18. José Martí: His Legacy Lives Here

|

By Miguel Pérez

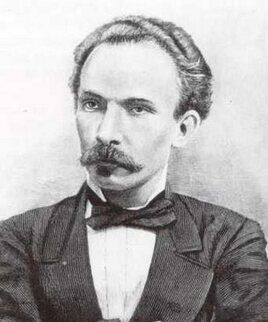

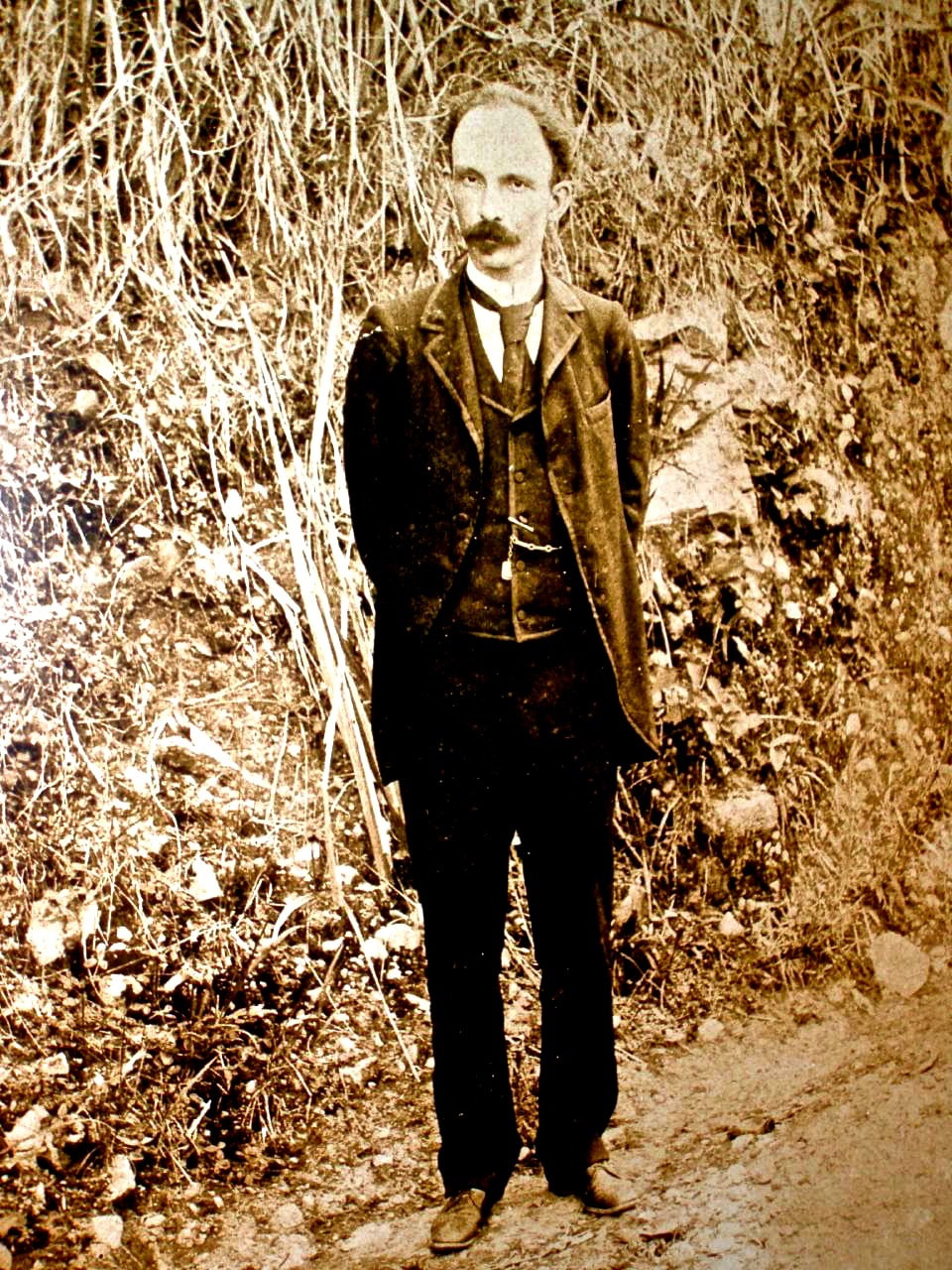

January 28, 2024 - You may have listened to his verses in the old Cuban song "Guantanamera." You may have seen his impressive statue in New York's Central Park. You may have heard him mentioned when Cuban-Americans and Washington politicians discuss the U.S. government radio and TV stations that bear his name, or when people cite streets, parks, schools or theaters that were named after him — in Cuba, the United States and throughout the Americas. His name was José Martí. You may know him as the still-revered poet, journalist and revolutionary leader of the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain in the late 19th century or as the remarkable writer and stirring speaker who fostered the ideals of freedom and democracy in Spanish America. This week, you could even be attending a civic or cultural event to commemorate the anniversary of his birth, which was in Havana on Jan. 28, 1853. All over this country and this hemisphere, there will be a multitude of banquets, lectures, recitals, writings and exhibits devoted to promoting Martí's teachings. And yet you may not realize that Martí's most important work — his legacy — was made while he lived in New York City and frequently commuted to Tampa, Florida during the last 15 years of his life. Latin American history books are filled with patriots whose most valuable contributions were made while they lived in exile in the United States. And perhaps Martí is the best example. It was here that Martí developed his concepts of liberation and emancipation. It was here that he represented the aspirations of all oppressed people struggling to be free. |

En español: Su Legado Vive Aqui |

|

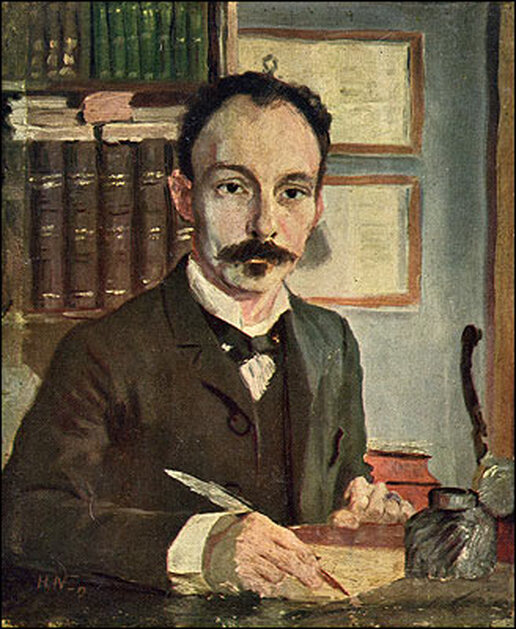

Between 1880 and 1895, from his Greenwich Village apartment, Martí emerged and flourished as a brilliant defender of liberty. Covering huge range of genres, he wrote an amazing volume of poems, essays, plays, letters and newspaper articles that inspired many generations of Hispanics to stand up and fight for freedom and democracy. In 1889, he even published Edad de Oro (Golden Age), a children's magazine. He was a correspondent for various Latin American publications and a writer for the old New York Sun and The Hour, becoming this country's first Hispanic columnist in English-language newspapers. His complete works occupy more than 50 volumes, and his most productive time was the 15 years he lived in New York.

|

|

He was also a diplomat who represented three South American countries (Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay). Aside from Spanish, he spoke English, Italian, Latin, French and Classical Greek fluently. He is still considered one of the greatest Latin American intellectuals and literary figures. Writers and patriots have emulated him for generations.

But perhaps his greatest accomplishment was the way he managed to unite Cuban freedom fighters, in exile and on the island. It was his leadership, charisma and reputable integrity that enabled the formation of the Cuban Revolutionary Party in 1892 and led to the eventual defeat of Spanish forces on the island in 1898. The party's mission was to create a free and independent Cuba for all Cubans, regardless of race or social status. Some background: Although Martí was born in Cuba of Spanish parents, his family returned to Valencia, Spain when he was four years old, and then back to Cuba two years later. But during his adolescence in Cuba, he began to express support for the cause of Cuban independence from the Spanish Empire. Since 1868, Cubans had already fought and failed to win independence from Spain in “the Ten Years’ War,” but young Martí felt Cubans needed to keep fighting. At an early age, he began writing political essays critical of Spanish colonial rule. In 1869, at the age of 16, Martí was arrested and charged with treason for co-writing a “reproving” letter to a friend who had joined the Spanish army. Although he was sentenced to six years in prison, after two years, in 1871, Spanish authorities forced him into exile in Spain, where he was able to make a living as a translator and continue his studies in law and philosophy while still speaking out and writing articles condemning Spanish rule of Cuba. |

MARTÍ MONUMENTS IN CUBA:

|

|

Because he was prevented to return to Cuba, after obtaining a law degree in 1874, Martí moved to Mexico City, where he freelanced for newspapers, continued advocating for Cuban independence. In 1876, he moved Guatemala City, where he was a writing professor. But he went back to Mexico in 1877 to marry Carmen Zayas Bazán, a young Cuban woman he met in Mexico City a couple of years earlier.

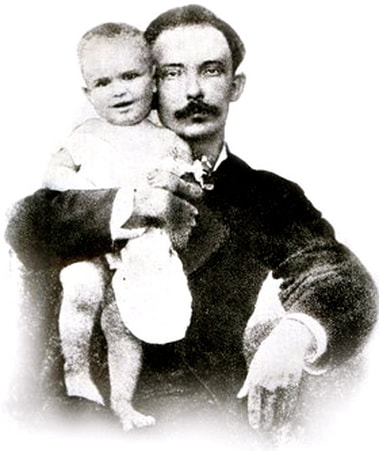

Together, they moved back to Guatemala, but only until Martí was allowed to return to Cuba at the end of the Ten Years War in 1878. Once back in Havana, they had a son, José Francisco, also known as "Pepito." But Martí returned to Cuba as a strong opponent of the Pact of Zanjón, which ended that war, because he thought it had little effect on Cuba’s status as a colony. And when his application to practice law in Cuba was denied, in a clear retaliation for his activism, Martí became even more involved with revolutionaries on the island. After he was deported back to Spain for a second time in 1879, Marti finally immigrated in 1880 to New York City, where he felt free to express his controversial opinions. |

MARTÍ'S TIMELINE IN PHOTOS:

|

|

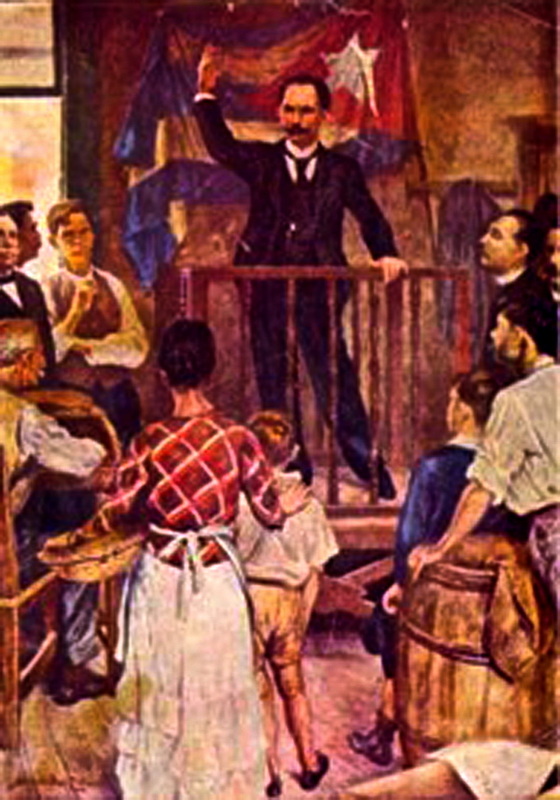

In a speech to Cuban immigrants in New York’s old Steck Hall, Martí charged that Spain had not honored the terms of the peace treaty and had continued excessive taxation, falsified elections and failed to abolish slavery, which was still practiced in Cuba and he adamantly opposed. He said Cuba was not free and another war needed to be fought. He said the Cuban suffering and heroism during the Ten Years War had already earned them the right to be an independent nation.

In 1881, Martí spent a short time in Venezuela where he started a publication that angered dictator Antonio Guzmán Blanco and was forced to return to New York. |

|

|

While in New York, he made a living as a freelance writer and book translator for the publishing house D. Appleton. But as an activist, he also translated Cuba-related pamphlets from Spanish to English. As a correspondent from New York, he wrote in Spanish for La Nación of Buenos Aires, La Opinion Liberal of Mexico City, La Opinion Nacional of Venezuela, and several other Hispanic publications.

In June of 1891, his wife and son joined him New York, only to realize that they could not compete with Martí’s devotion to his work and obsession with his cause. They returned to Havana two months later. He never saw them again. It was a hard blow for Martí. Perhaps for solace, he then began a relationship with Carmen Miyares de Mantilla, a Venezuelan woman who ran a New York boarding house and have him a daughter, Maria Mantilla, a concert singer who then gave birth to a son who turned out to be a famous Hollywood actor: The late Cesar Romero, would proudly acknowledge that Martí was his grandfather. Needless to say, Martí left roots in the city, and in American culture. While Martí did much of his writing in New York City, he did most his political organizing in Ybor City, the section of Tampa that had become the mecca for Cuban immigrants — the original Little Havana — in the late 19th century and early 20th. They turned Ybor City into “The Cigar Capital of the World,” with some 300 cigar factories employing thousands of workers. |

|

It was there that Martí found moral and financial support. It was there that he convinced exiled workers, mostly cigar makers, to get involved in the Cuban independence movement, and to raise funds that would finance the fight for Cuba’s independence.

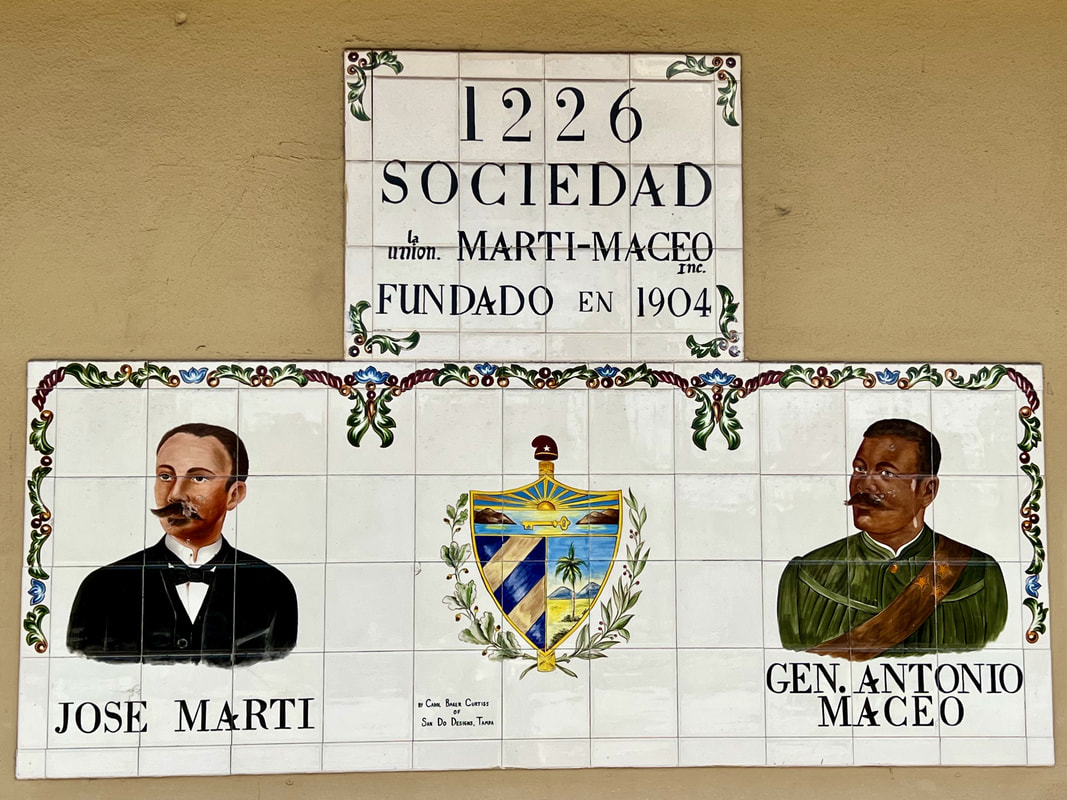

In Ybor City, which he visited numerous times starting in 1881, there were many Cuban and Spanish social clubs, each with their own clubhouse building, where Martí’s fiery speeches earned him the title of “Apóstol de la independencia cubana” (Apostle of Cuban Independence) and convinced political exiles to unite and to contribute a portion of their salaries to their common cause. Some of those clubhouses are still standing and are now considered National Historic Landmarks. |

|

The Liceo Cubano, a cigar factory that had been converted into a theater and social center in 1886, became Martí revolutionary headquarters. It was there that Martí delivered his two famous speeches, "Con Todos y Para Todos" and "Los Pinos Nuevos." And although El Liceo is no longer there, a historical marker shows the spot where it stood and calls it the “CRADLE OF CUBAN LIBERTY.” (See photo).

While New York recognizes him with a very impressive statue in Central Park, in Ybor City, Martí’s effigies are everywhere! There are statues and busts and even a park honoring his memory. At the Tampa Bay History Center, there is a huge photo of Martí and his followers in front of a cigar factory in in 1893. So, I couldn’t help myself; I took a selfie with them! LOL (See photo). "With Cigar City's largely Cuban workforce, the issues of Cuba were those of Tampa," a History Center exhibit explains. It notes that "During the 1890s, nearly every Cuban member of the Tampa workforce willingly pledged on day's salary per week toward Cuba's independence from Spain . . . From Tampa, Martí and other revolutionary leaders found a place to rally, recruit and train a growing force of insurrectos." |

|

At the end of 1891 and beginning of 1892, when news of Martí’s fiery speeches in New York and Tampa had reached the large Cuban community in Key West, leaders of that community invited Martí to speak at several events. Accompanied by delegations of Cuban exiles from New York and Tampa, on Christmas Day 1891 Martí travelled from Tampa to Key West aboard the steamship Olivetti.

They spent several days going to community meetings and cigar factories where Martí even took over the reader’s podium to explain that, if unity among Cuban exiles could be achieved, if Key West Cuban community leaders could drop their differences and coordinate their efforts with those in Tampa and New York, a successful war could be waged against Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. |

|

|

They went back to Tampa 12 days later, on January 5, 1892, feeling that they had realized the dream of uniting all Cuban exiles in the United States. It was perhaps Martí's greatest accompliment! If that sounds familiar, it's because it's the same dream that once again eludes Cuban exiles nowadays. Because need another Martí!

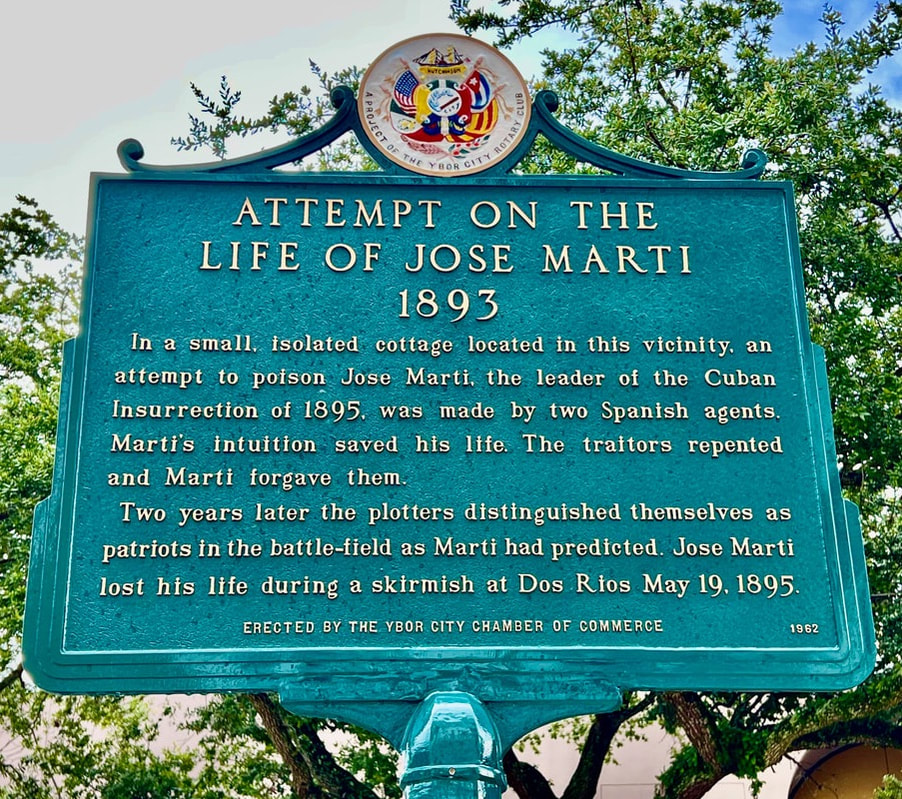

In March of 1892, Martí published his own newspaper, Patria, devoted to raising awareness of the need for Cuban freedom. In the summer of 1892 from his home in New York City, Marti traveled and delivered moving speeches in Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Florida, the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Jamaica in a campaign to raise support and funding for a revolution. In December of 1893, he survived a poisoning attempt in Tampa. Yet in 1894, Martí kept traveling, not only to promote his ideas, but to begin planning an uprising in Cuba with other exiled rebel leaders. In Montecristi, Dominican Republic, he met with Gen. Maximo Gomez, and in San Jose, Costa Rica, he met with Gen. Antonio Maceo Grajales. |

|

The apostle was back in New York shortly after his 42nd birthday in 1895 when he wrote and signed the order to begin the uprising against Spain in Cuba. It was passed through several revolutionary carriers assigned with smuggling the decree into the island. When it got to Florida, the document was rolled inside a Tampa cigar and carried to Havana from Key West by passenger on a steamer. After it was received by insurrectionists in Cuba, the War of Independence began on Feb. 24, 1895.

Martí then went to the Dominican Republic where he joined other revolutionaries before returning to Cuba to join the fight. His small expedition landed in Playitas, Cuba on April 11, 1895. But he never realized his dream of seeing a free Cuba! After joining Cuban rebels, he was killed by Spanish forces, at the age of 42, on May 19, 1895. His Central Park statue depicts the moment when he was fatally wounded as he rode a horse into battle at Dos Rios, at the confluence of the Contramaestre and Cauto rivers in Cuba's Oriente province. Those who fought for Cuba's freedom had lost their most prominent civilian leader, but Cuba and all the Spanish colonies had gained an eternal martyr. |

|

Martí had laid the foundation for Cuban independence from Spain, realized with the help of American troops in 1898, three years after his death. Yet Cuba did not become truly independent until the U.S. Army finally left in the island 1902. The Cuban War of Independence became known here as the Spanish-American War. Yet the History Center describes it more accurately: "The-Spanish-Cuban-American War." And Tampa had a huge role it all of it! Curiously, three years after Martí died in Cuba, Tampa also served as the official port of embarkation for American troops, led by Col. Teddy Roosevelt, on their way to Cuba in 1898.

In Ybor City, the land once occupied by the boarding house where Martí stayed is now the “Parque Amigos de José Martí.” And since the property was donated to the Cuban government, it is considered the only Cuban territory in the United States, other than the Cuban embassy in Washington, D.C. |

|

The park features a statue of Martí, a bust of Cuban independence General Antonio Maceo, a modest mural-map of Cuba, and the Cuban and American flags. It is covered with soil brought from each of the original six Cuban provinces! When you enter, you know you are stepping on Cuban soil. It's the only way to go to Cuba without a passport!

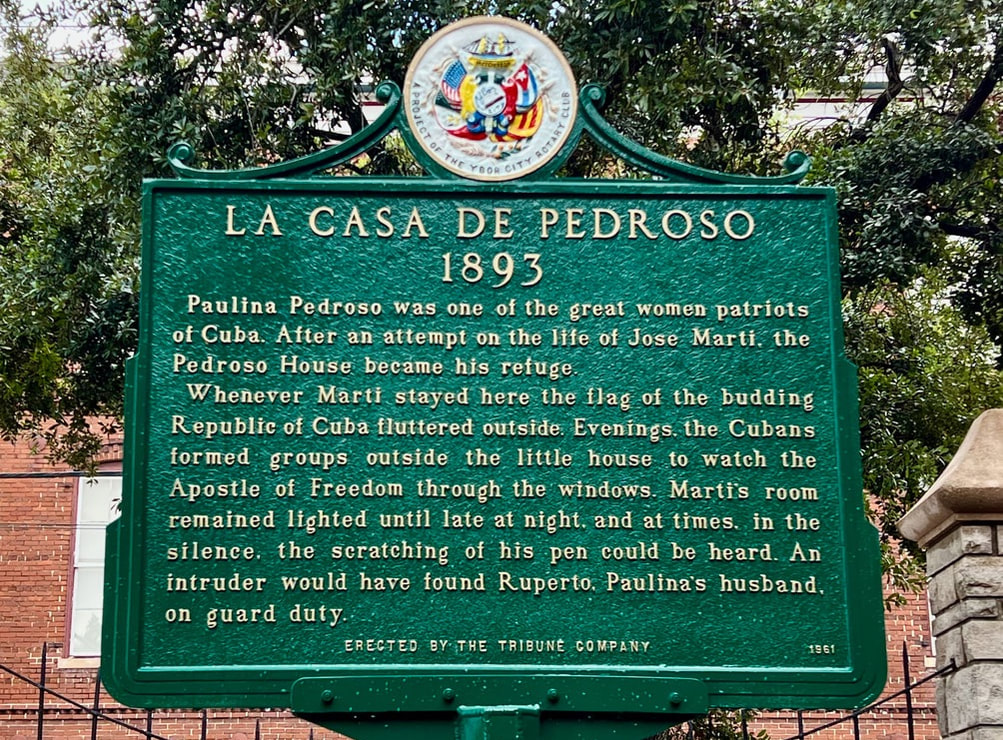

The boarding house that once stood there belonged to Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso, the Afro-Cuban couple who nursed Martí back to health after he has poisoned by two Spanish agents in 1893. Cuban folklore says that many years later, before she died back in Cuba, Paulina requested to be buried with a photo of Martí. On the back, it was dedicated by Martí "to Paulina, my black mother." |

|

The Pedroso house went through several transactions until it was purchased in the early 1950s by Cubans wishing to recognize its historic significance. When the property was donated “to the people of Cuba” and ownership was transferred to the Cuban government in 1956, at first there was talk of turning it into a museum. But when it was severely damaged by a fire, it was decided to turn it into a small park, which opened in 1960: "Parque Amigos de José Martí — dedicated to the memory of the patriot, poet, and journalist who led the island's revolution to win independence from Spain."

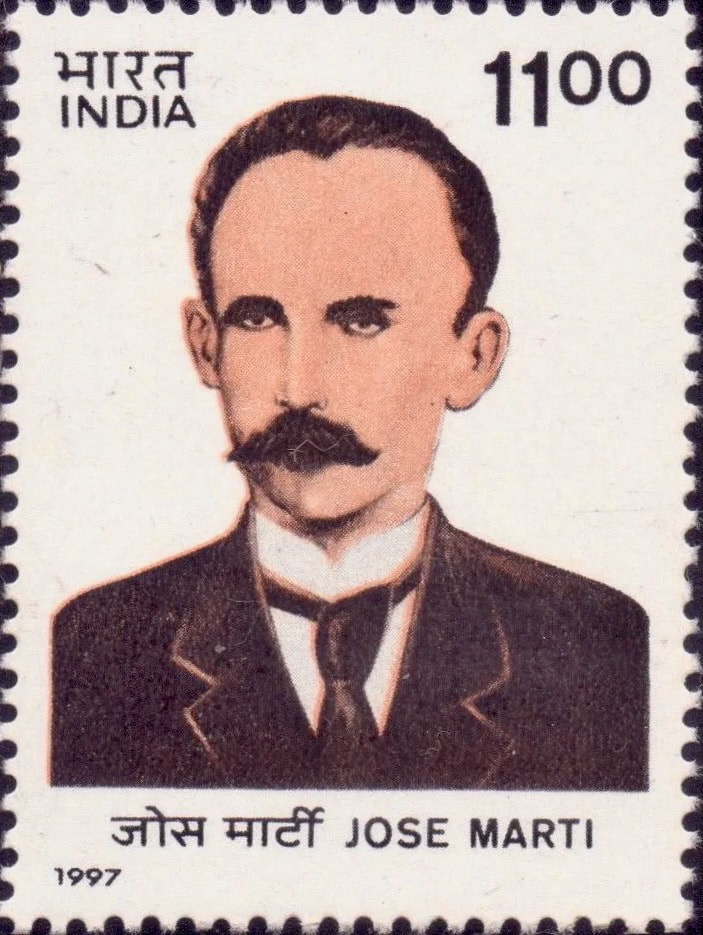

After his death, the teachings of the Apostle of Cuban Independence spread like wildfire throughout the Americas, where homes and public buildings were adorned with images of the man with the broad forehead, thick mustache and sincere smile. Latin American children were taught to emulate this ideal man, who was strong enough to be willing to die for his country yet sensitive enough to write beautiful love poems. |

|

After listening to the Cuban classic song "Guantanamera," some of my Hispanic history students assume that Martí was also a songwriter. Every semester, this gives me an opportunity to explain that only a few of Martí's "Versos Sencillos" (Simple Verses) were adapted into song lyrics long after he died, and that he wrote those moving, autobiographical verses while he recovered from an illness in Haines Falls, N.Y.

I also get to share some of my favorites, from when I recited them as a boy in Cuba. "Yo vengo de todas partes, y hacia todas partes voy: Arte soy entre las artes. En los montes, monte soy." (I come from everywhere and to everywhere I go. I am art among the arts. In the mountains, I am a mountain." |

|

As if history was repeating itself, in Little Havana's Cuban Memorial Plaza, a wall with map of Cuba features two Marti thoughts that perfectly illustrate the condition of Cubans who long to see their homeland free again:

• "La patria es agonía y deber". ("The homeland is agony and duty." • Yo quiero, cuando me muera sin patria, pero sin amo, tener en mi losa un ramo de flores, ´y una bandera! ("I want, when I die, without a country, but without a master, to have on a tomb a bouquet of flowers, and a flag)." |

|

However, Martí was such a prolific writer that his ideas have been extracted — and taken out of context — to defend almost any point of view, much in the same way that the Bible often is quoted to make opposing arguments.

Amazingly, at a time when Latin America is sharply divided between socialists and capitalists, both sides can claim Martí as one of their own. Depending on the perspective from which he is seen, Martí either was strongly anti-American or favored a Latin America in the image of the United States — either "the intellectual author" of today's Communist Cuba or a Cuban who would be exiled in New York again — if he were alive today — still struggling to free his homeland. In Cuba, the communists argue that Fidel and Raul Castro are completing Martí's revolution by defying the United States. But in this country, Cuban-Americans believe Martí could have been one of today's Cuban rafters, once again fleeing the island to be able to express himself freely, or perhaps one of Castro's political prisoners, serving time for writing articles that would be considered "counterrevolutionary" today. Indeed, some of Martí's writings, from more than a century ago, are censored in Communist Cuba, where the government is very selective about what the public is allowed to read. Cuban schools and books promote Martí's line about having lived in the "monster" that is the United States, but they censor his warning about the dangers of socialism and totalitarian leaders. "One revolution is still necessary,'' Martí wrote in his day, as could be written today, "the one that will not end with the rule of its leader.'' That's the side of Martí that Cubans on the island are not allowed to know. "A nation is not governed like a military camp," Martí wrote. |

|

|

Because they are told that the Castro dictatorship was Martí's idea, many young Cubans grow up hating a man they should admire. "If that was Martí's dream," a young Cuban once told me shortly after escaping from the island, "damned be the hour when he fell asleep."

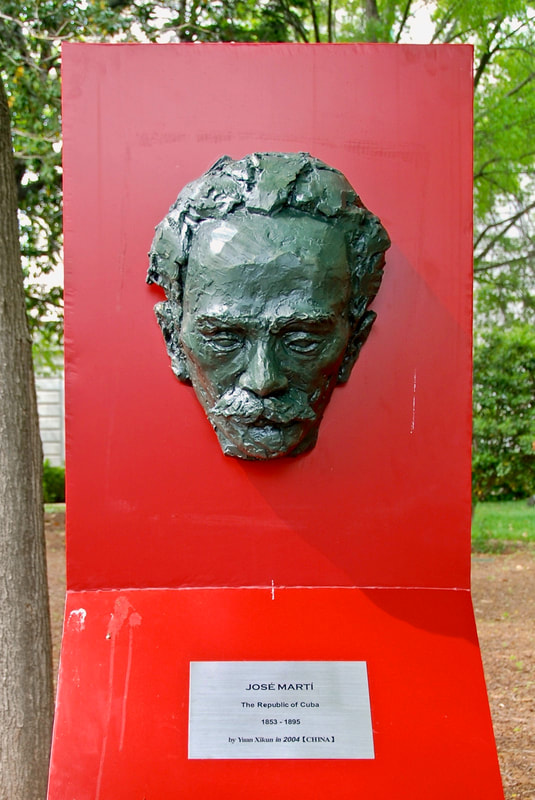

Carved on a plaque at José Martí Park in Union City, N.J., below a bust of Martí, the Cuban apostle's words describe the reason Cuban-Americans gather there instead of their homeland to play their beloved game of dominoes. "Man loves liberty, even if he does not know that he loves it," Martí wrote. "He is driven by it and flees from where it does not exist." Aside from the numerous Martí monuments in Cuba, his statues are all over Latin America. Aside from the numerous times his image has been honored in Cuban postage stamps, other countries have done the same. (See images). In Cuban communities in this country, there is always a bust of Martí to whom flowers are brought every January 28. |

|

With the passage of time, U.S. Hispanics could be expected to slowly forget their homeland heroes. But when those heroes also lived here, when they were also pioneers of the U.S. Hispanic community, we continue to identify with their struggle for freedom and social justice — especially when their fight does not appear to be over.

As this country's pioneer Hispanic columnist, Martí even outlined the mission for Hispanic journalists today and the path I have chosen to follow with my own column: "What I want is to demonstrate that we are good, industrious, and capable people," Martí wrote in a letter to a friend in Mexico. "For each offense, a response ... (made) more effective by its moderation. For every false assertion about our countries, an immediate correction. For each defect, apparently just, which is thrown in our faces, the historical explanation that will excuse it, and the proof of the capacity to remedy it. Without defending, I don't know how to live. It would seem to me that I were being derelict in my duty if I could not realize this thought." Part of this column was originally published by Creators.com as Cuba's José Martí: His Legacy Lives Here, on January 21, 2014. |

The lyrics of "Guantanamera" are based on Martí's poetry. Listen to The Sandpipers on YouTube: youtu.be/hFIATa8XIaQ

|