80. Smithsonian Omits Hispanics

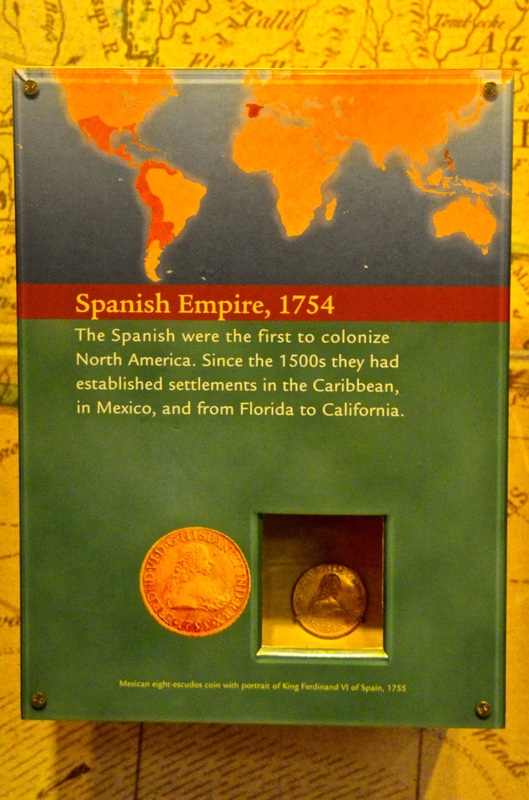

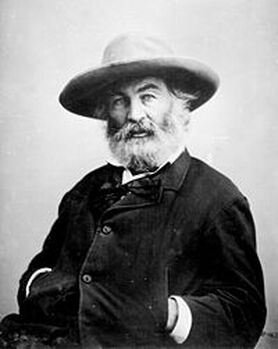

In U.S. History Exhibit

|

By Miguel Pérez

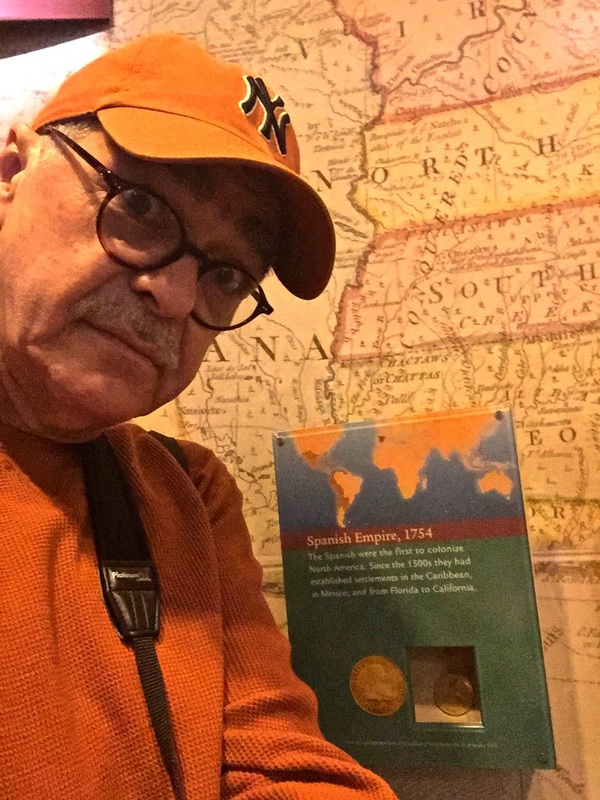

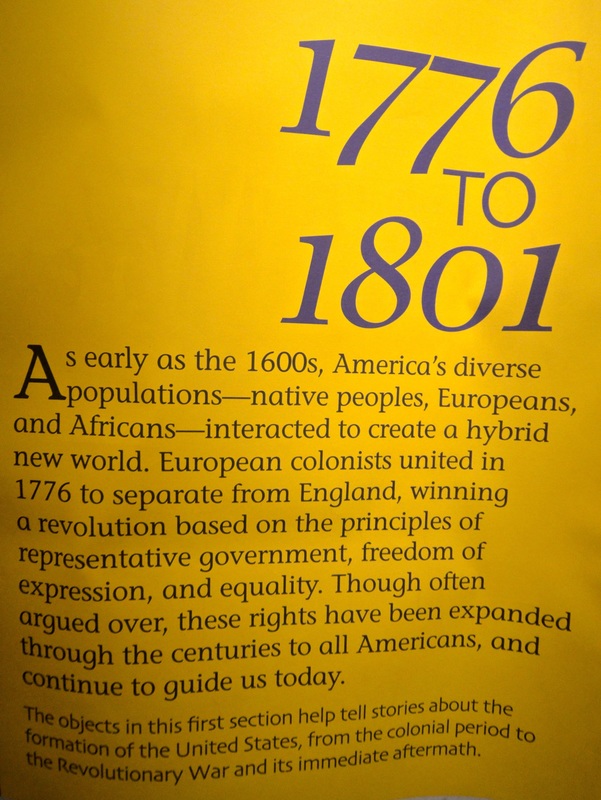

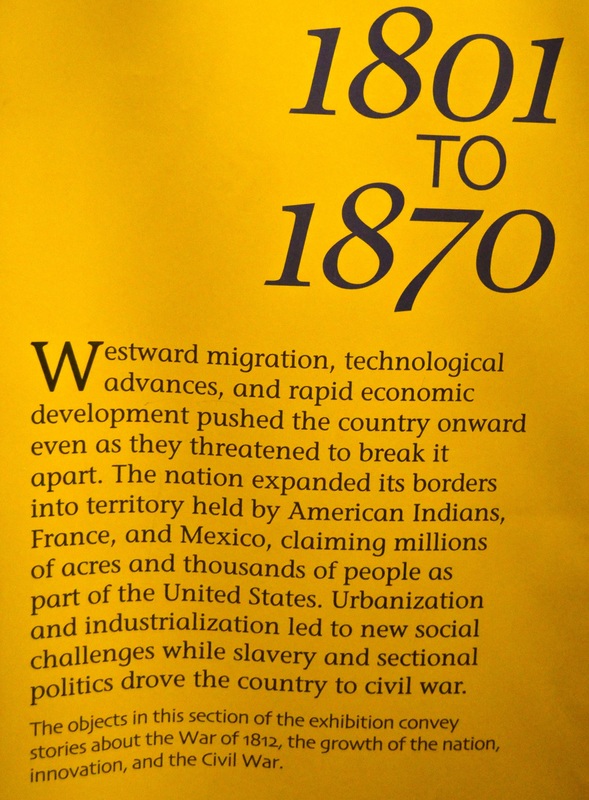

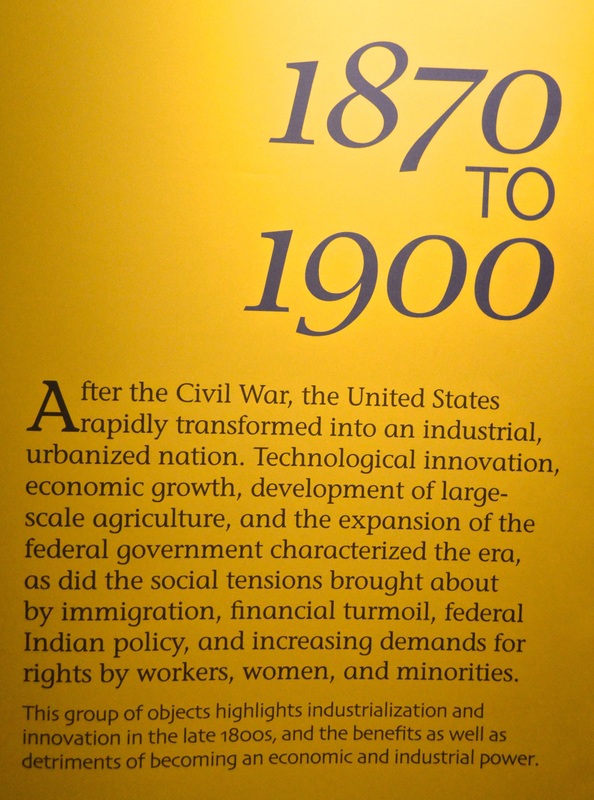

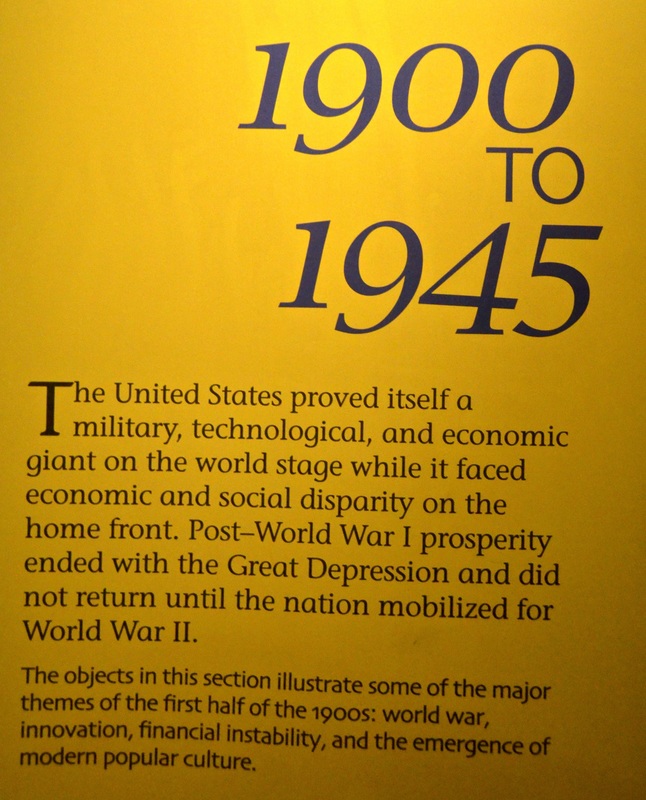

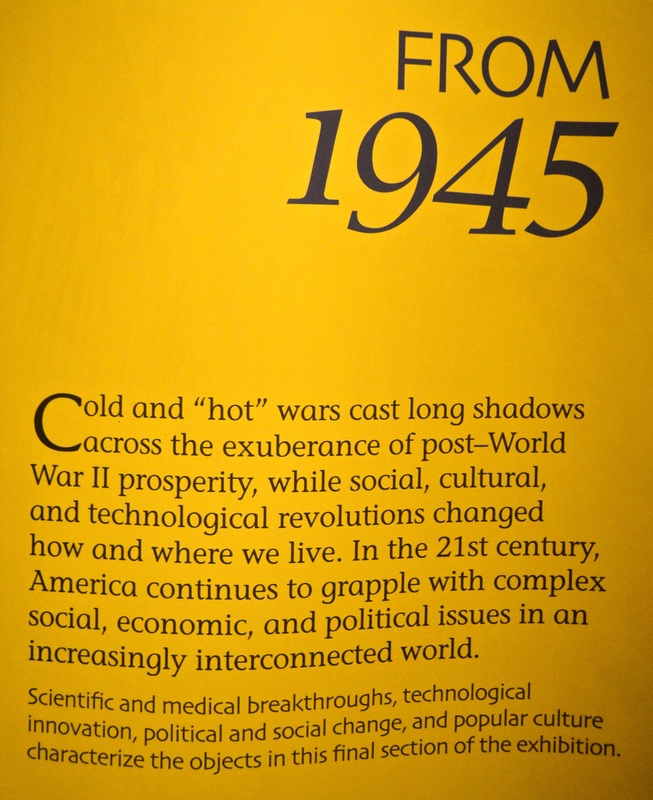

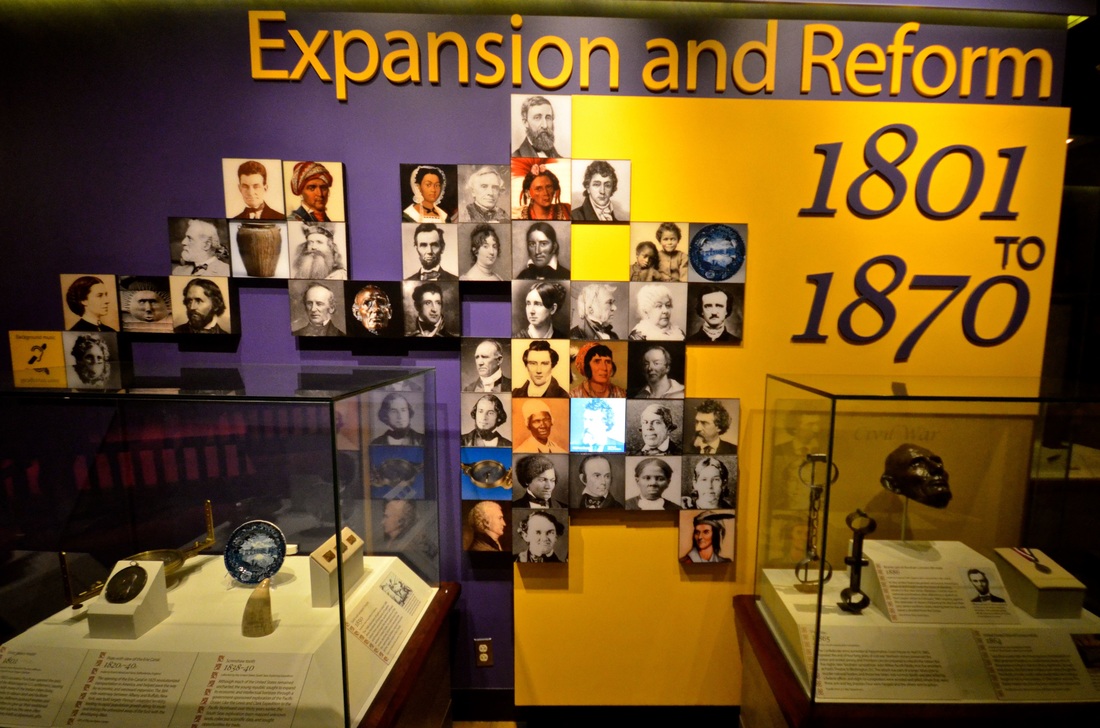

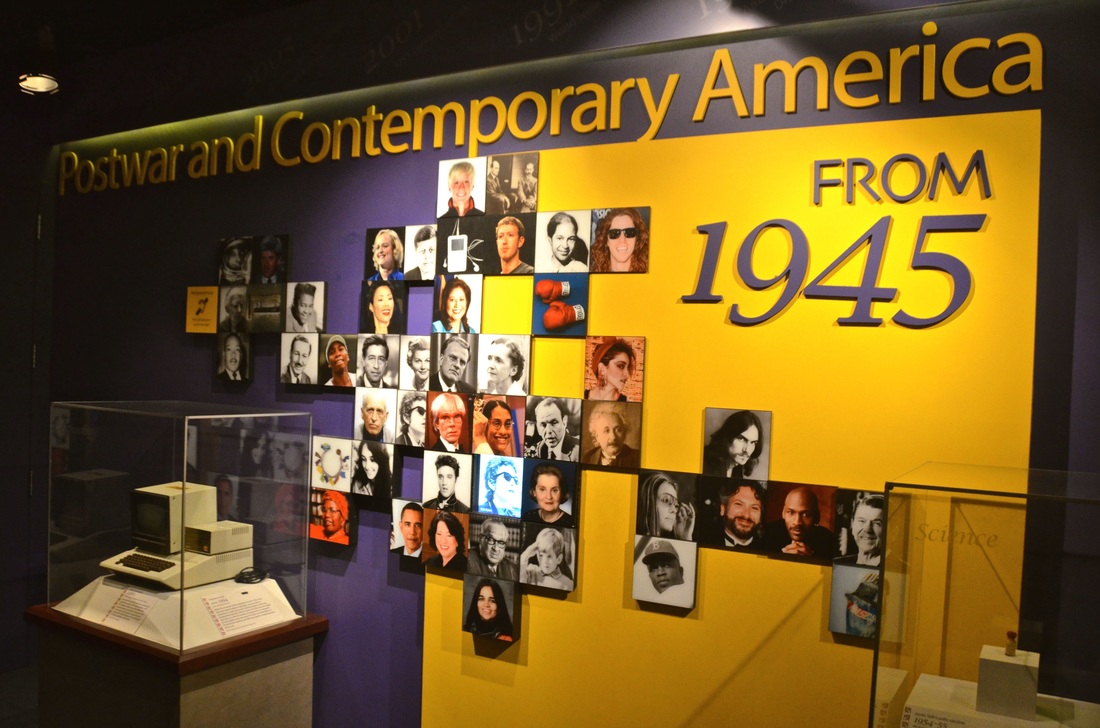

June 9, 2015 - On the broad streets of Washington, D.C., and within the majestic halls of the U.S. Capitol, our often-hidden Hispanic heritage had not been hard to find. My Great Hispanic American History Tour had discovered many remarkable monuments and works of art recognizing Hispanic patriots and heroes and their contributions to this great nation. I was truly impressed — until I got to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. Wow! After visiting so many Hispanic historical sites around the country, what a disappointment! It was as if I had walked into an average American history book, with all its typical blatant omissions of the contributions of Hispanic Americans. I was amazed to find that "American Stories," the museum's main exhibit outlining American history, rudely and disrespectfully begins in 1776 — and omits the 263 years when mostly Spanish settlers explored and built this nation, starting in 1513, when Juan Ponce de Leon discovered what is now the U.S. mainland. Among these "American Stories" — represented by photos of prominent Americans — you see many white, black and Native American faces. But I was dumbfounded by how few Hispanic faces are part of these montages. The exhibit is broken into several periods of American history, with large displays devoted to "1776-1801: Forming a New Nation, 1801-1870: Expansion and Reform, 1870-1900: Industrial Development, 1900-1945: Emergence of Modern America, 1945-Present: Postwar and Contemporary America." As if Hispanics were latecomers instead of pioneers to American history, I found only two Hispanic faces in "American Stories," and they were both on the 1945-present display — union leader Cesar Chavez and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. But I kept looking for a display that wasn't there. I kept searching for one that could have been called "1513-1776: The Mostly Spanish Exploration and Settlement of North America." Unfortunately, in this museum, that portion of American history has obviously succumbed to that centuries-old anti-Hispanic propaganda known as the Black Legend — which leads many historians to distort or omit Hispanic American history. All I found about those missing centuries was a tiny map of the Spanish empire in 1754, with a caption noting that "the Spanish were the first to colonize North America. Since the 1500s they had established settlements in the Caribbean, in Mexico and from Florida to California." And that was in another part of the museum! You really have to look all over this vast museum to find that short paragraph. Yet "American Stories," the big exhibit with huge displays, blatantly avoids giving credit to Spanish accomplishments. The museum's website notes, "'American Stories' highlights the ways in which objects and stories can reinforce and challenge our understanding of history and help define our personal and national identities." Really? Certainly not for Latinos! Although the exhibit begins in 1776, it does make an exception, rewinding back in time to feature a "Fragment of Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts said to be where the Pilgrims landed in 1620." The museum's website notes that the exhibit features more than 100 objects, through which "visitors can follow a chronology that spans the Pilgrims' 1620 arrival in Plymouth, Massachusetts, through the 2008 presidential election." If you follow this exhibit, you can easily be misled into believing that American history began only after the British arrived. The omissions are downright embarrassing and offensive. "The story of Plymouth Rock often obscures the history of earlier European and British settlements, such as Jamestown, Virginia as well as the arrival of enslaved Africans as early as 1619," the exhibit explains. That's true. But exhibits such as this one often obscure the history of earlier Spanish settlements, such as St. Augustine, Florida, as well as the arrival of conquistadors from the Caribbean and Mexico as early as 1513. This great irony kept reminding me of Walt Whitman's great quotation on this subject: "We Americans have yet to really learn our own antecedents," Whitman wrote in an 1883 letter celebrating our Hispanic heritage, as if he were referring to a 21st-century Smithsonian museum. "Thus far, impressed by New-England writers and schoolmasters, we tacitly abandon ourselves to the notion that our United States have been fashioned from the British Islands only, and essentially form a second England only — which is a very great mistake." Indeed, Mr. Whitman! Indeed! But how can these blatant omissions still be occurring in the 21st century? When I expressed my concerns to Melinda Machado, the museum's director of communications, she kept trying to switch the conversation to future exhibits in which the museum plans to be more inclusive of Latinos. She said the museum is about to launch a new exhibit called "American Enterprise," which will take a chronological look at the history of American business. "I think it's going to do a better job of telling — you know, unpacking — some of the Latino stories," she said. Machado explained that some of the stories in the "American Stories" exhibit have been rotating and that at some point, the exhibit included a display on the Hispanic quinceanera (15th birthday) tradition and a tribute to baseball superstar Roberto Clemente. Yet I've been there twice in the past two years, and both times I missed the quinceanera and Clemente rotations. I never saw them. To preserve exhibit items properly, Machado said many fragile materials couldn't be kept on display indefinitely, and that's understandable. But it left me wondering why even the photographs of the quinceanera dress and Clemente's batting helmet were removed from the online version of the exhibit. Machado said that she has heard concerns before when the museum has had "special and changing exhibits where topics are covered but then they go away" and that she would pass my "frustration" along to the museum's curatorial team. "It's unfortunate, but it doesn't surprise me," said Cid Wilson, a member of a Congress-appointed commission that in 2011 proposed the creation of a Smithsonian National Museum of the American Latino. "That just reiterates the argument that we are making that we need our own permanent museum," he added, "so that there is always a Latino story on display, 365 days of the year." While legislation that would jump-start the fundraising, designing and building of that museum is stagnating in Congress, Wilson said the idea of creating at least a permanent Hispanic gallery somewhere within the existing Smithsonian museums is long overdue. Latinos have a long history of heroism and sacrifice fighting to defend the United States, yet in the National Museum of American History's "The Price of Freedom — Americans at War" exhibit, except for a reference to Union Navy Adm. David Farragut, the only times I saw Latinos were when they were fighting against the U.S. in the Mexican-American and Spanish-American wars. There are two small Latino-themed exhibits — one devoted to Cuban superstar salsa singer Celia Cruz and the other to the Mexican Day of the Dead tradition — but they come across as very small efforts to make up for the whitewashing of Hispanic American history. Throughout the museum, you are given the impression that North America was explored and settled from east to west by people who spoke English instead of from south to north and more than a century earlier by people who spoke Spanish. Remarkably, in anticipation of a new African-American museum scheduled to open in 2016, the National Museum of American History has a "National Museum of African American History and Culture Gallery." But no such gallery has been created to anticipate the museum that will celebrate Hispanic history and culture. And the time has come to ask: Why not? "This is something we would like to see," Wilson said. "We are looking to establish at least a gallery until we get a museum." Machado said there have been discussions about hosting such a gallery at the history museum "when the African-American History and Culture (Gallery) departs." But she noted that although that space could conceivably become available in 2016, "it gets complicated." Wouldn't you know it? Just when Latinos are seeking their share of the American pie, that portion of the building is scheduled for reconstruction at that time. In a 1994 report titled "Willful Neglect," the Smithsonian recognized that U.S. Latinos were the only major contributors to American civilization not permanently recognized by that institution's many galleries. Yet more than 20 years later, there is still no room at the Smithsonian Inn for a permanent Hispanic gallery. I don't know whether the neglect is still "willful," but it certainly remains disgraceful. Mind you, the Smithsonian has its own "Latino Center," created in 1997 to deal with the "willful neglect" exposed in 1994, and it has done a good job promoting Hispanic exhibits all over the country. But it cannot possibly control the treatment of Latinos in all Smithsonian exhibits, and with the insensitivity displayed in some Smithsonian exhibits, it's obviously not enough. There is an underrepresentation of Latinos in American history in the Smithsonian museums, and it has to stop. Within the Smithsonian, there are Latino curators who say they have made great strides in adding Hispanic content to the institution's collection in recent years, but even they will tell you they know it's not enough. They tell you there is politics, bureaucracy and excuses preventing Latinos from getting their own museum in the near future and their own permanent gallery as early as mañana. IMPORTANT UPDATE: Although this column was written in 2015, I returned to the museum in 2018, and the "American Stories" exhibit was still there, exactly the same. The physical exhibit was finally dismantled in 2020! However, the online version of that exhibit (with all its omissions) remains on the museum's website. Check out: https://americanhistory.si.edu/american-stories SECOND IMPORTANT UPDATE: After resisting for many years, on December 21, 2020, Congress finally approved legislation to start the process of creating a national Latino museum. "We have overcome tremendous obstacles and unbelievable hurdles to get to this historic moment, but as I've said before, Latinos are used to overcoming obstacles," said Sen. Bob Menendez, D-N.J., who co-sponsored the bipartisan legislation to create the "National Museum of the American Latino." There were many articles about the struggle to reach this victory, and I've created a page with links to many of them. Check out: The Fight for a Latino Museum THIRD IMPORTANT UPDATE: UPDATE: I returned to Museum of American History in the summer of 2022, and found that things have changed considerably! Check out Stop 40 in On the Road Again. |

En español

|

Please share this article with your friends on social media: