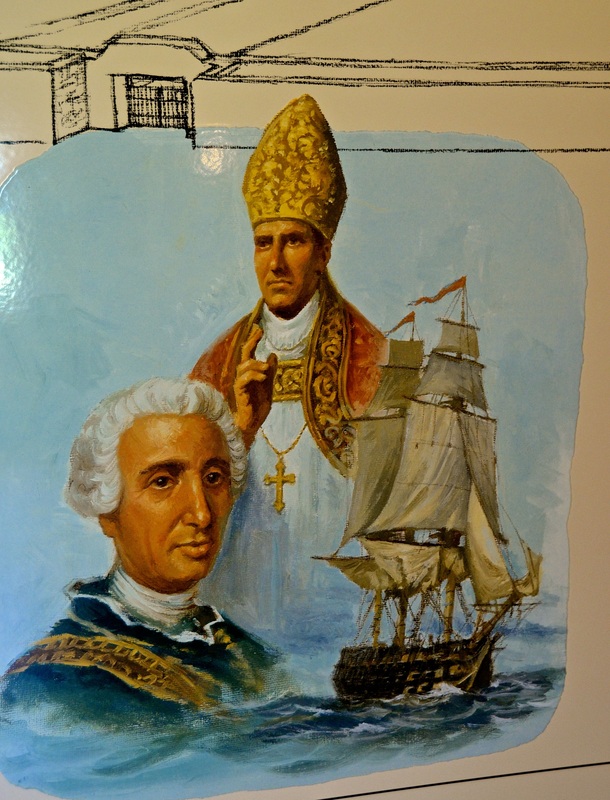

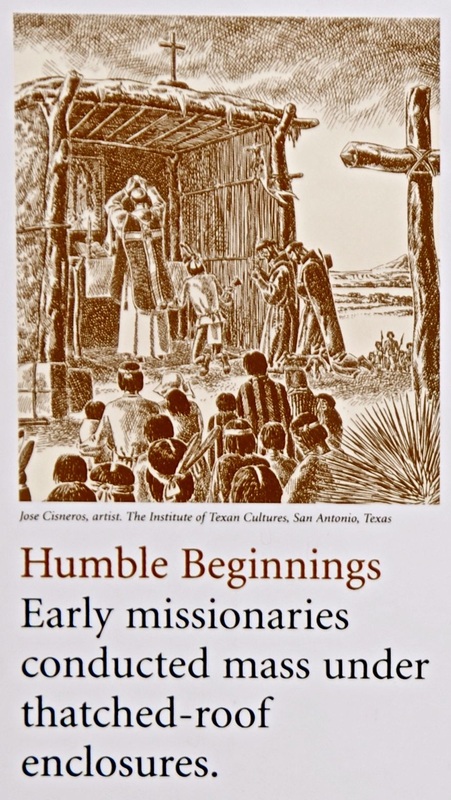

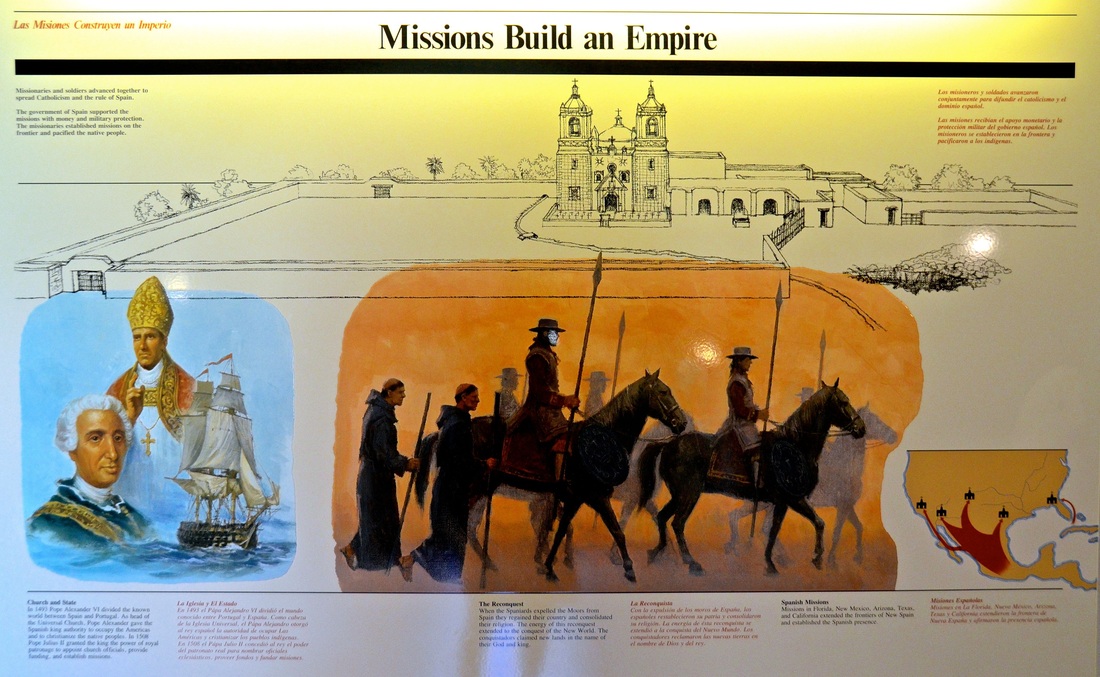

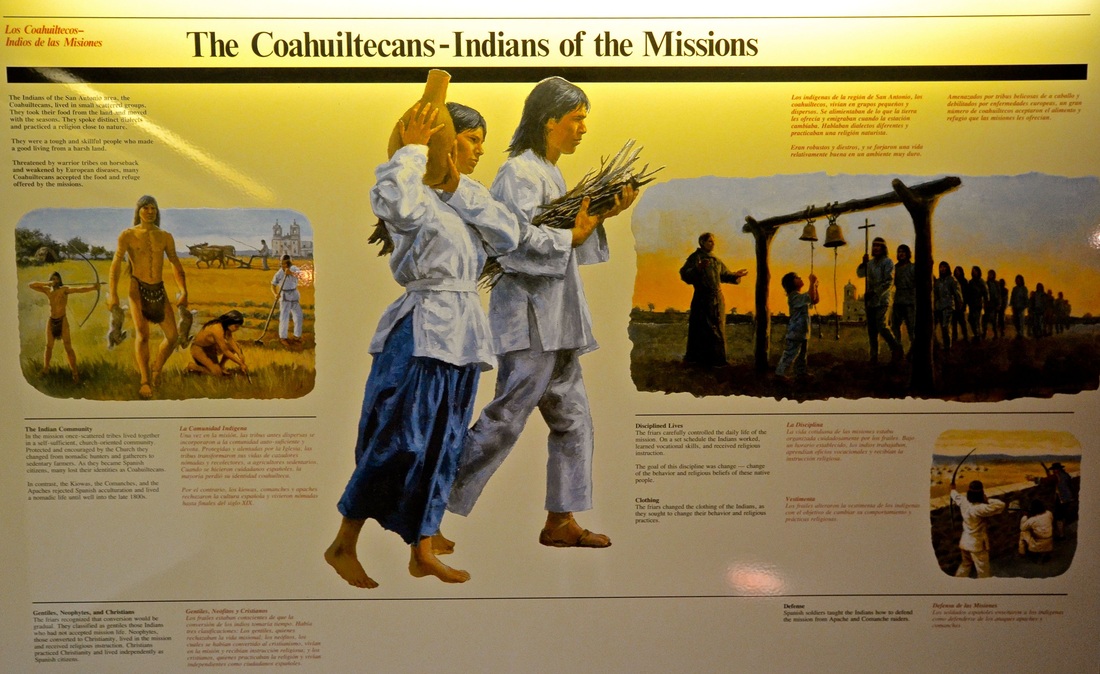

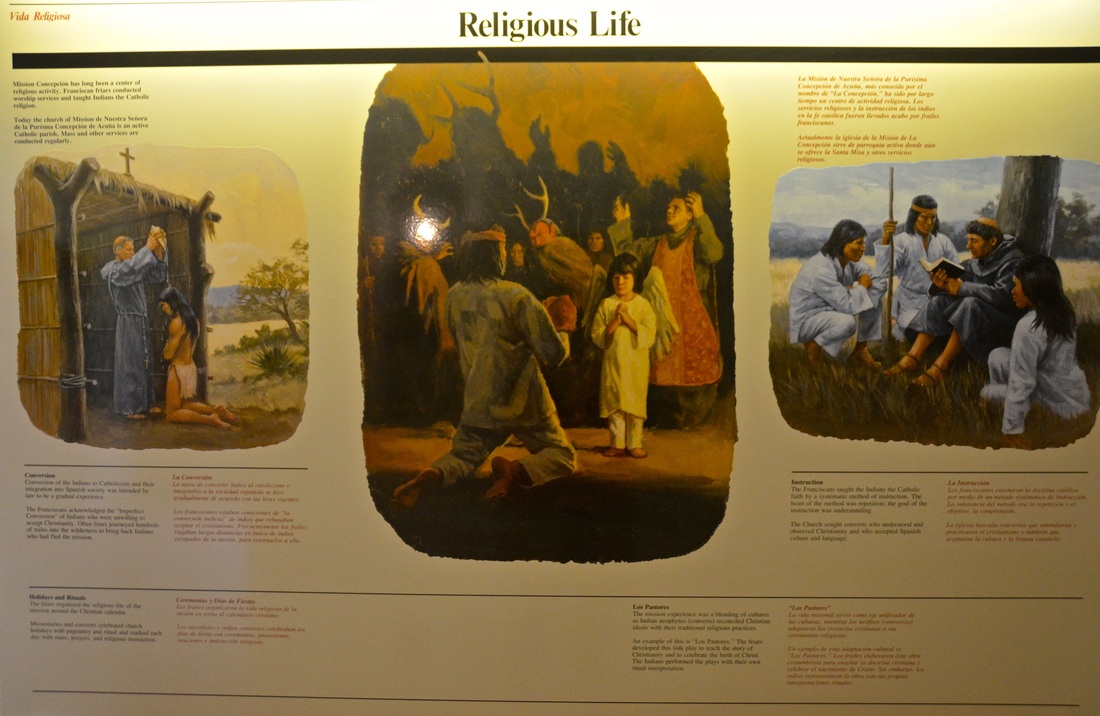

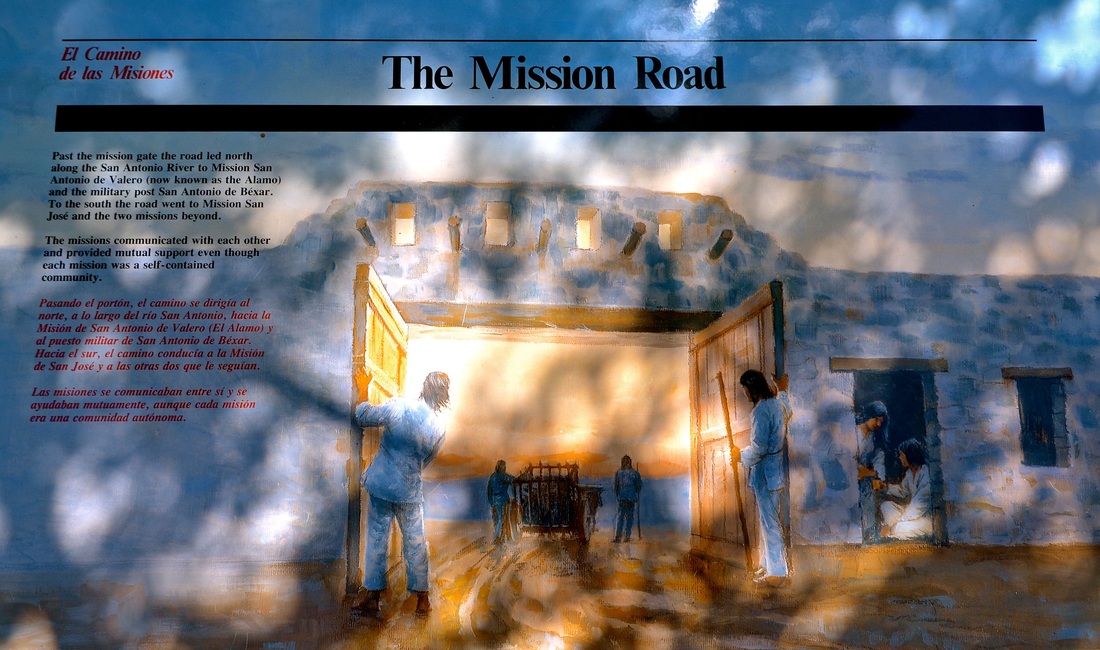

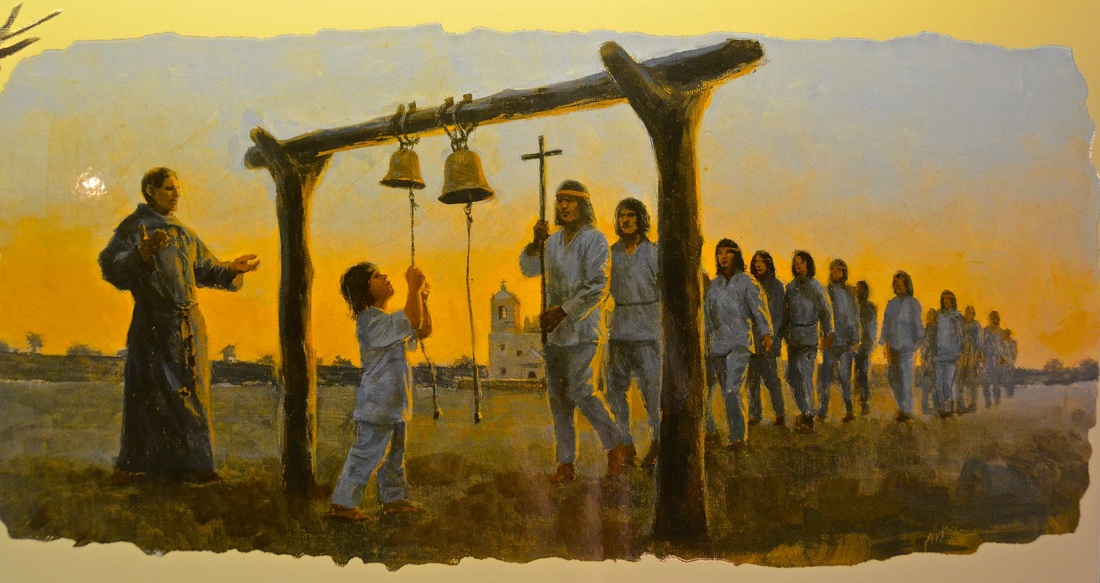

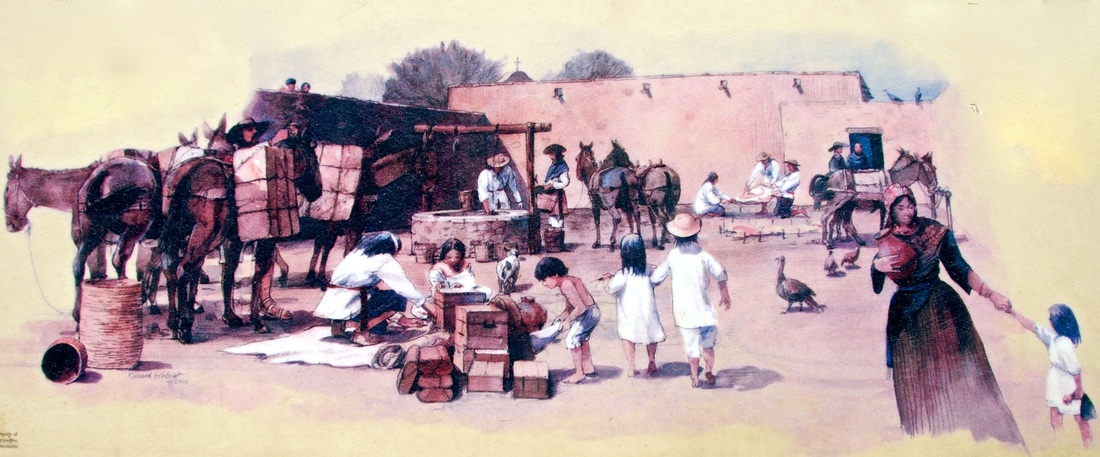

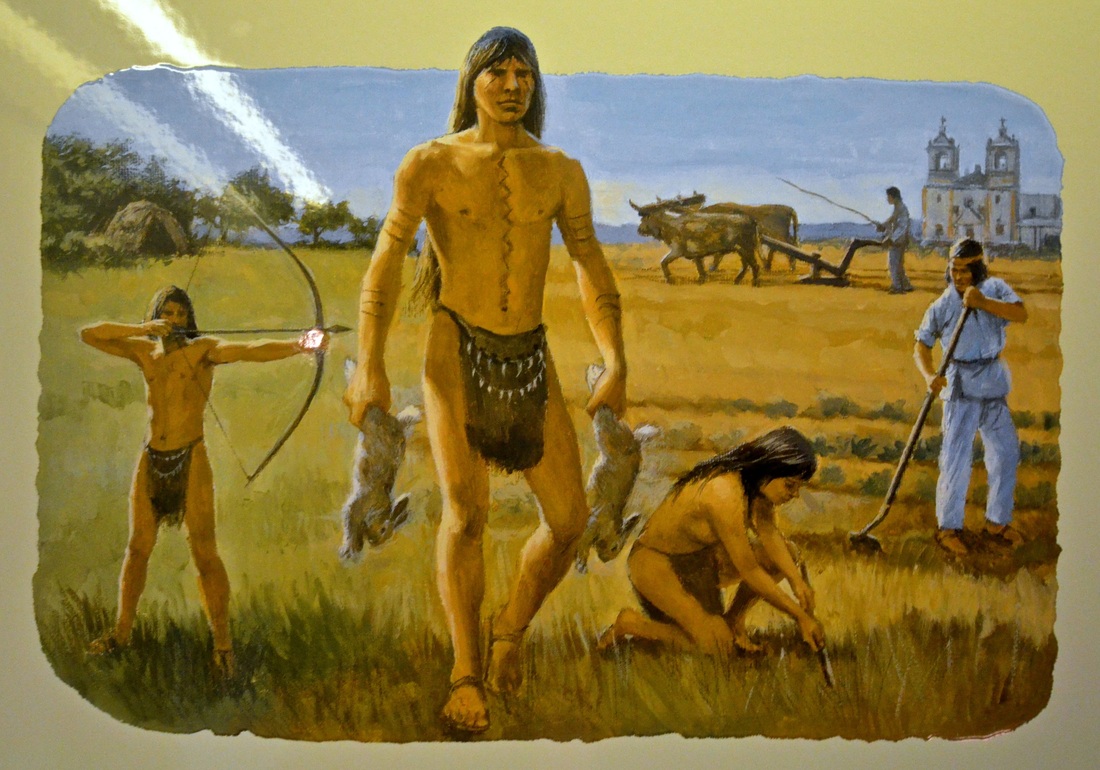

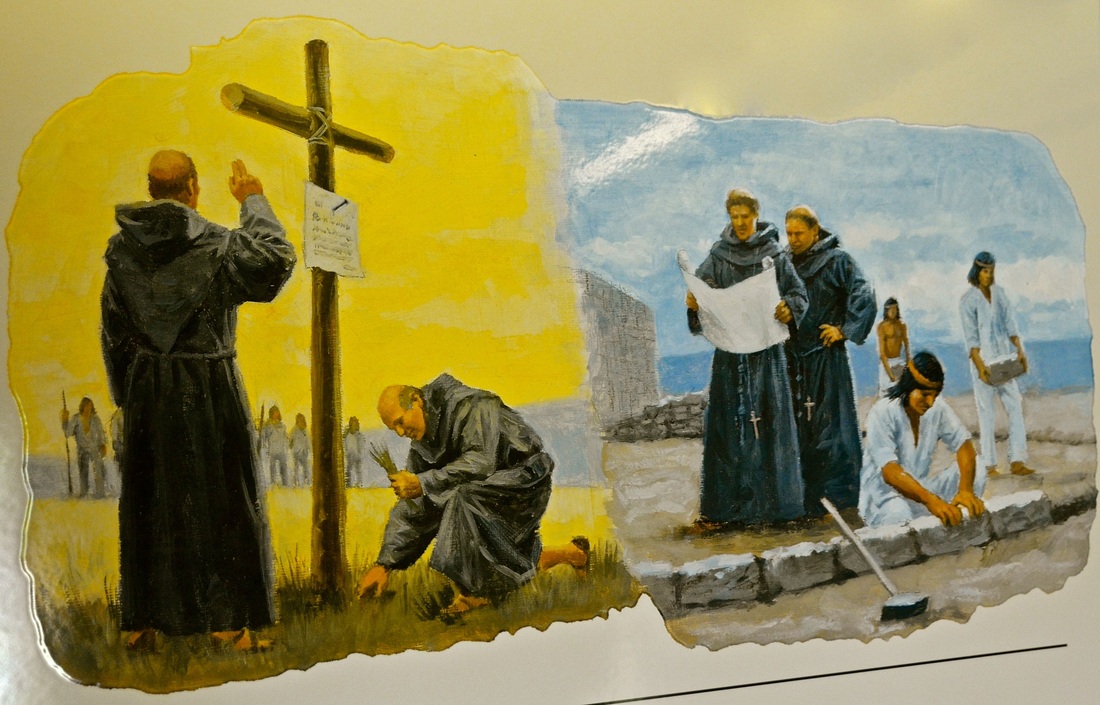

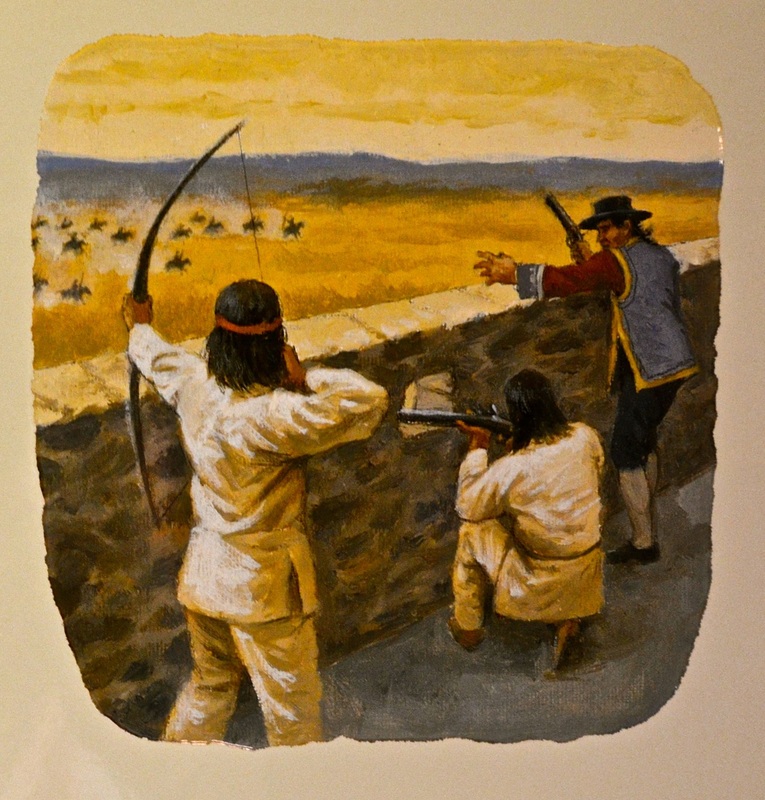

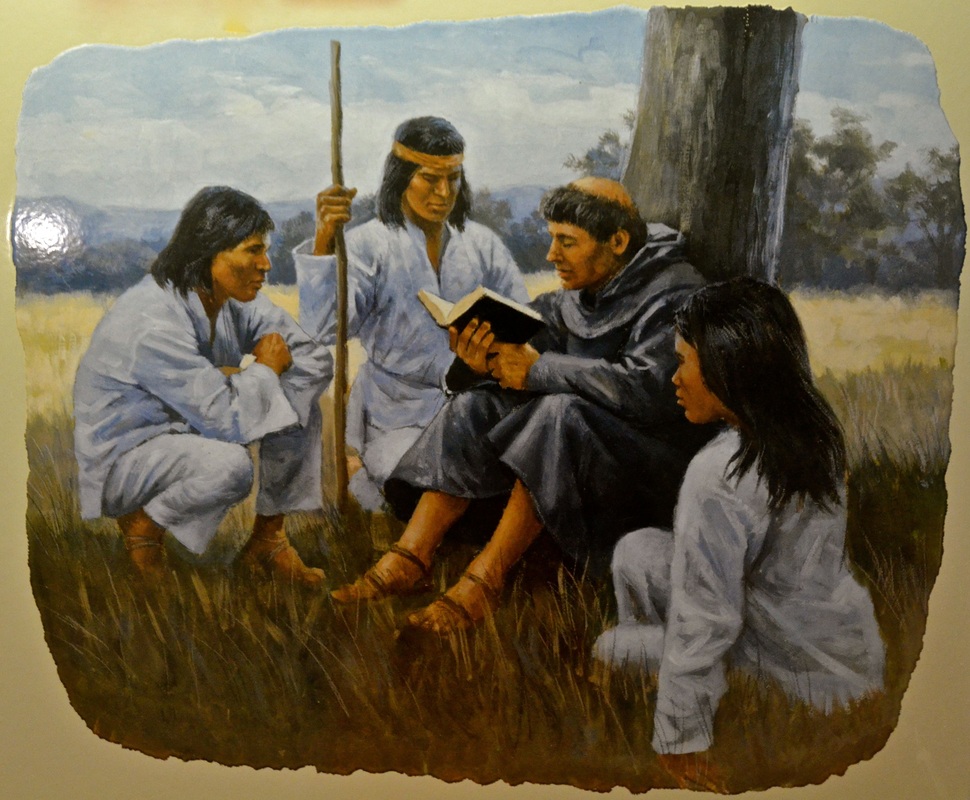

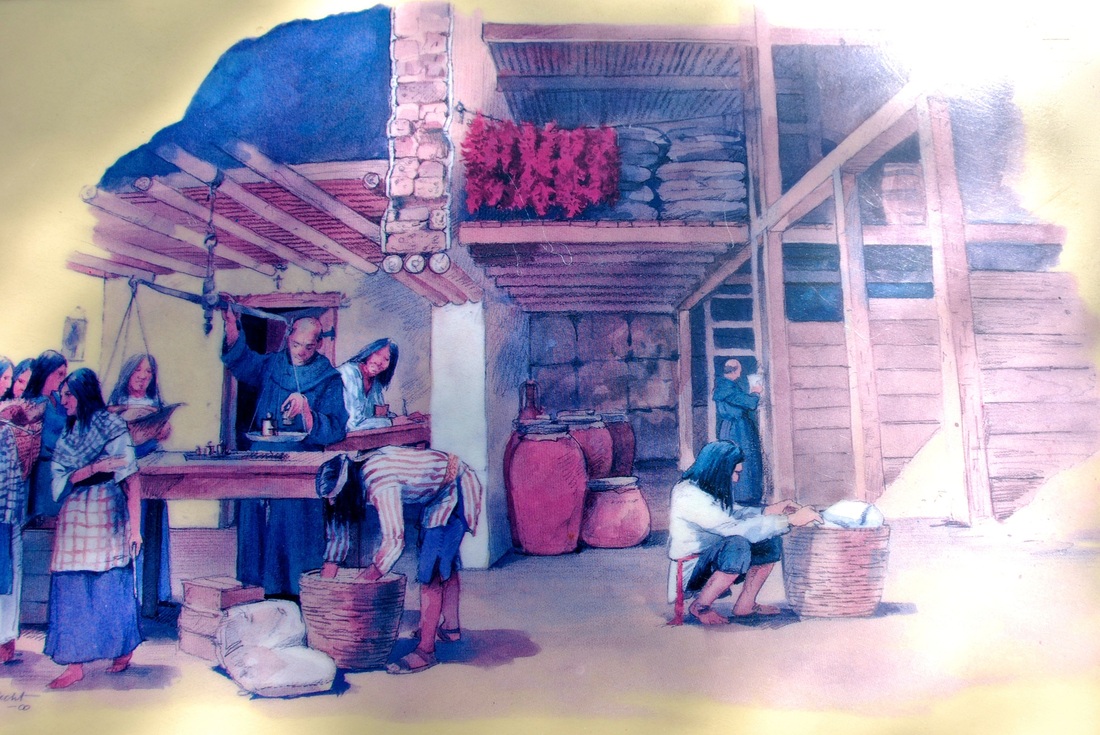

August 26, 2014 - When we think of the Spanish conquistadors, most of us see images of the ruthless explorers who committed genocide while seeking gold in Latin America. Those images often are grossly distorted by the anti-Spanish propaganda known as the Black Legend, but they are even more distorted when they are applied to the Spanish missionaries who came to North America. Nowhere is this more evident than on the San Antonio Mission Trail, where you can see marvelous things the Spanish did to improve the lives of Native Americans. You see housing quarters, schools, water wells, irrigation systems, flour mills, granaries, blacksmith workshops and beautiful churches. You see fortified communities that were built by natives under Spanish supervision almost three centuries ago and subsequently rebuilt and preserved as historic monuments. You see how Native Americans learned not only the Spanish language and traditions but also the skills needed to defend themselves; raise cattle, sheep, goats and pigs; grow crops; work with iron; produce textiles; make bricks; and build with masonry. Unless you live in Florida, the Southwest or California and you are used to seeing it with your own eyes, you might fail to recognize that the Spanish came here to teach new ways, build communities and preach Christianity. When my Great Hispanic American History Tour recently followed the San Antonio Mission Trail, I took a journey back in time to communities that were established between 1718 and 1731. And my Hispanic batteries were recharged! "The missions of San Antonio were far more than just churches, they were communities. Each was a fortified village, with its own church, farm, and ranch," according to the sign that greets you at the missions. "Here, Franciscan friars gathered native peoples, converted them to Catholicism, taught them to live as Spaniards, and helped maintain Spanish control over the Texas frontier." As you walk around these missions and see how they sustained thriving communities of Spaniards and Native Americans back in the 1700s, you also see how deeply Hispanic roots are planted in this area. "The Franciscans established six missions along the San Antonio River in the early 1700s," the mission signs say. "Five of them flourished and, with the Villa de San Fernando, became the foundation of the city of San Antonio." Of the five missions that survived, one of them — San Antonio de Valero — became known as the Alamo and now serves as the shrine for those who died there while fighting for Texas' independence from Mexico in 1836. But the other four, rebuilt from ruins and pristinely maintained as park grounds and museums by National Park Services, are also gems to behold — a photographer's paradise. And their four churches, administered by the Archdiocese of San Antonio, still are active and serving some of the descendants of Native Americans converted to Catholicism almost three centuries ago. San Antonio de Valero, established in 1718 and moved to its present location in 1722, was followed by San Jose y San Miguel de Aguayo, established in 1720. Two others, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purisima Concepcion de Acuña and Mission San Juan Capistrano were established in 1731. But Mission San Francisco de la Espada came before them all, in 1690. Each of them has an open courtyard, once bustling hubs of Native American commerce. All of them housed Native American families in the rooms along the interior of the compound walls. Although they were connected by the Mission Trail, each mission was a self-sustained community housing several hundred natives during their thriving decades. Those who follow the trail nowadays, on the same routes established by Spanish explorers in the 18th century, soon come to realize that, as the signs tell you, "today the missions are elegant reminders of the contributions of Indian and Hispanic peoples to the history of the United States." They are also elegant reminders of the many ways in which the Spanish taught the natives how to live much better lives and of how the natives joined the missions willingly. "Within the (mission) walls Indians lived, worshipped, and attended classes. They learned to blacksmith, to weave on European looms, to cut stone, and to make shoes and cotton clothes," according to the exhibit at the Mission San Jose museum. "Outside the walls, the mission Indians tended fields, orchards, and livestock." Not quite the image painted by the Black Legend, right? In fact, the goal of the missionaries was to teach the natives to live and worship as Spaniards and, ultimately, to exist independently. "Franciscan friars served the Church as ministers, teachers, and protectors of the Indians," one of the mission exhibits explains. "They served the king as explorers, diplomats, cartographers, builders and scribes. As frontier missionaries they spread the word of God and the language and culture of Spain." Even when the missions were closed — because Spain could no longer maintain them and the territory became part of independent Mexico in 1821 — "the priests distributed the mission's farmlands, animals and community tools among the natives that still remained." But when the missions were active — some for up to a century — natives flocked to take refuge in them, often fleeing from more violent natives. "In this part of Texas, the mission Indians were hunter-gatherers, and they were nomads," explained Bonnie Simons a terrific volunteer tour guide at Mission San Jose. "They spoke the Coahuiltecan language. But they were peaceful Indians, and the Apaches and the Comanches that were also in this area were fierce warriors and quite intimidating." She said the Coahuiltecan nomads' "lives were either feast or famine. One day might be an abundant day, and the next day might be a day of starvation. Yet within this (mission) system, they would never starve, and within this system, they were so much safer from the Apaches and Comanches. And that's why our missions here in San Antonio are built like fortresses." In fact, the Comanches and Apaches rejected acculturation and lived nomadic lives until well into the late 1800s, but the Coahuiltecans became Spanish citizens in the 1700s and changed from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers and skilled workers. Simons said many natives also went to the missions believing that they would be better protected from the European diseases that were affecting them. "You have to ask yourself, 'Why would hunter-gatherer nomads want to enter a mission frontier system?'" Simons said. "It certainly wasn't that they were all dying to become Christians or that they particularly wanted to learn a vocation. And they were not handcuffed and tied down and roped to come in; they came in voluntarily. They came because it was a better way of life for them." "So not all the Spanish were bad?" I asked. "Because I'm sure you know there is this thing called the Black Legend, which portrays the Spanish very negatively." But she interrupted before I could explain further. "Well, they did not do here what they did in South America. They did not," she added adamantly. "They did not do that here." More Americans should take her tour and listen to her carefully. American history often fails to recognize it, but by the 1700s, Spain had established missions, forts and settlements from Florida to California and as far north as St. Louis. Nevertheless, we are still on the Great Hispanic American History Tour, and there is much road ahead and historical ground to cover. Before we leave San Antonio, however, next week the tour must stop again at some of the city's most treasured historic sites to recognize the woman who saved them from destruction, even barricading herself in the Alamo. Did you know she was a Latina? COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM |

En español

|

Mission San Juan:

(San Juan Capistrano)

(San Juan Capistrano)

Mission Espada:

(San Francisco de la Espada)

(San Francisco de la Espada)

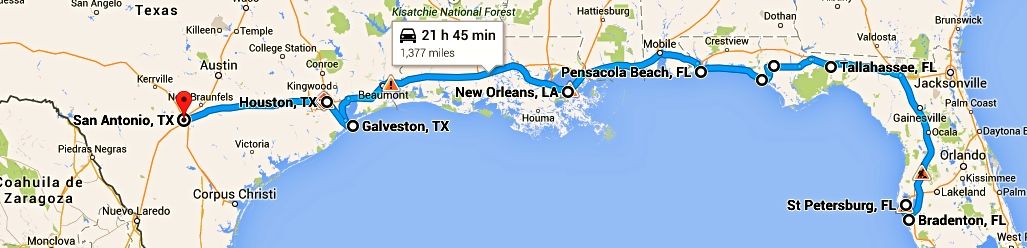

The Great Hispanic American History Tour is on the road again. Check out: California Road Trip

Please share this article with your friends on social media: