On the Road Again

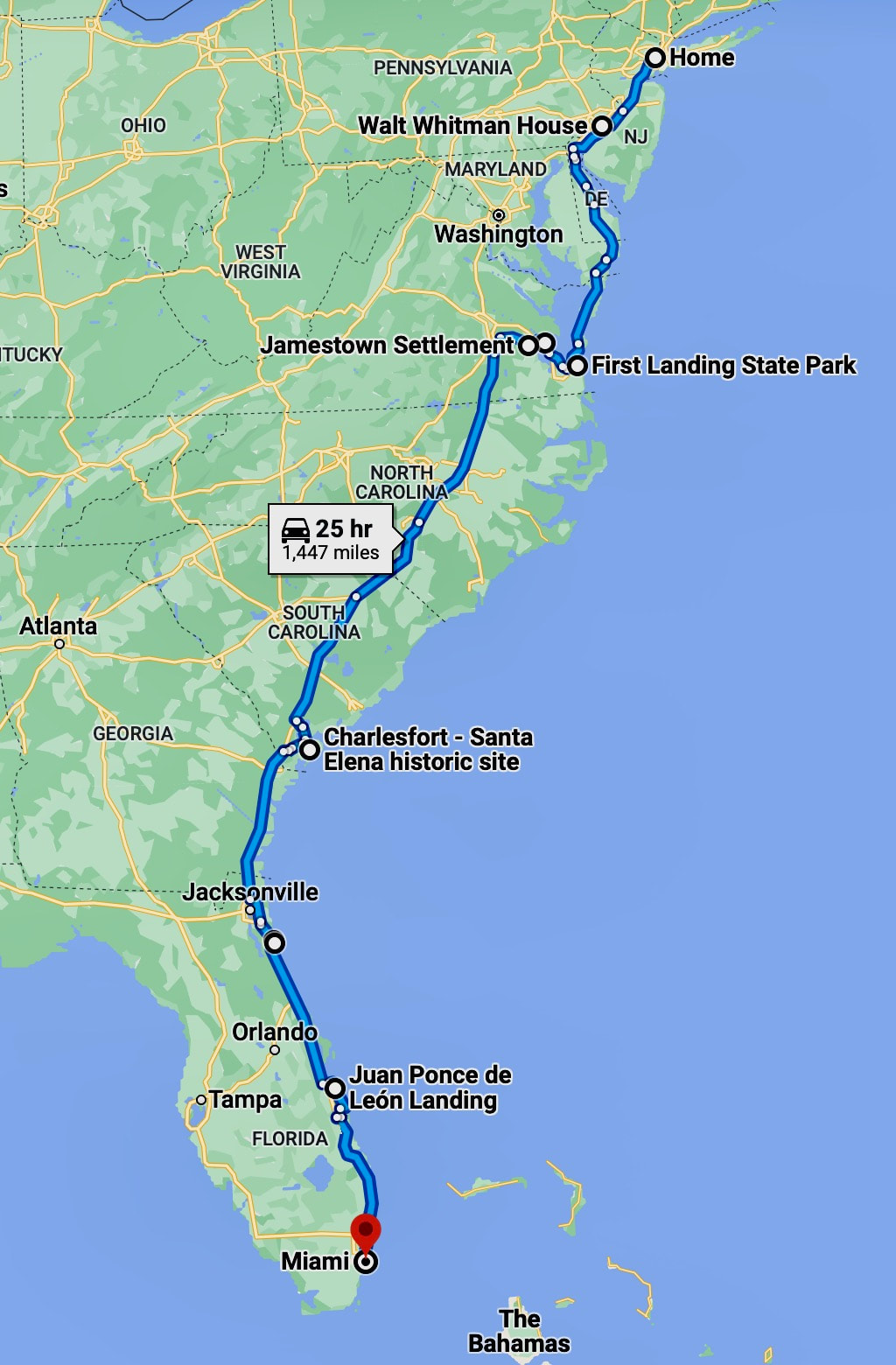

|

|

|

|

40th stop: Smithsonian Steps Up

|

|

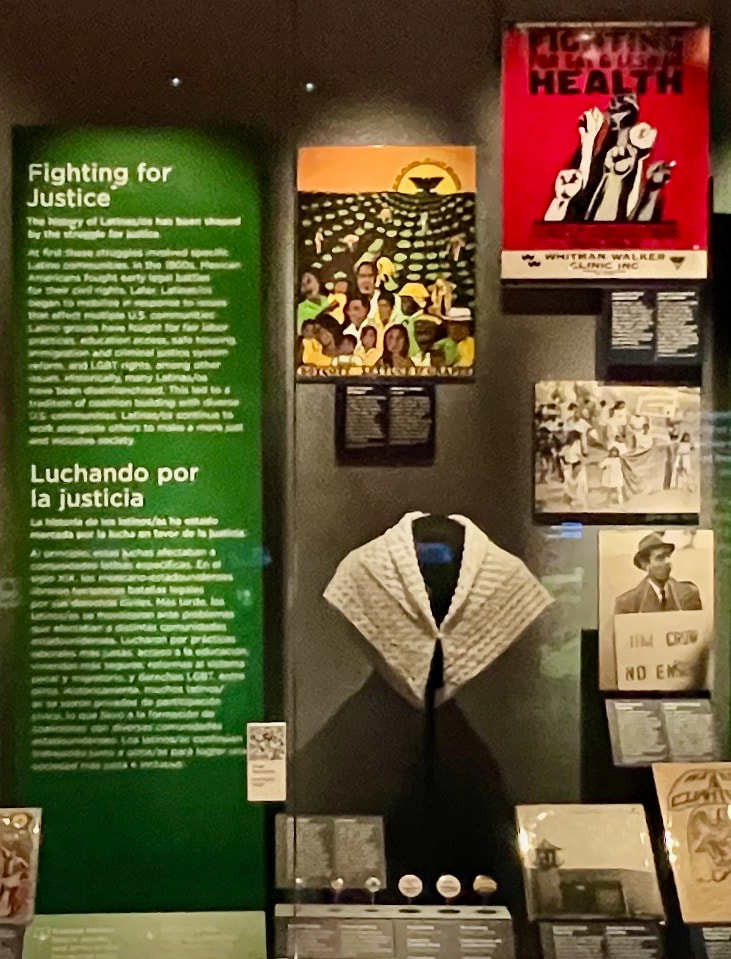

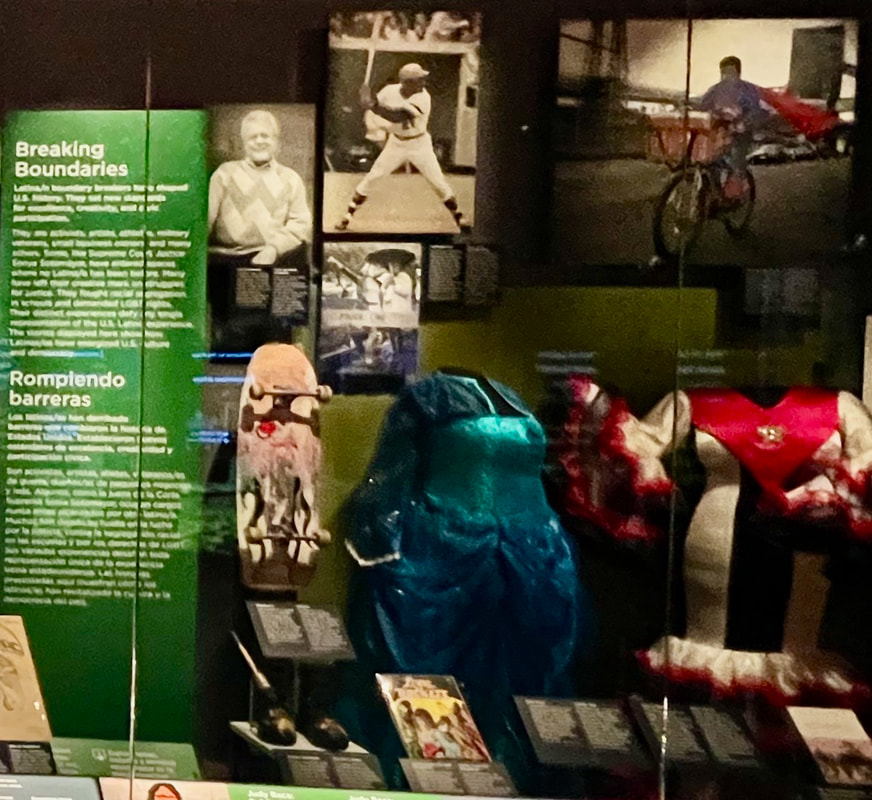

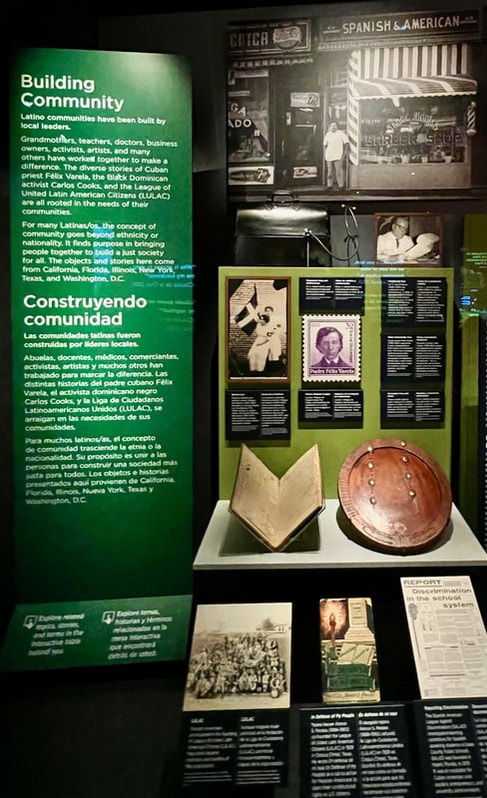

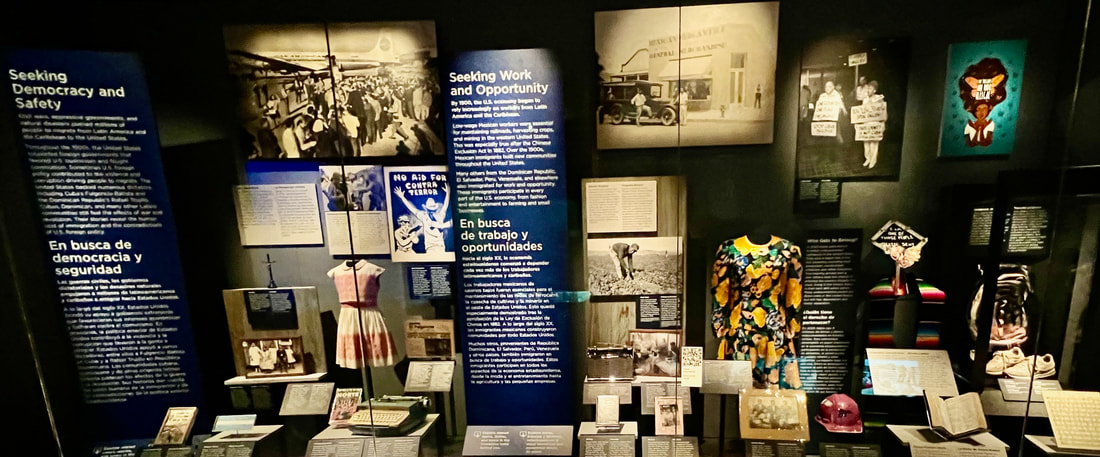

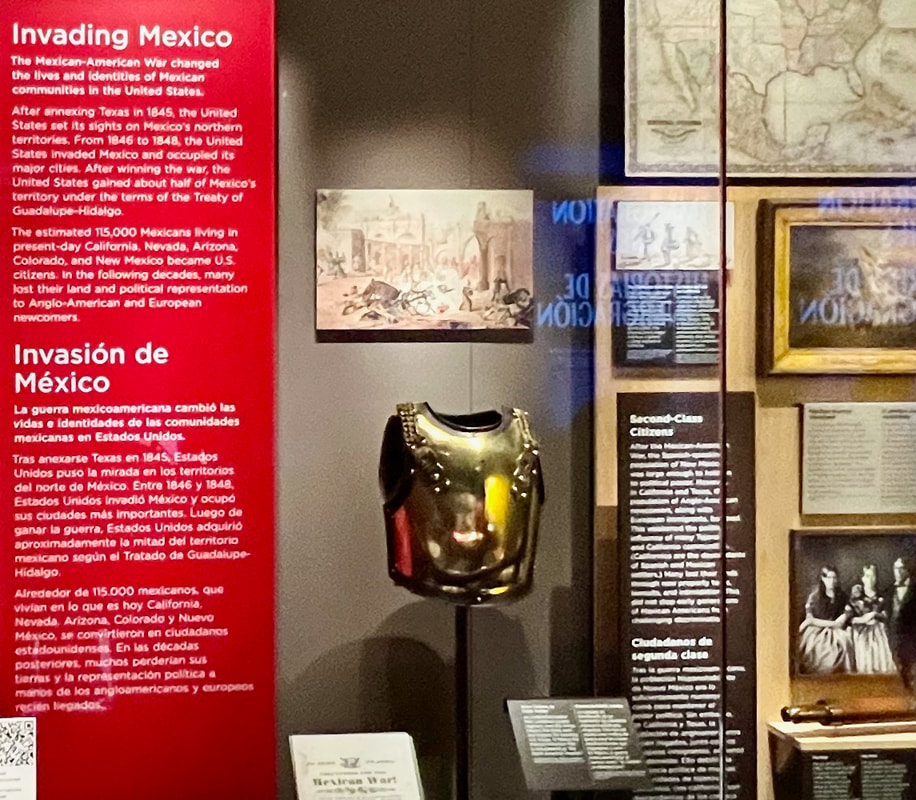

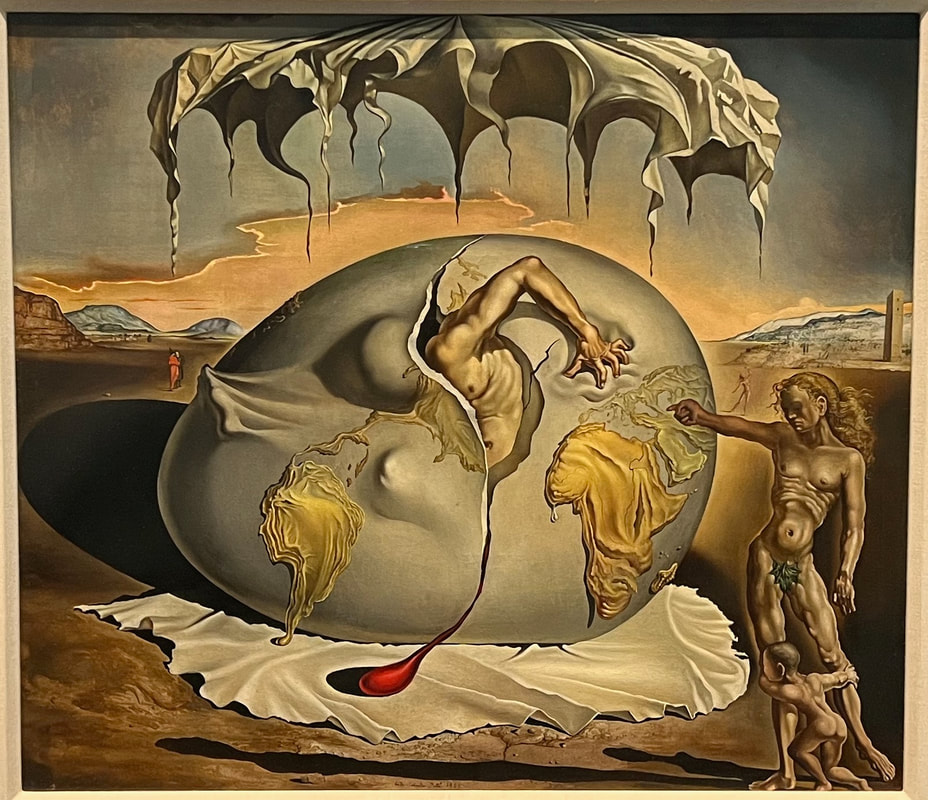

This exhibit is an anticipation of the "National Museum of the American Latino," which was finally approved by Congress in 2020 and is expected to be built on the Washington Mall in the next few years, although the location is still in question.

As readers of my columns know, I have been calling for the creation of this museum for many years, and it's great to see it being realized. (See links to my 2011 and 2015 columns below). This goes all the way back to 1994, when looking at itself in the mirror, the Smithsonian realized it wasn't painting an accurate image. That's when a Smithsonian task force issued a report, titled "Willful Neglect," which concluded that they had ignored the contributions of Hispanics/Latinos in their exhibitions — and that a new national museum was needed to fill the huge void they had left in their many museums. |

|

So, 30 years later, I expect to see this dream under construction by 2024, if we are lucky! ´Dios mio, dame paciencia!

But perhaps it could be a little sooner and at an appropriated site after President Joe Biden recently endorsed a push by the Congressional Hispanic Caucus to build this museum on the National Mall in Washington. Once they decide on a site, the dream will become reality much sooner. |

|

|

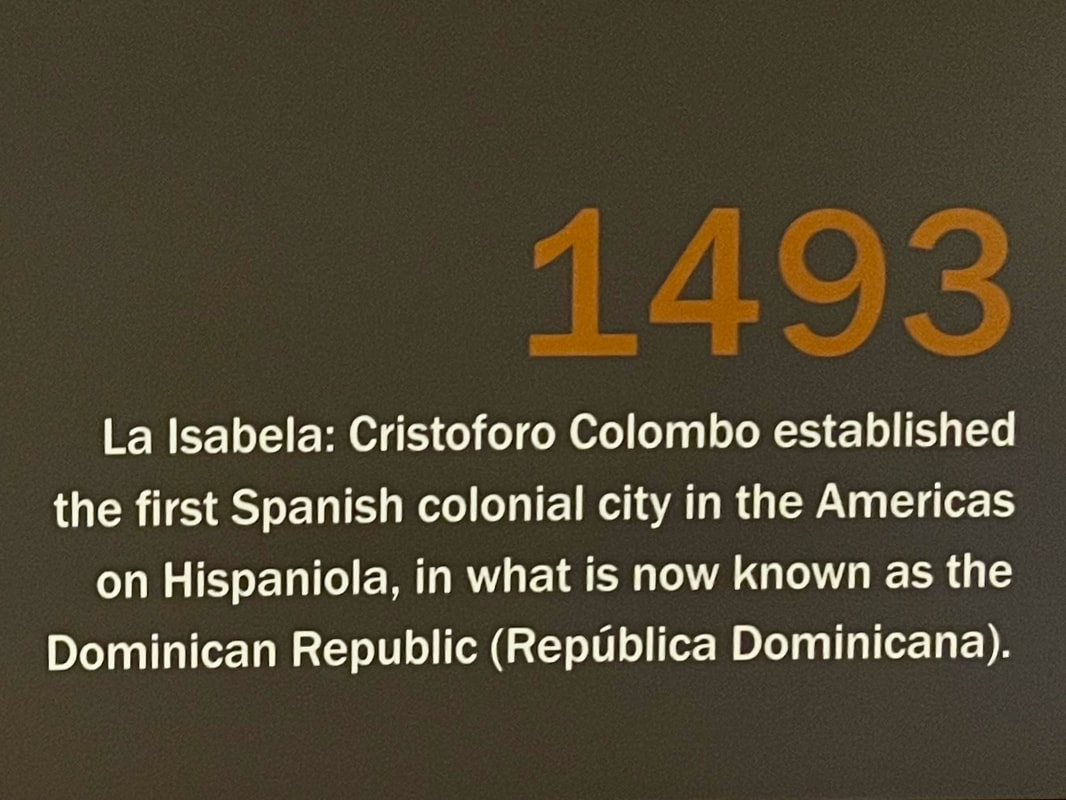

However, I would have called it the "National Museum of Hispanic American History." I fear that without "Hispanic" in the name, it would be hard for the museum to represent that period of history when we were not yet Latinos, especially our Spanish ancestors who came in that first century before the British arrived. And without "History" in the name, I fear that it could easily turn into a pop culture museum.

Already, the PRESENTE exhibit is mostly about U.S. Latinos in the 19th and 20th centuries. I saw very little about our ancestors from that first HISPANIC century They were hardly presente! |

|

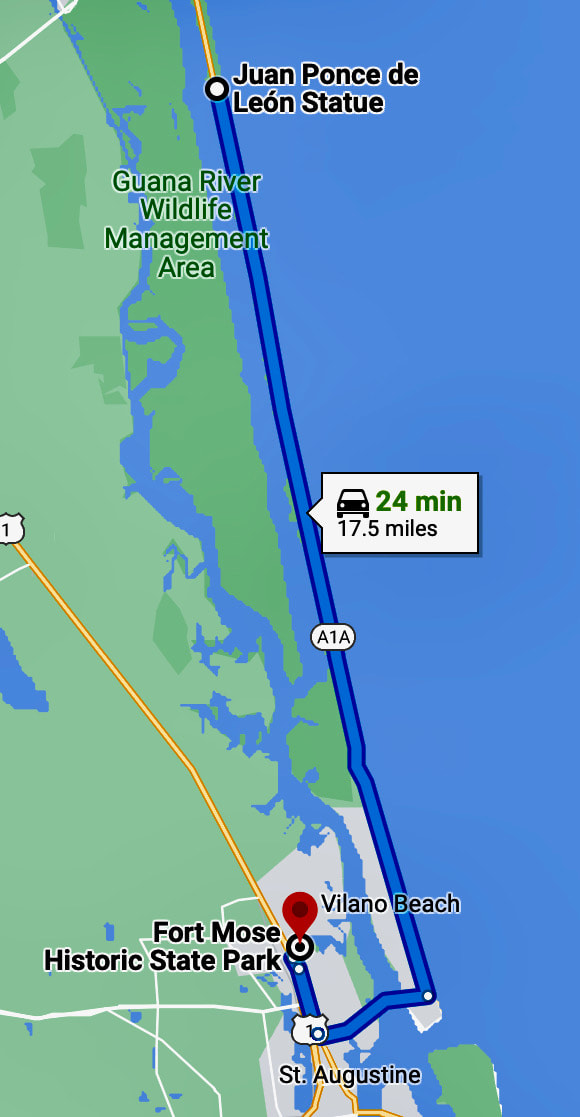

After visiting Fort Mose in Florida (our seventh stop) a few weeks ago, I was glad to see the exhibit recognizes Capt. Francisco Menéndez. But I could not find the huge historial figures we saw in Florida museums during this trip. Juan Ponce de Leon, Pánfilo de Narváez, Juan Ortiz, Estevanico, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Pedro Menéndez de Aviles, and Hernando De Soto were not presente! And neither were Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and many other explorers who came north from present-day Mexico during that first Hispanic American century.

Was that more "Willful Neglect?" I certainly saw that kind of intentional snub of U.S. Hispanic history as this very museum when I visited in 2015 and 2018, and the main American history exhibit began in 1776, conveniently omitting that first Hispanic American century. See my 2015 column, Smithsonian Omits Hispanics In U.S. History Exhibit. |

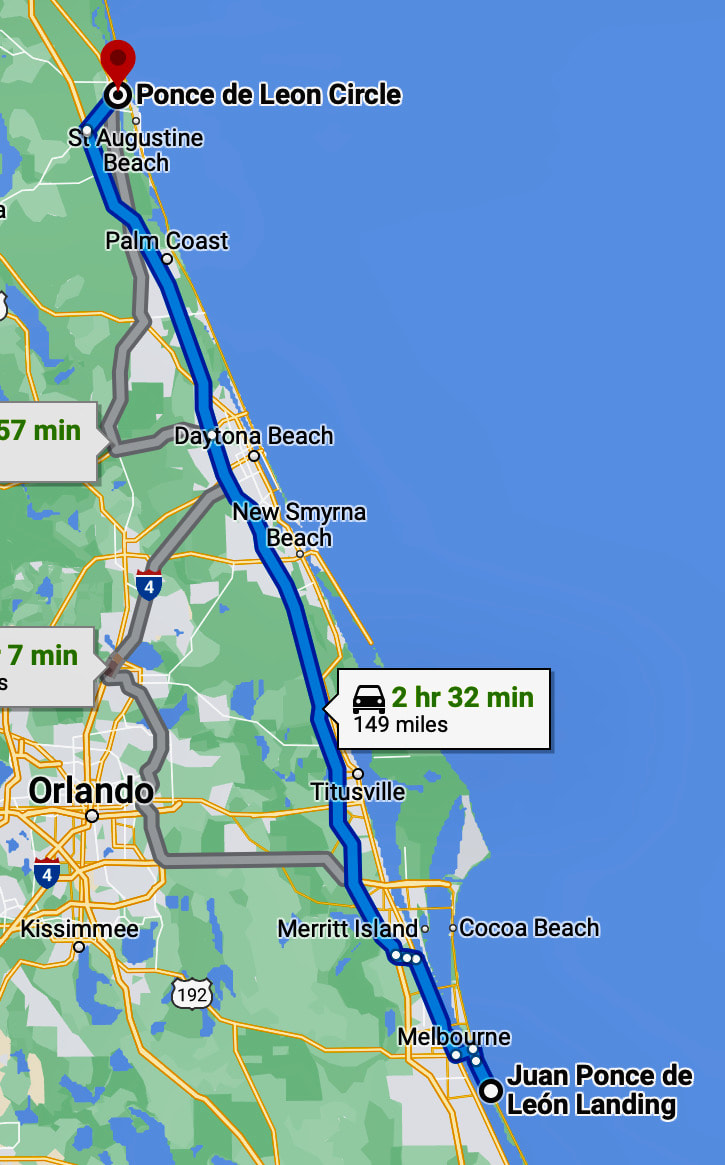

|

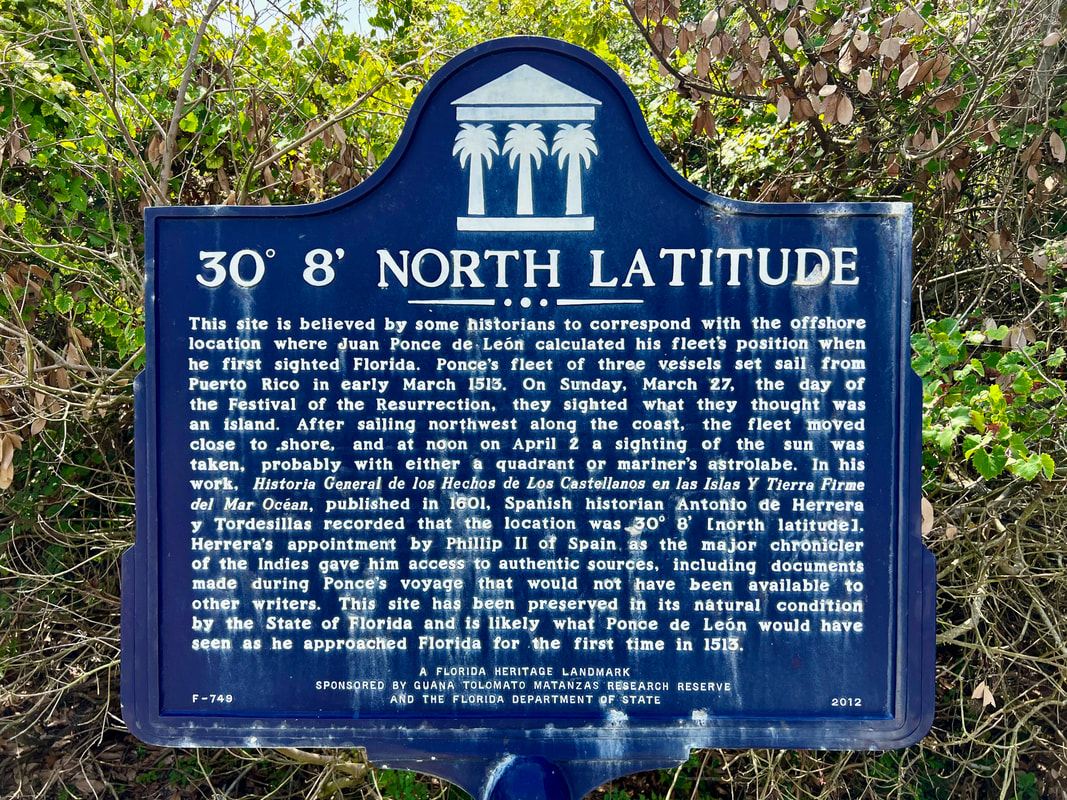

So let's hope that omitting our early Hispanic history is not a prevailing problem at the Smithsonian. And let's give them time. After all this is a preliminary exhibit in a limited space. However, the new museum should be much more inclusive of the entire timeline of our history. In fact, it should have an entire gallery devoted to that first Spanish American century that began when Ponce de Leon landed in Florida in 1513.

|

|

For now, however, I have to say I was satisfied. I liked what I saw. Although falling short on our early history, with a limited space the PRESENTE exhibit displays a variety of photos and artifacts that truly illustrate the immense diversity of our Hispanic/Latino community, and it clearly tries to represent all our Latin American nationalities, which is not easy.

If I have any criticism, it's because I want to see more U.S. Hispanic history, in a bigger space and a lot sooner. |

|

But for now, I think this article - merged with the two I have previously written — A Long-Overdue Museum and Smithsonian Omits Hispanics in U.S. History Exhibit — is likely enough for me to write a chapter in my book. Potential chapter title: "The Smithsonian and Hispanics/Latinos: From Willful Neglect to Mucha Paciencia." What do you think?

|

|

|

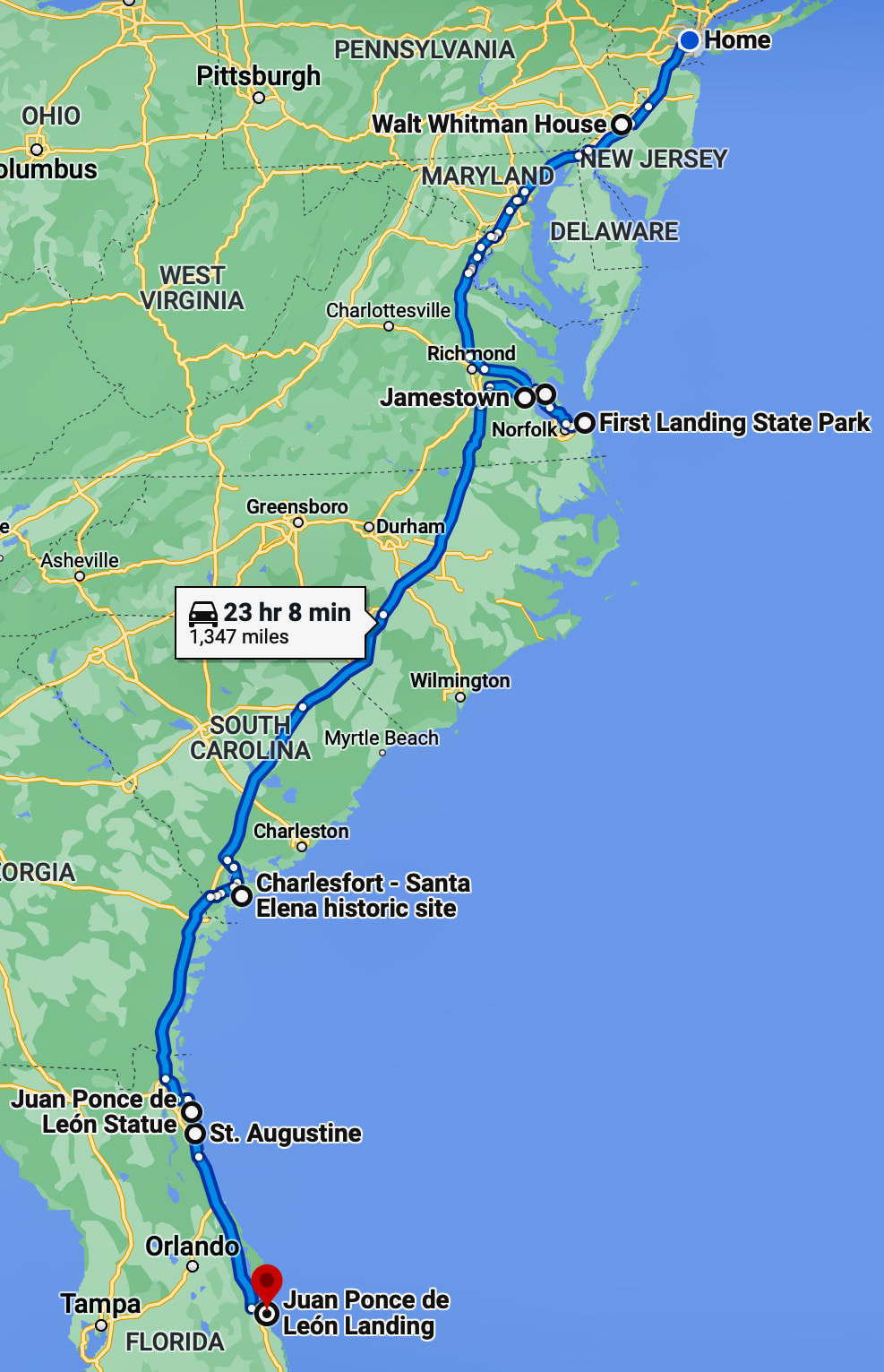

This is the last of 40 reports from my recent 3,728-mile road trip to visit Hispanic heritage sites across 10 states. Some will help to update and enhance some of the existing chapters in this website and others will become new chapters. Did you follow my reports? Do you know someone who would like to read them in Spanish? In a few days, I will begin posting them again, en español, in the same order as they were originally posted in English. Will you help me by sharing them with your friends?

´Gracias! |

39th stop: Revisiting Don Quijote

|

|

This is why I needed to return. Although that tour guide apologized and explained that he meant to say Spanish instead of French, I needed to know that other tour guides were not misinforming people. I had to take that tour again!

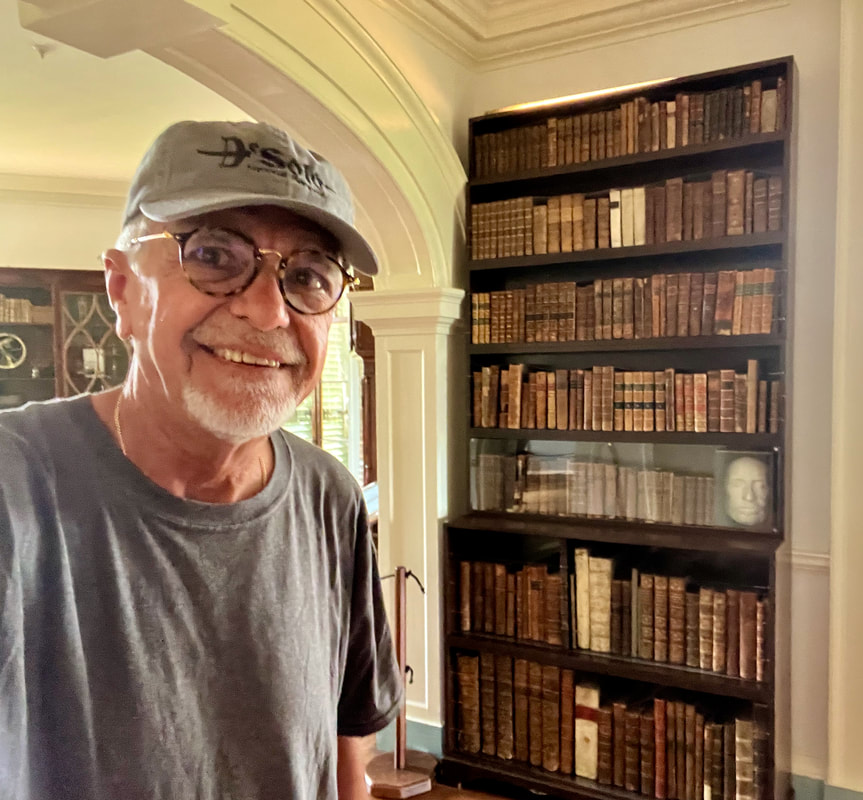

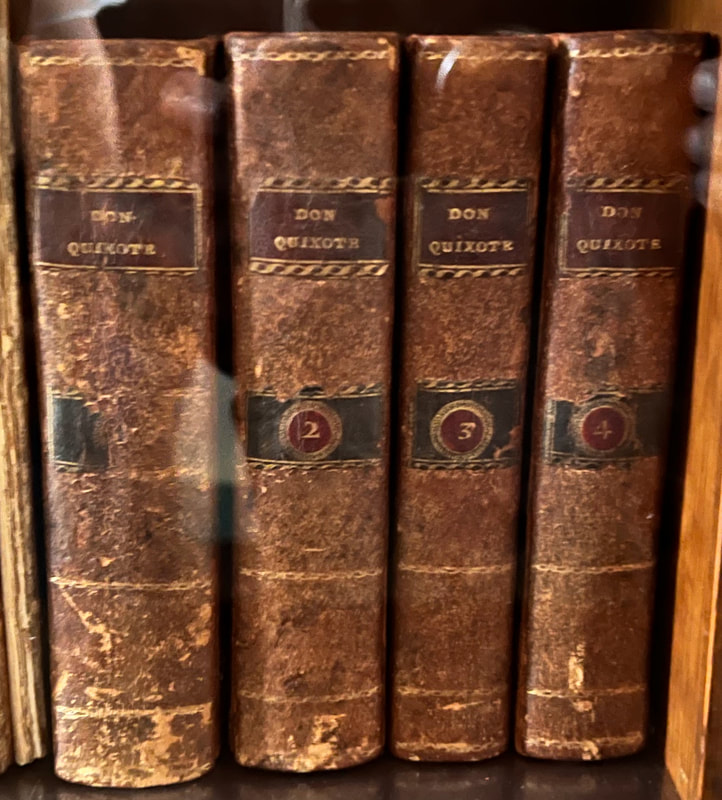

Much to my surprise, although no photos were allowed during my first visit (and I had to sneak a quick snap of Jefferson's books), this time we were told we could take as many photos as we wanted. Of course, shooting photos of anything in a glass enclosure is always a problem. You can't get rid of the reflections! Although most of Jefferson's books are in the Library of Congress, and although even most of the books on this shelve were not really his, the only the ones behind the glass-covered shelve were truly his books -- including a four-volume edition of Don Quijote.

Much to my delight, this time the guide knew that Spain's greatest novel is actually in Spanish! LOL She didn't even bring it up. I had to ask, "Where is Don Quijote?" But after pointing to a four-volume set, she recognized that it is written in Spanish. I felt relieved! "Actually, he taught himself Spanish with those books," I told the tour group, causing others to take a closer look and stick their heads in the way as I tried to take photos. LOL See my original report on my first visit to Jefferson's Spanish Library |

38th stop: Juan Pardo's Fort San Juan,

|

|

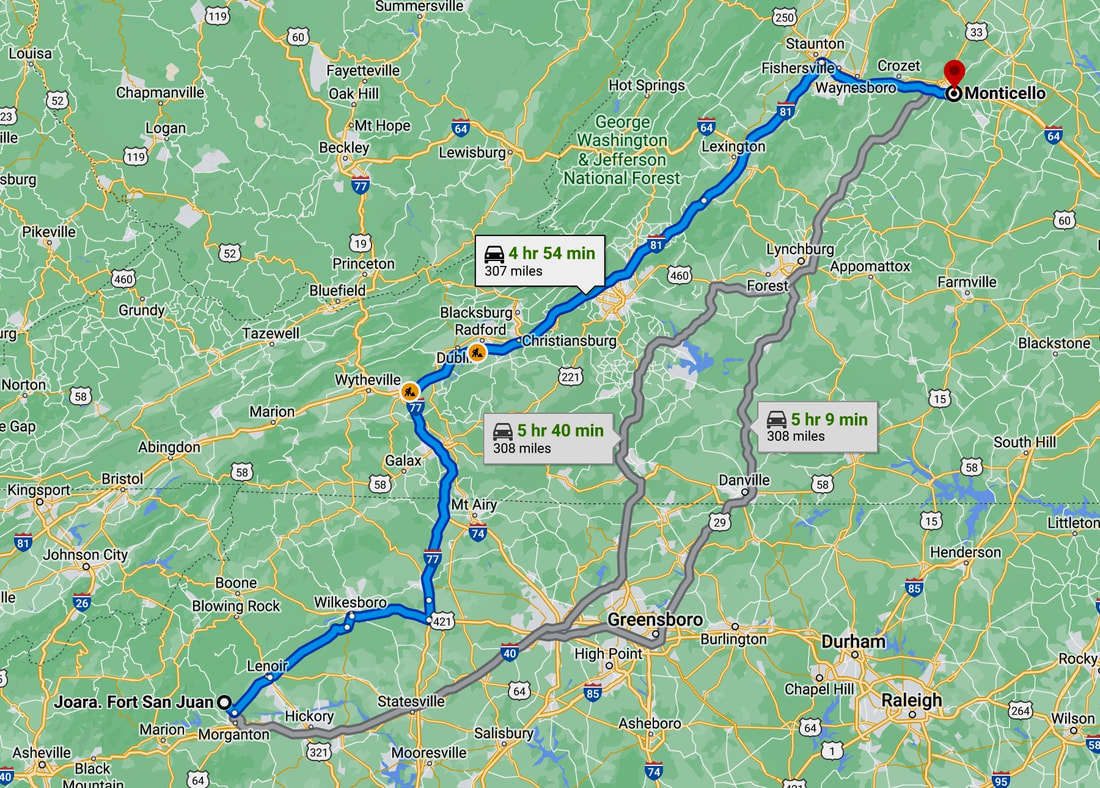

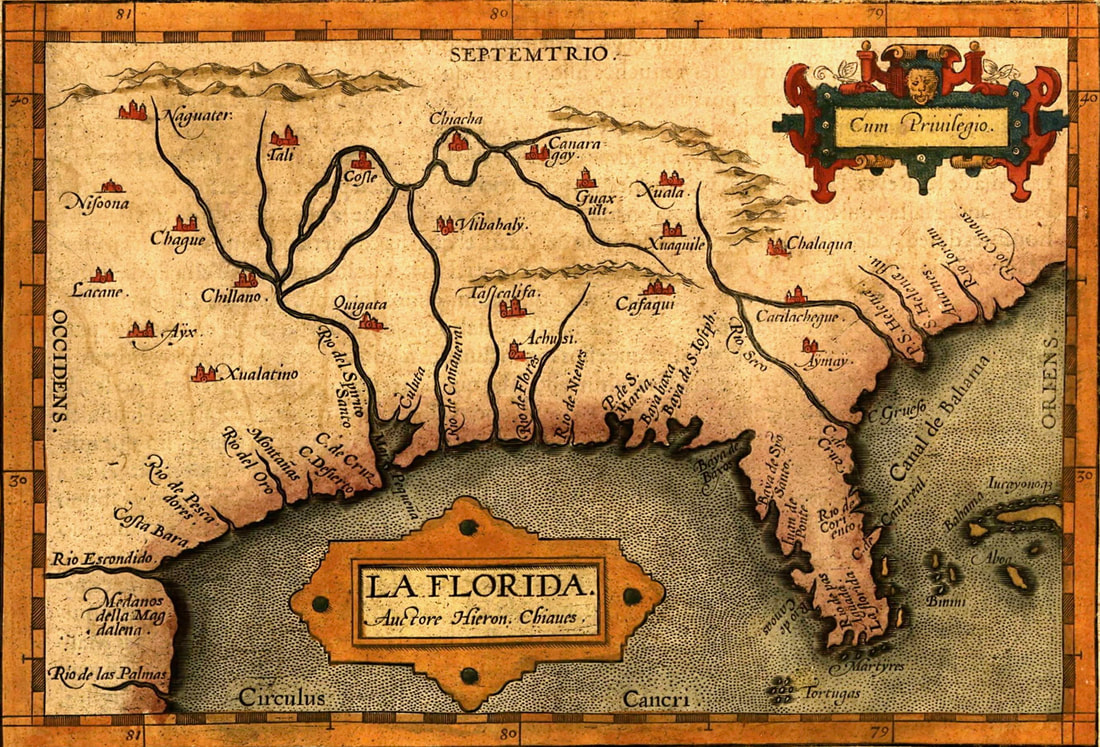

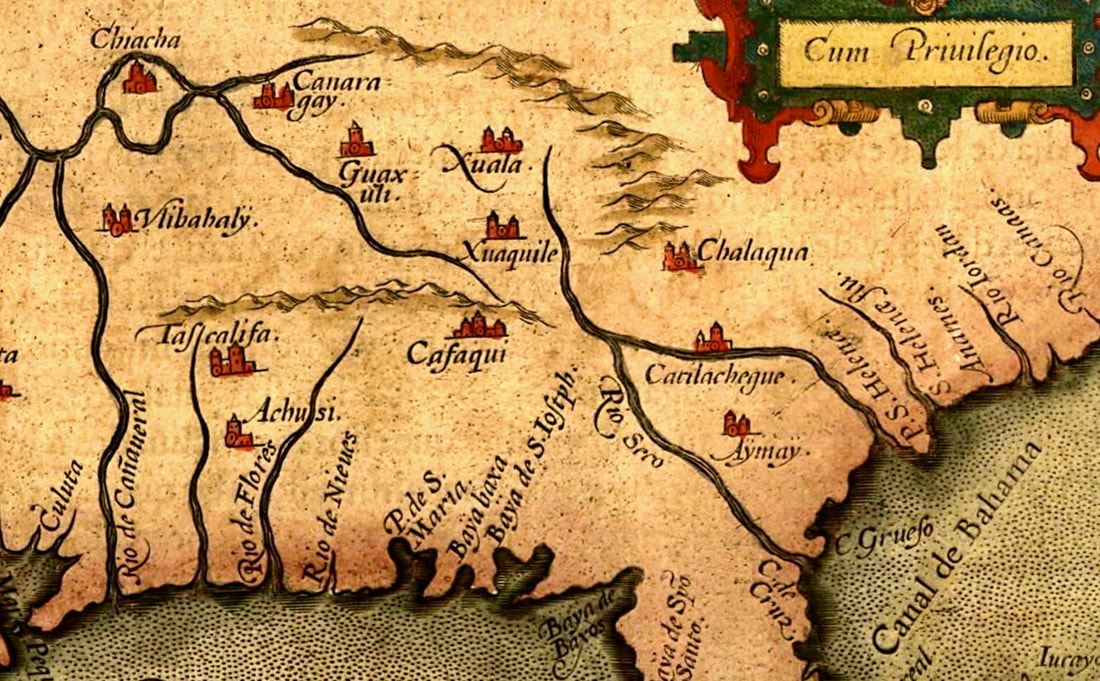

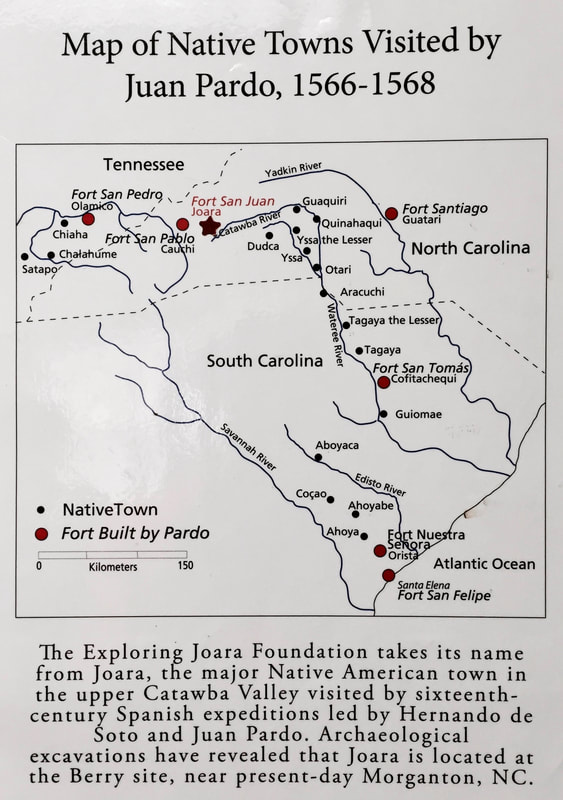

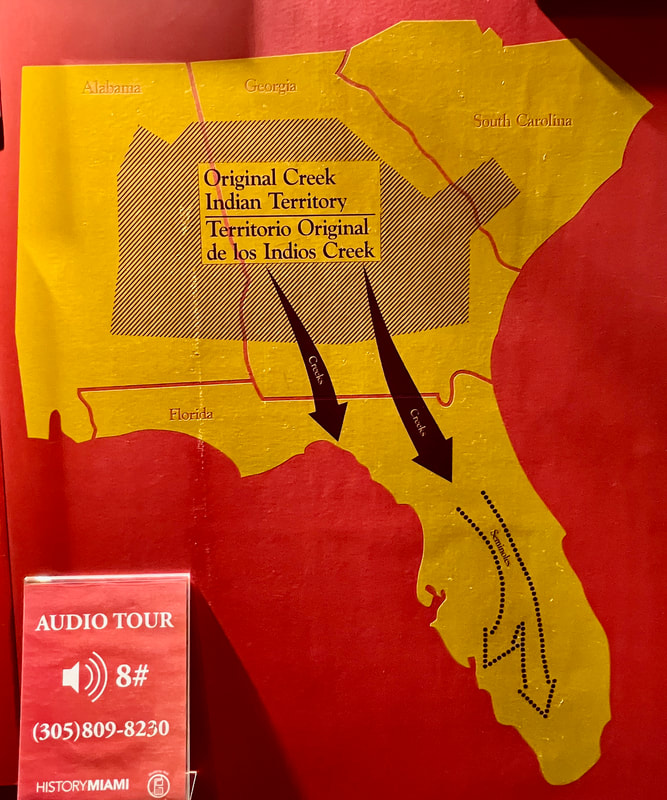

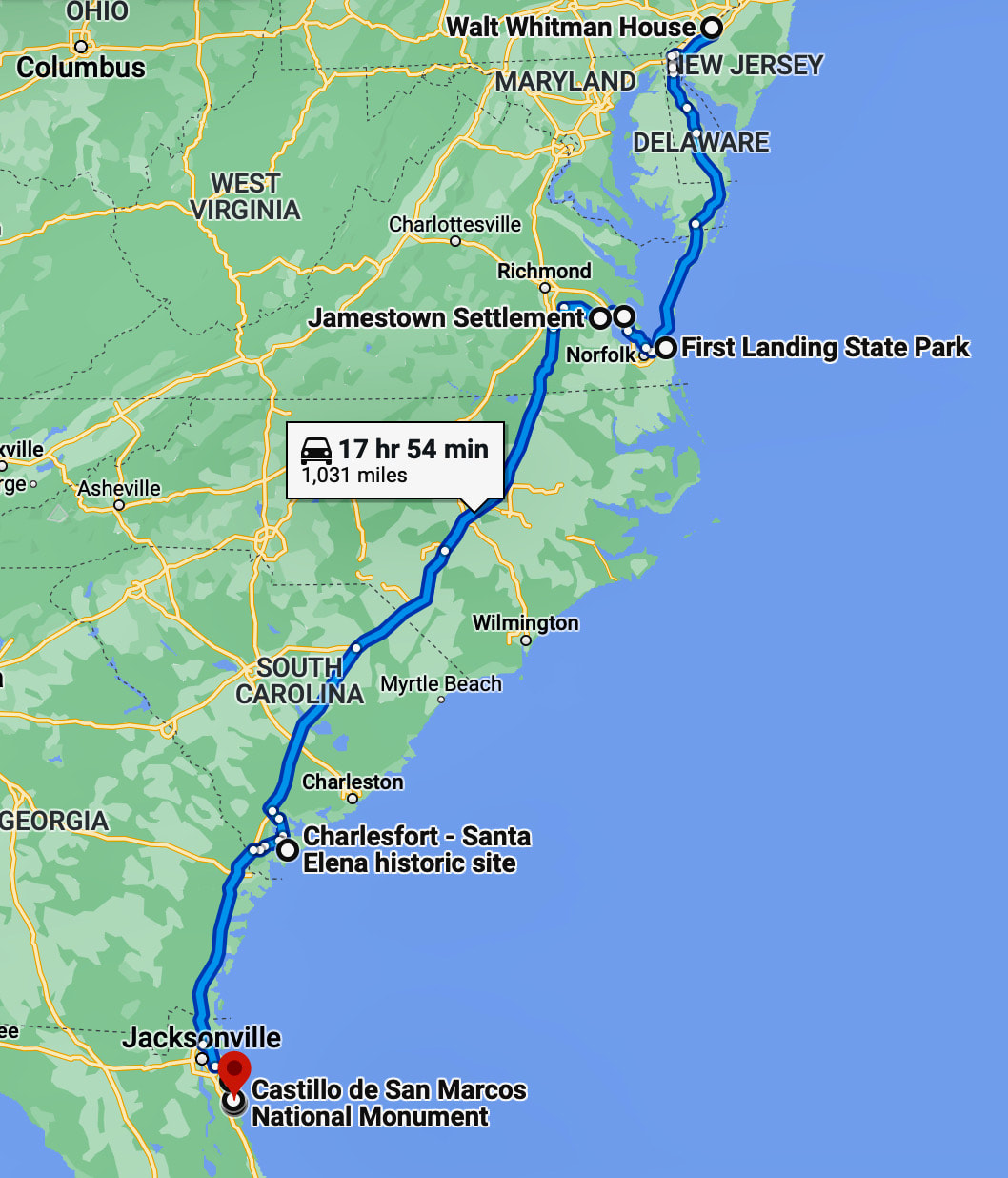

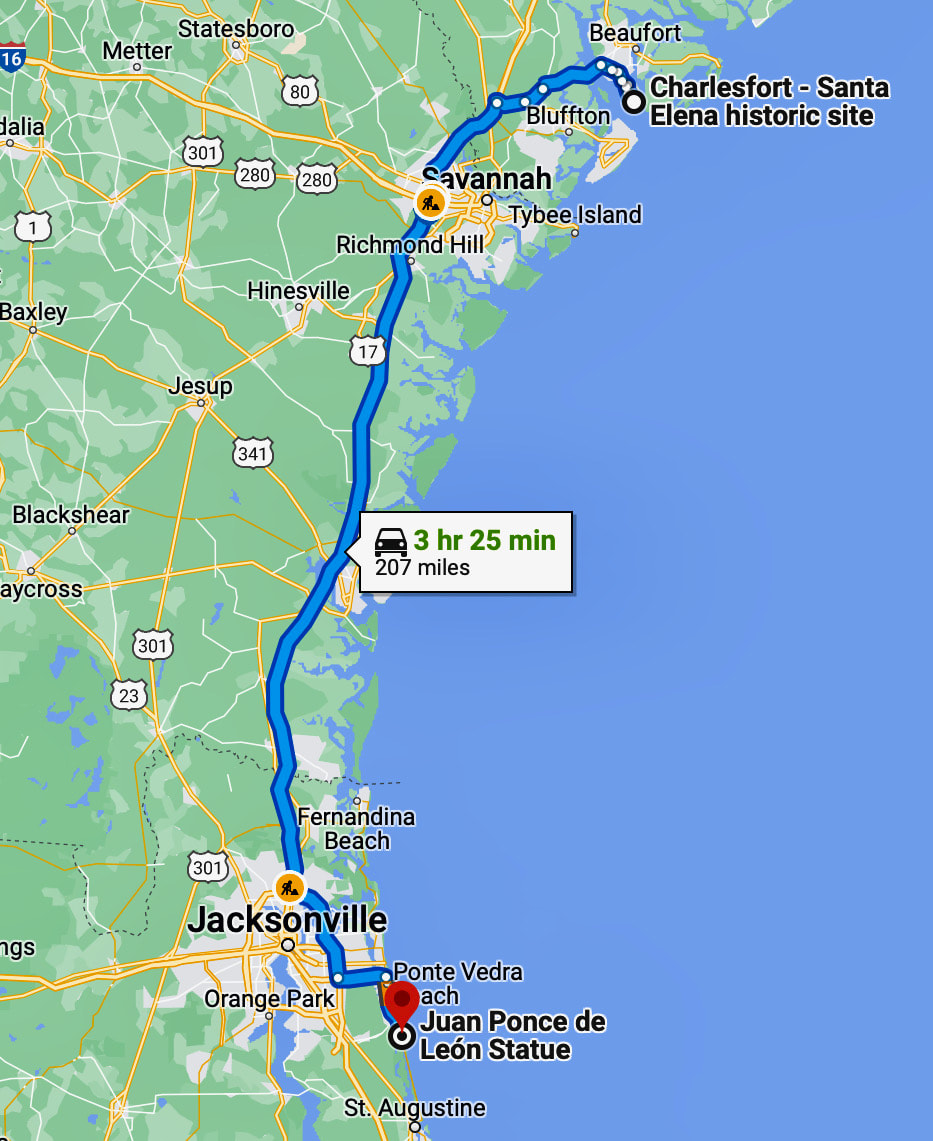

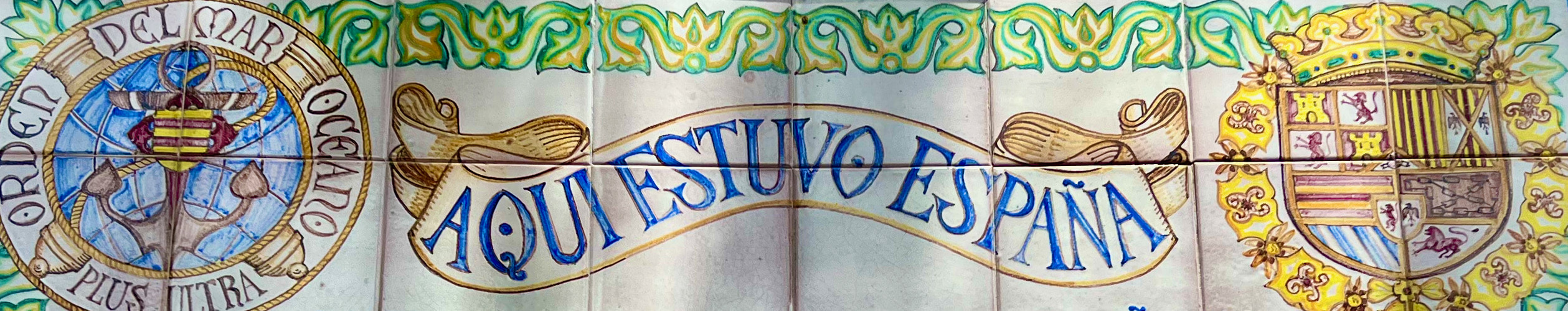

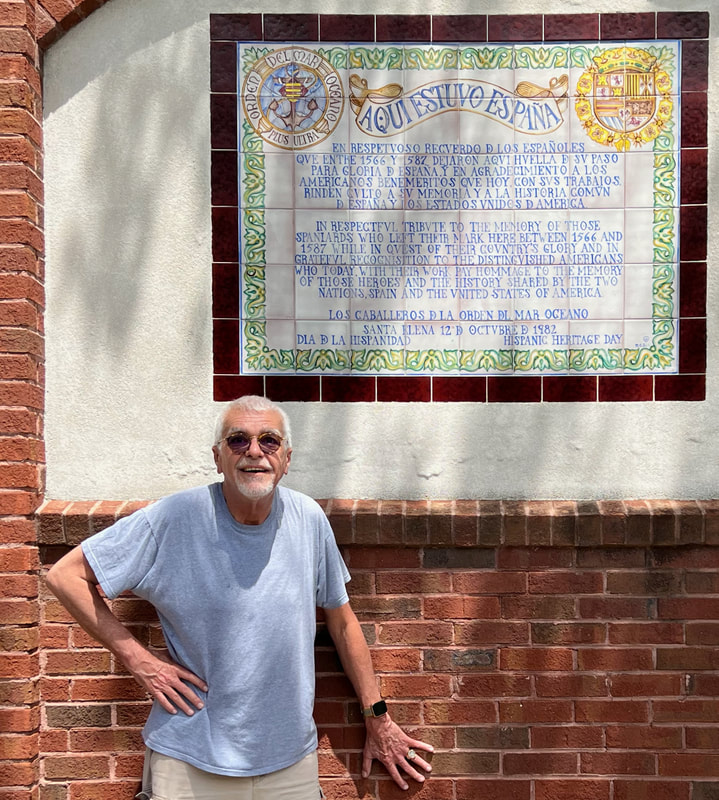

Santa Helena was the second major settlement established by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, the governor of Florida and founder of St. Augustine. At that time "La Florida" extended all the way north to the Carolinas and all the way west to Texas (see map), and Santa Elena was established in 1566 to spearhead further Spanish expeditions into the interior of North America. It was Menendez de Aviles who ordered Captain Pardo to explore the interior 0f "La Florida."

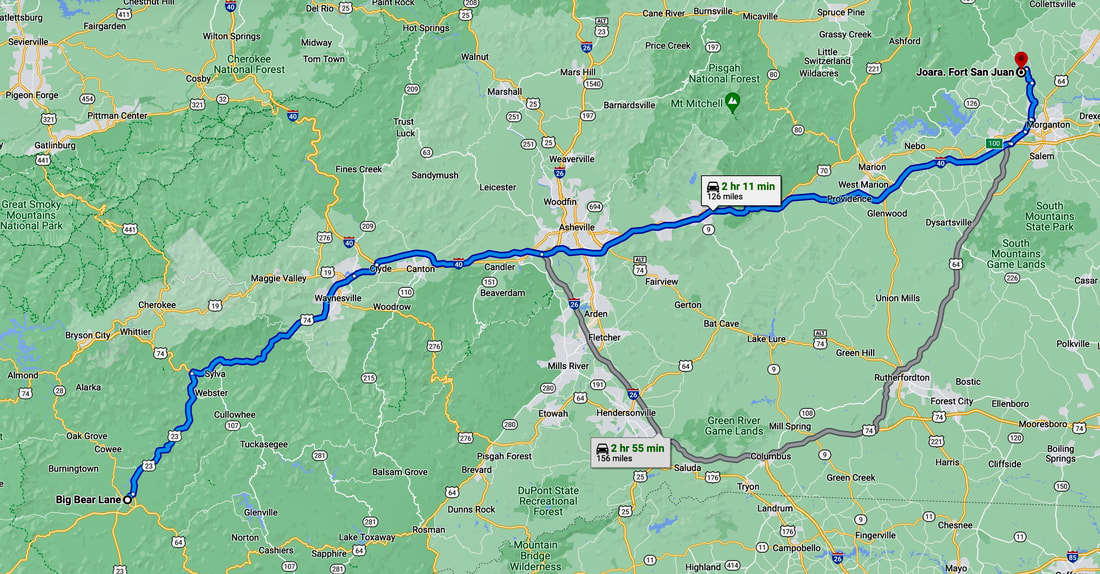

Pardo led two expeditions from Santa Elena, both on a northwesterly course across present-day South Carolina, North Carolina, and into Tennessee. He was looking to expand the Spanish empire into the interior, create trade with natives to relieve food shortages in Santa Elena, convert the natives to Christianity, and establish a route all the way to the Spanish silver mines of Zacatecas, in present-day Mexico. On the first expedition, starting on Dec. 1, 1566, he led 125 men until he reached Joara, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which the Spanish spelled "Xuala" on their maps (see images on this page). He built a good rapport and became an ally of Mico Joara, the village ruler, and with other village chiefs in present-day North Carolina. But they where slowed by a heavy snowfall and decided to build Fort San Juan, a blockhouse structure, near Joara. After a couple of weeks, Pardo garrisoned the fort with 30 men under the command of Sergeant Hernando Moyano de Morales and continued his exploration until returning to Santa Elena in March of 1567. |

|

However, the Spanish alliance with some Indian chiefs got them involved in fights with others. Siding with Mico Joara meant war against his enemies. And so, with the help of Sergeant Moyano and some 15 Spanish soldiers, Mico attacked and defeated the Chisca natives in present-day Saltville, Va.

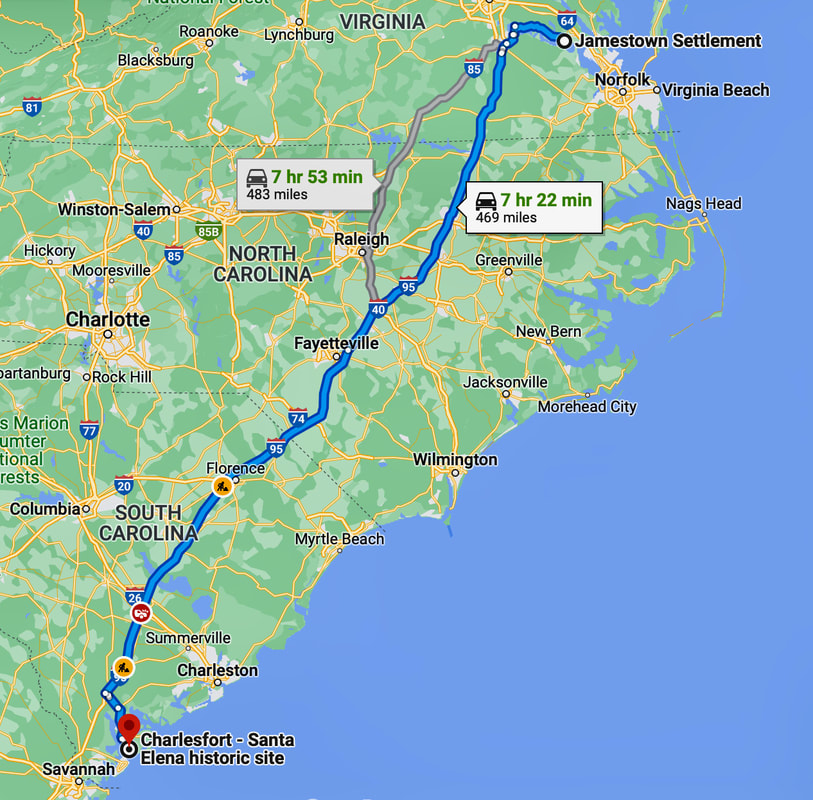

Yet, on his second expedition, when Pardo returned to Fort San Juan in September of 1567, he was told that Moyano and most of his men were in Chiacha, a native village near present-day Dandridge, in northeast Tennessee, where they were surrounded by Chiahan Indians and confined to a small fort they had built there. Pardo, arriving with 120 additional soldiers, was able to retrieve Moyano and his men back to Fort San Juan, where he again left a garrison of soldiers and moved on to establish more forts, always leaving a small contingent of Spanish soldiers and Jesuit missionaries at each one. He and his men built six forts — the first European settlements in South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee, predating the earliest British settlement at Roanoke Island, N.C. by 18 years. The forts were meant to furnish supplies along the land route to Zacatecas. |

|

However, while Pardo was back in Santa Elena, to resist French attacks there, the natives resisted his interior settlements. They attacked and burned the forts, and within 18 months, killed all but one of the 120 soldiers and missionaries Pardo had left behind. Pardo never returned to the interior. That was the last time the Spanish tried establish a trail to Zacatecas, or to impose their colonial claim in the interior of the continent. Some 18 years later, British efforts to build the Roanoke Colony, on the east coast of North Carolina, in 1585 and 1587 also met strong native resistance and failed. Several decades passed before British colonists finally settled in this area.

|

|

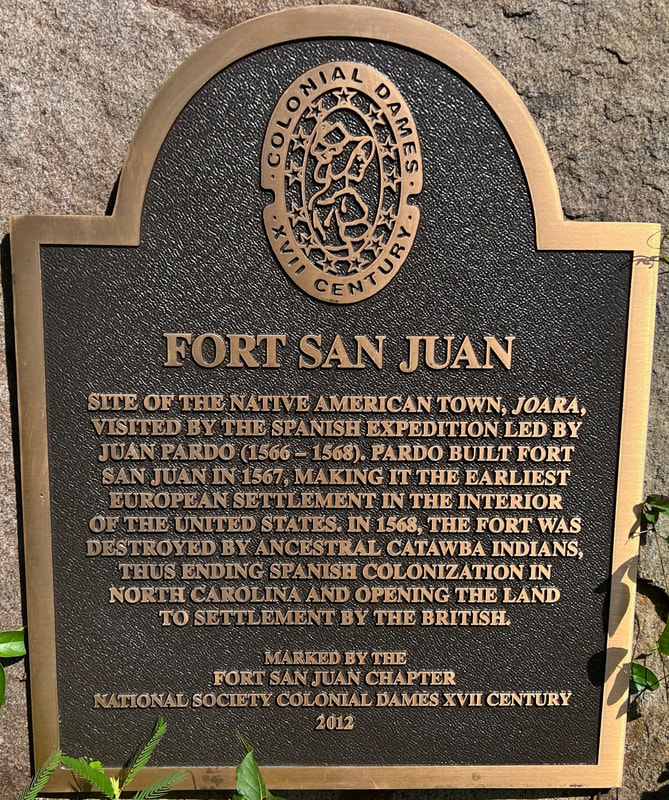

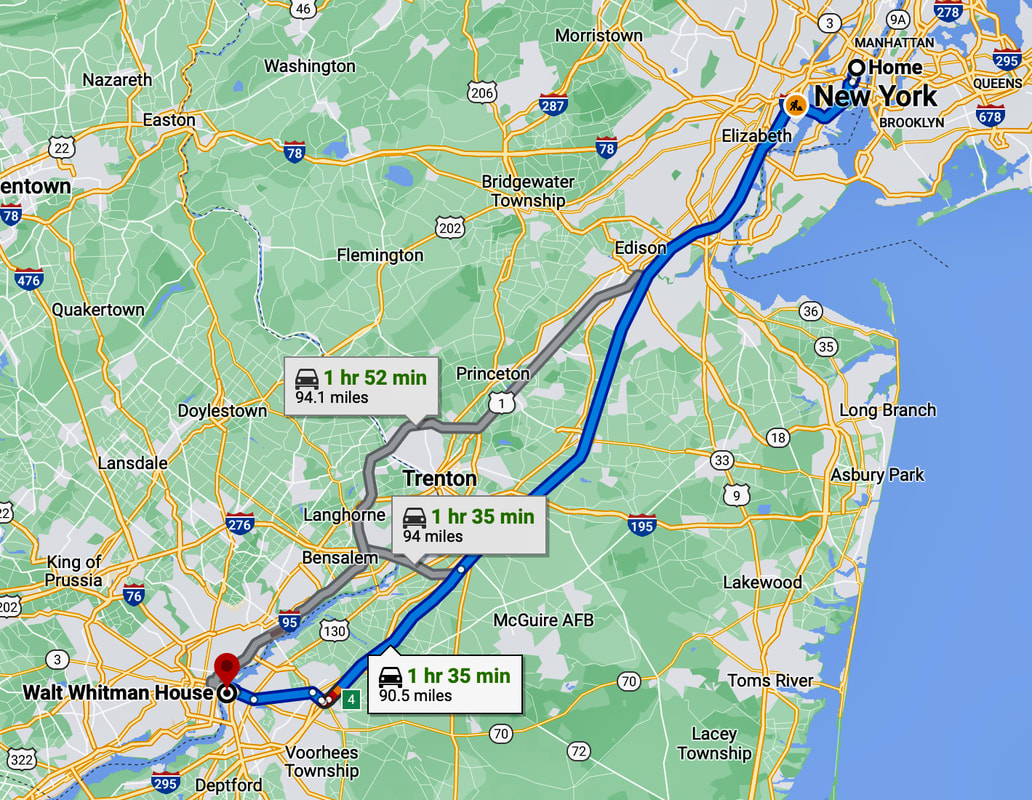

Although Joara's and Fort San Juan's exact location had been lost for centuries and disputed for many years, in 2009, while still unsure of the fort's exact location, the State of North Carolina erected a very visible, white, "Fort San Juan" historical marker in Morganton. This was based on earlier archaeological work that had revealed Spanish trade goods and tools suggestive of a Spanish settlement. The historical marker still stands on State Highway 181 (North Green Street), at the intersection with Bost Road, in Morganton (see photo).

|

|

The Joara/Fort San Juan location was finally confirmed at the Berry archeological site, eight miles north of Morganton, in July on 2013, when archeologists from three universities announced that they had definitive evidence proving that they found Joara's Mississippian artifacts and Fort San Juan — from its aged remains to its defensive moat.

And their admirable work continues today, through the non-profit Exploring Joara Foundation, an organization which administers research excavations at Joara and Fort San Juan. They have a variety of community and education programs, including "dig days" for students and the general public. I have been here before, and this is the second time I miss one of their "dig days," but I want to come back to get my hands dirty! |

|

"Our story is literally changing history books," says the Foundation on its website. "Did you know that nearly 20 years before The Lost Colony, 40 years before Jamestown, and 53 years before the Mayflower landed in Plymouth, the Spaniard Juan Pardo had built a series of six forts from the coast of South Carolina into the mountains of east Tennessee?"

Well yeah, now we do! Check out their YouTube video. They are literally digging for our Hispanic roots! Next Stop: Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. "So what does Jefferson's house have to do with our Hispanic heritage? you ask. "Why are we going there?" That's easy. I have been there before, and there is something I must go back to investigate. Check out: Jefferson's Spanish Library |

|

37th stop: Following De Soto's Trail

|

|

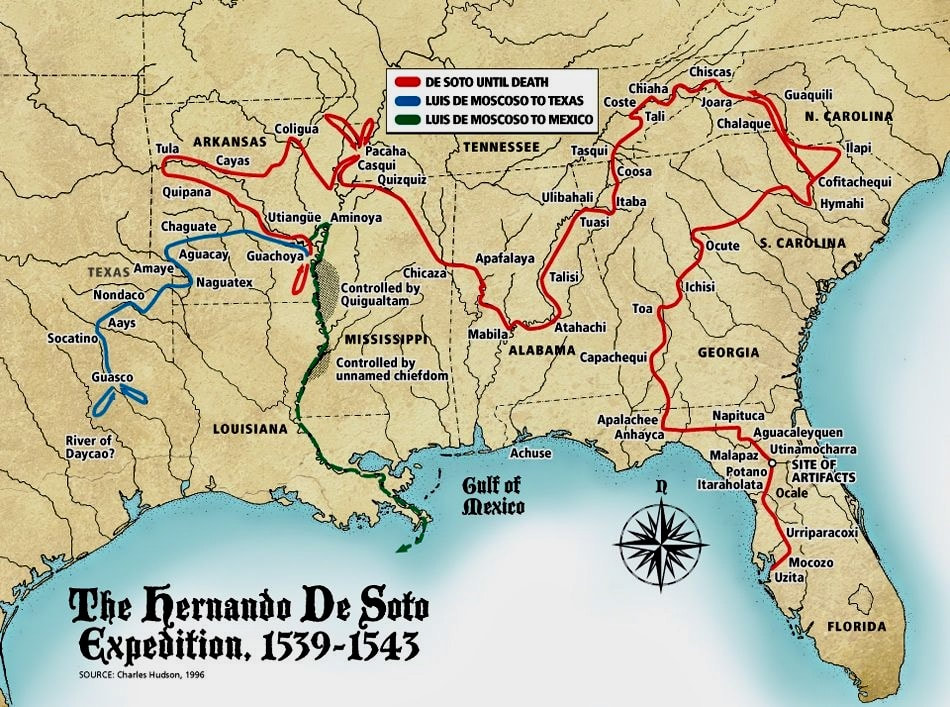

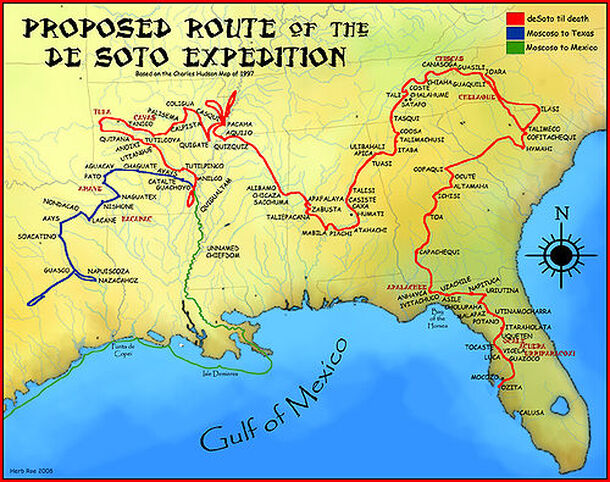

Here in western North Carolina, a part of the country where four current U.S. states nearly meet — Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee — the De Soto expedition went as far northeast at the village of Joara (near present-day Morganton, N.C.), then changed course and began heading southwest across portions of Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana, until they found the Mississippi River.

Their journey took four years and 4,000 miles, wiggling across today's U.S. map from Tampa Bay to Mexico. But the expedition lost its leader and will to keep exploring when De Soto died of a fever and was buried in the Mississippi River in May of 1542. Dodging attacks by natives, the survivors made their way to Mexico, where they knew they could hook up with other Spaniards. Of some 600 who started this journey, some 300 survived. |

|

But when the expedition was here and crossed the Little Tennessee River in western North Carolina, De Soto was already leading them back in a southwestern direction.

Nevertheless, I say we should keep going north to Joara. After all, some 27 years after De Soto was there, other Spanish explorers built a fort there. Let's go! |

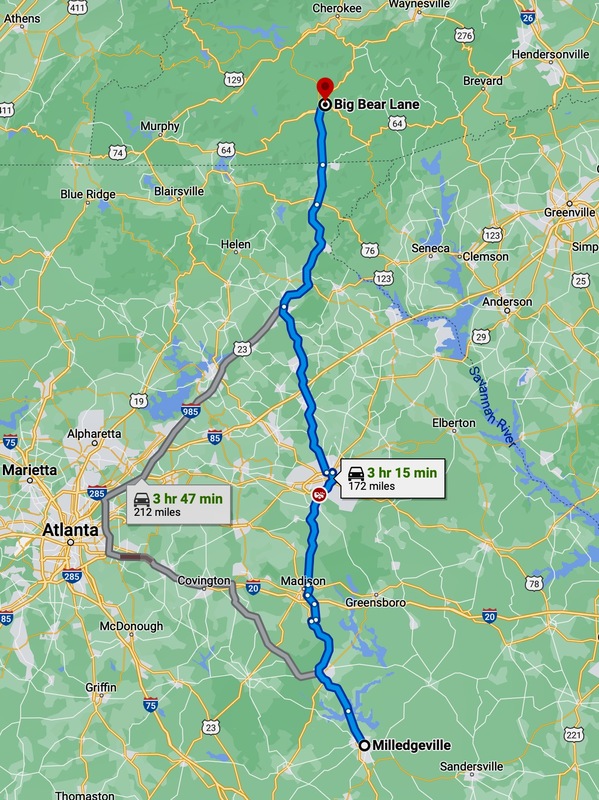

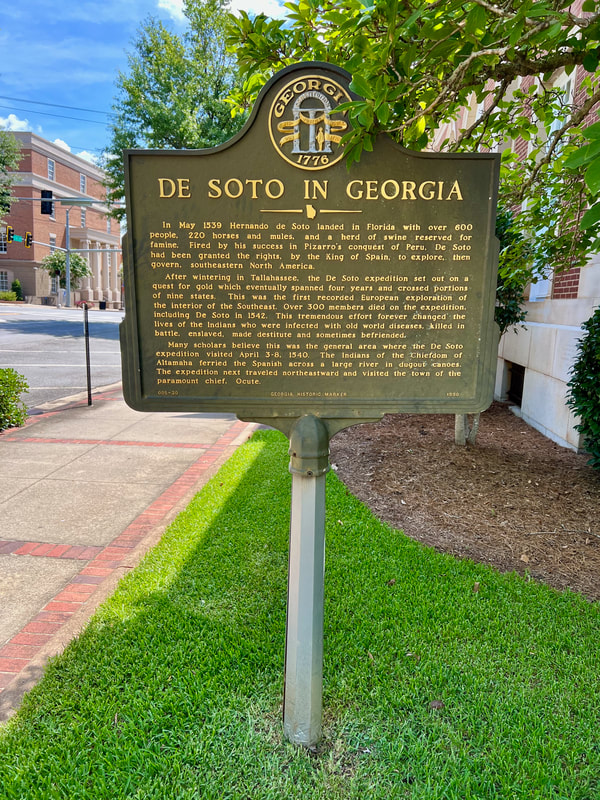

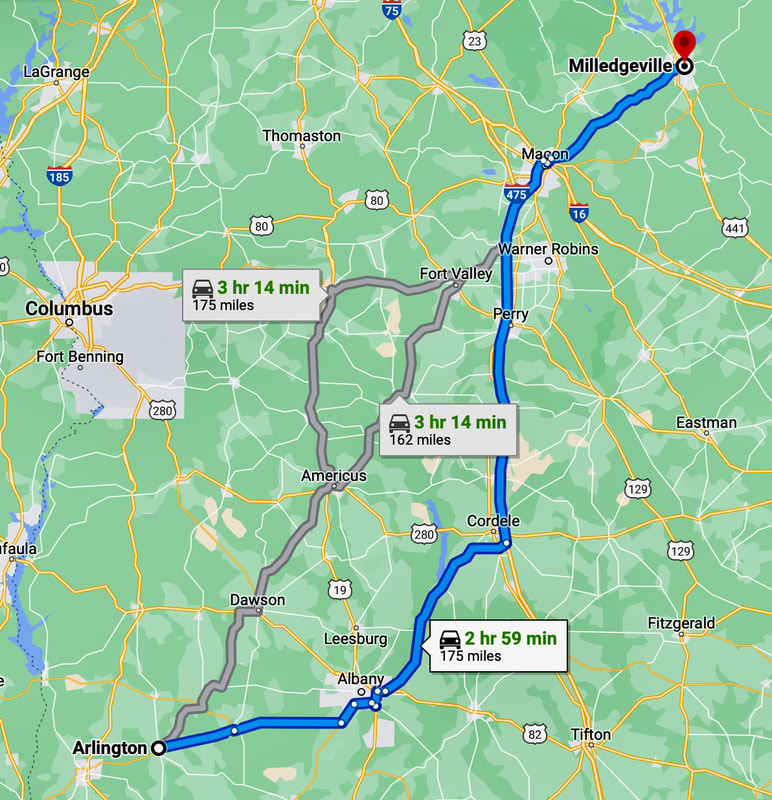

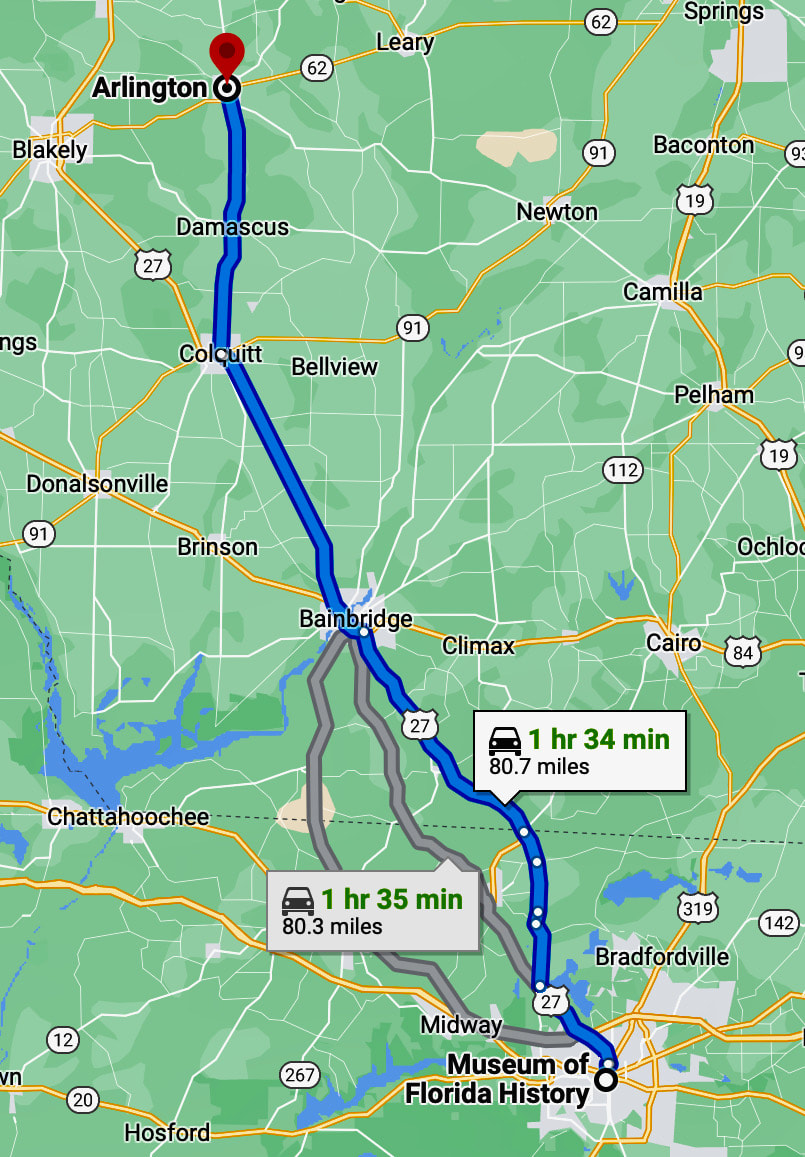

36th stop: Following the Trail of Conquistadors in Milledgeville, Ga.Some 175 miles north of Arlington, Ga., where we found a historical marker for the Hernando de Soto expedition, another Georgia town still recognizes their route. "Many scholars believe that this was the general area where the De Soto expedition visited April 3-8, 1540," says the historical marker in downtown Milledgeville, Ga.

"In May 1539 Hernando de Soto landed in Florida with over 600 people, 220 horses and mules, and a herd reserved for famine," the marker claims. "Fired by his success in Pizarro's conquest of Peru, De Soto had been granted the rights, by the King of Spain, to explore, then govern, southeastern North America." |

|

After spending the winter in the Tallahassee area, the expedition "set out on a quest for gold which eventually spanned four years and crossed portions of nine states," the marker says. While recognizing that "this tremendous effort" forever changed the lives of the Indians who were infected with old world disease or killed in battle, the marker also notes that "this was the first recorded European exploration of the interior of the Southeast" and that "over 300 members died on the expedition, including De Soto in 1542."

The marker also explains that the Indians of the Chiefdom of Altamaha "ferried the Spanish across a large river in dugout canoes" and traveled northeastward. And wouldn't you know it? That's the direction we are taking! We are not taking canoes, lol, but on this road trip we are following the trail of conquistadors! Are you coming? |

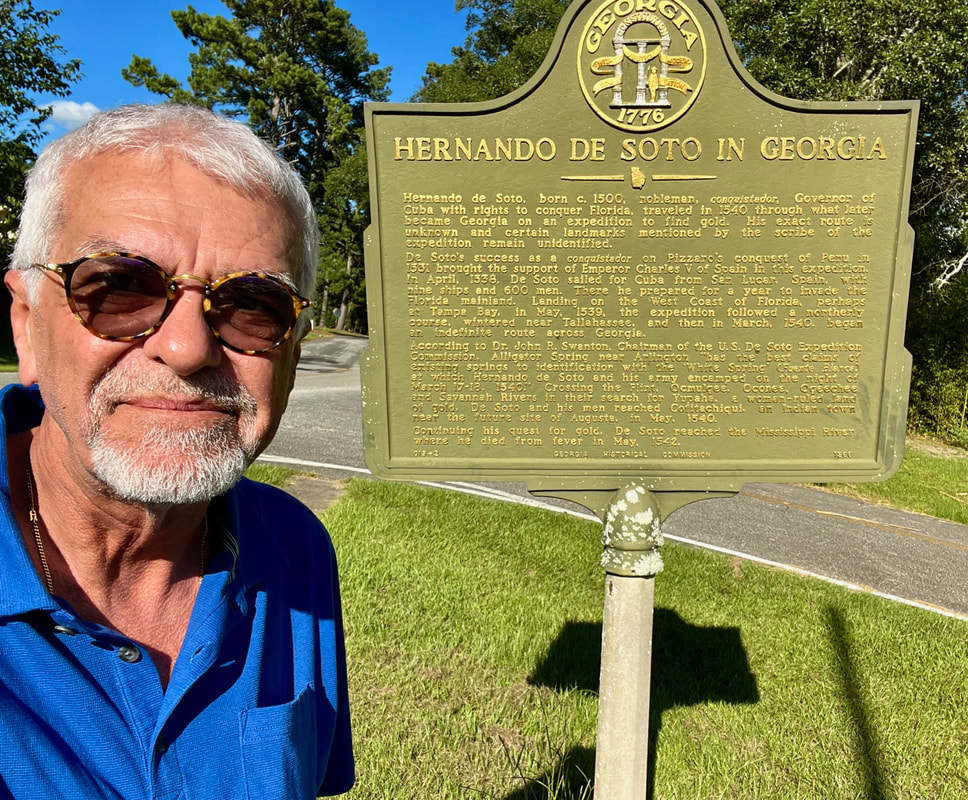

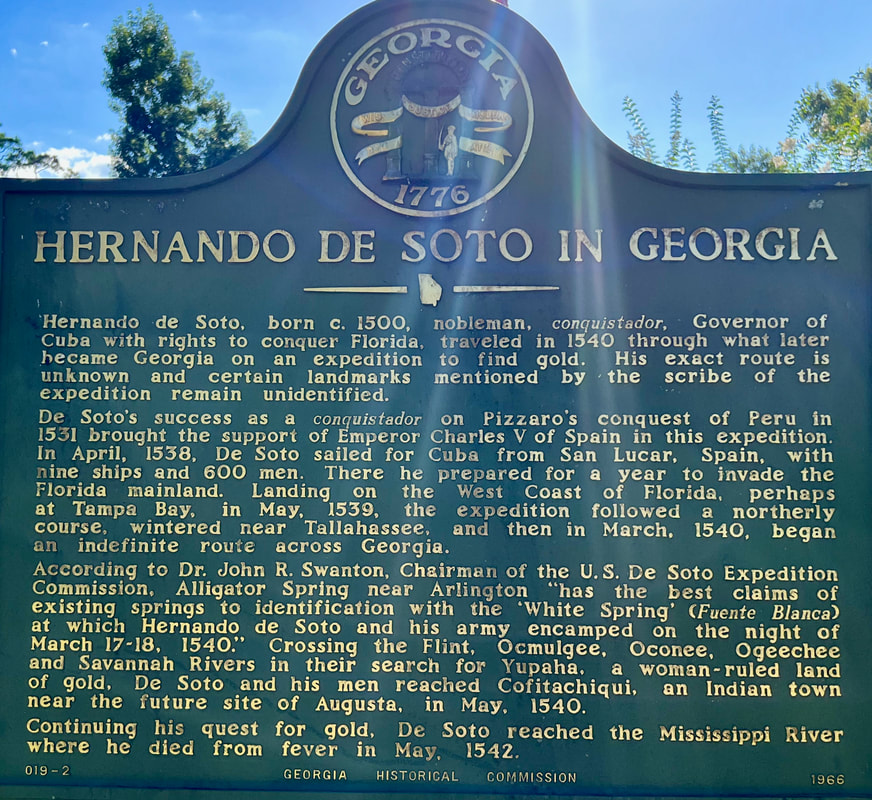

35th stop: Hernando de Soto

|

|

"His exact route is unknown and certain landmarks mentioned by the scribe of the expedition remain unidentified," the marker explains. Yet it also notes that Alligator Spring, near Arlington, “has the best claims of existing springs to identification with the ‘White Spring’ (Fuente Blanca) at which Hernando de Soto and his army encamped on the night of March 17-18, 1540.”

The De Soto expedition trekked across territory that later became Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana. Their four-year, 4,000-mile hike finally lost its drive when de Soto died of fever at the banks of the Mississippi River, where he was buried in May 1542. I don't intend to follow those footsteps, lol, but I say we should keep looking for historical markers on our way north! Are you coming? |

Before we leave Tallahassee

|

|

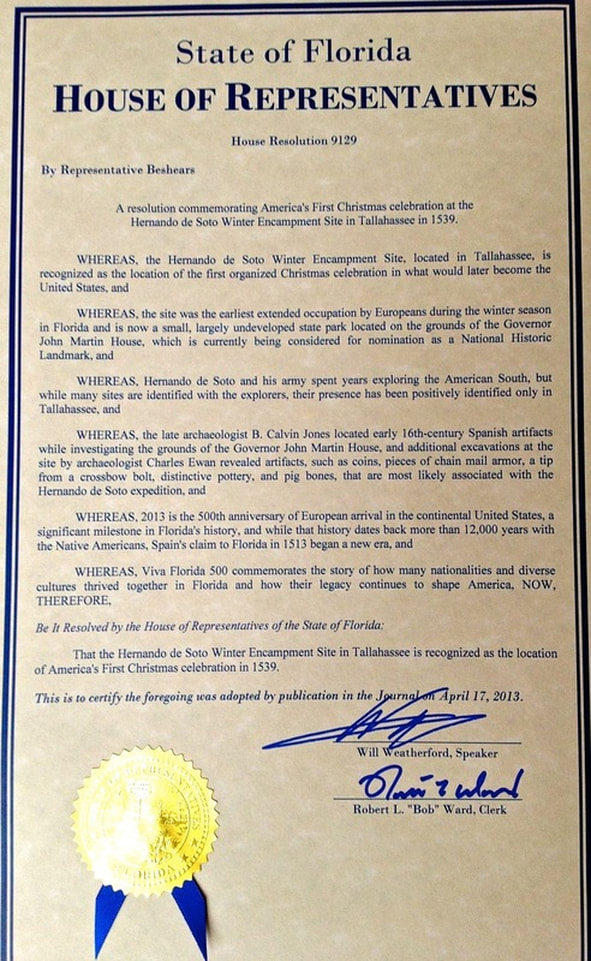

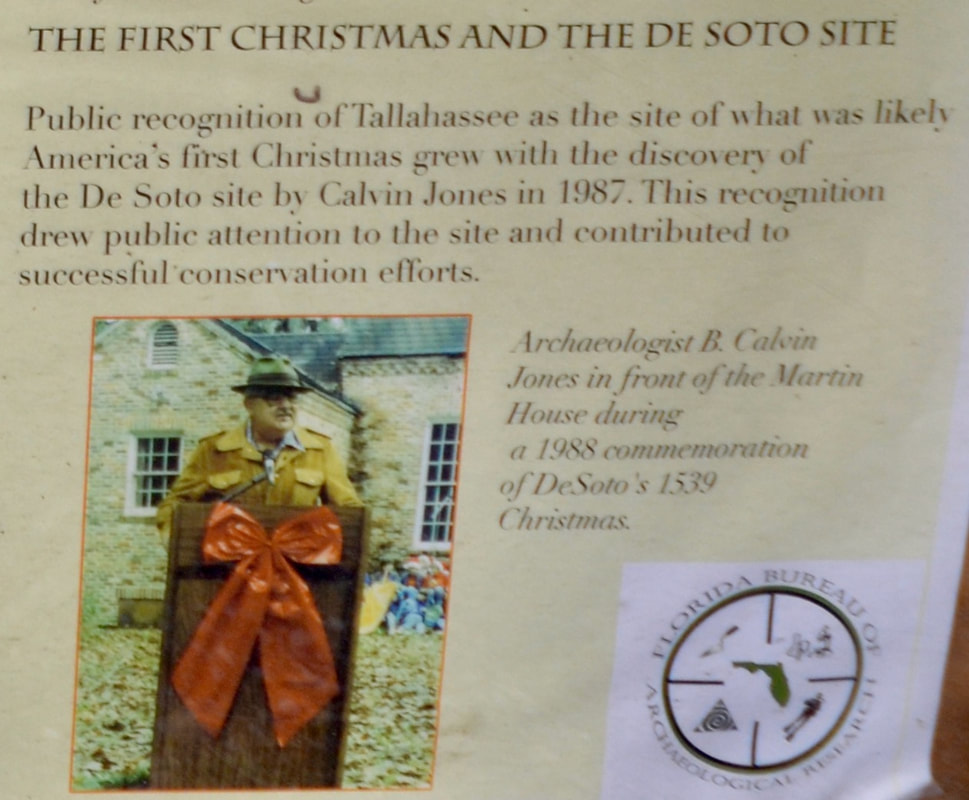

"The route of de Soto has always been uncertain, including the location of the village of Anhaica, the first winter encampment," a historical marker explains. "The place was thought to be in the vicinity of Tallahassee, but no physical evidence had ever been found. Calvin Jones' chance discovery of 16th century Spanish artifacts in 1987 settled the argument. Jones, a state archaeologist, led a team of amateurs and professionals in an excavation which recovered more than 40,000 artifacts . . . These finds provided the physical evidence of the 1539-40 winter encampment, the first confirmed De Soto site in North America."

|

|

After the Spanish took over Anhaica, which had been forcibly abandoned by its Apalachee natives, they were under constant attack by the Apalachees. According to the signs here, perhaps that is the reason why accounts of that portion of the expedition mostly detail those raids and fail to mention Christmas celebrations.

Yet historians believe that "the three priests who accompanied the De Soto expedition would have ensured that Christmas traditions were upheld," according to another sign titled "De Soto's Christmas in Tallahassee." The signs also explains that, "from this location the De Soto expedition traveled northward and westward making the first European contact with many native societies." We are not heading west folks, not on this road trip. But since we are heading north, I say we should follow De Soto's route, at least through Georgia and the Carolinas? Are you coming? |

To enlarge these images, click on them!

|

34th stop:

|

|

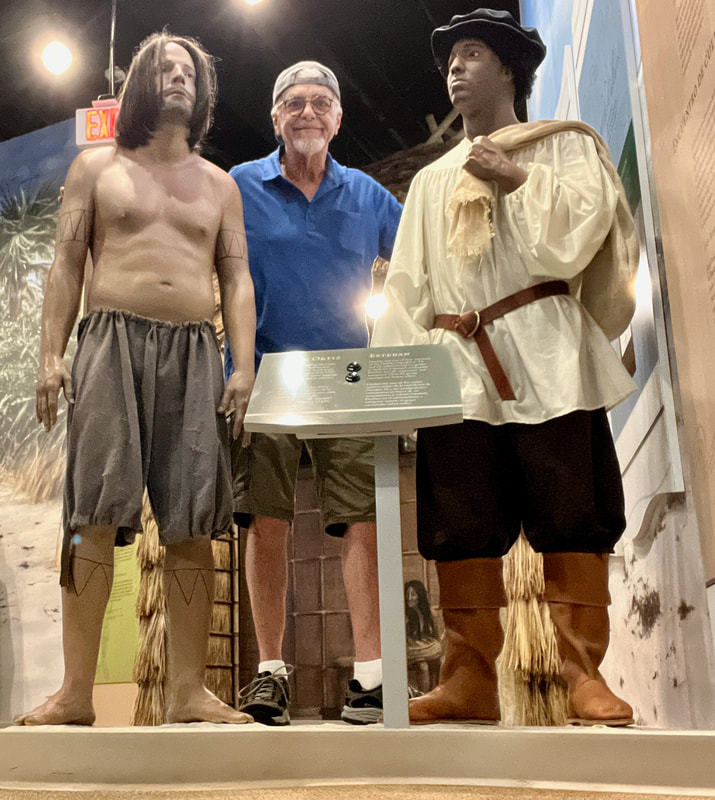

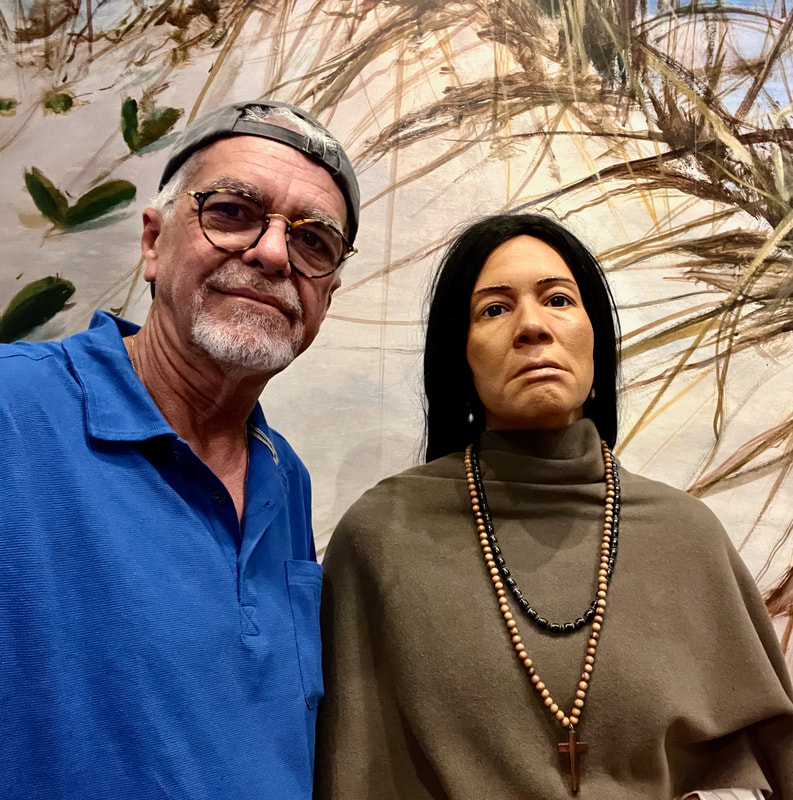

Once inside, of course, you are likely to be impressed over and over again. This museum is exceptional. It allows you to walk through the entire timeline of Florida history, with fascinating exhibits. I don't have the space to take you through all the history covered here, but I've been here before and made a few wax sculpture friends, so let me introduce you to them!

Two of them are standing together, Juan Ortiz and Estevanico, because they are both survivors of the 1528 Panfilo de Narváez expedition to Florida. Ortiz was captured by natives shortly after their arrival and lived among the Uzíta and Mocoso Indians near Tampa Bay for 11 years, until he hooked up with the Hernando de Soto expedition and, having learned the native languages and customs, became De Soto's guide and interpreter. Estevanico was a slave and one of four other Narváez expedition survivors who spent almost eight years to get from Tampa Bay to Mexico City — mostly on foot! |

|

I don't remember seeing Captain Francisco Menendez when I was here in 2014, but after visiting Fort Mose in our seventh stop a few weeks ago, I was glad to see the captain of the black Spanish militia and leader of Fort Mose recognized here. He deserves it! "Captain Menéndez played a crucial role in the establishment of the first legally-authorized free-black community in what is now the United States," the exhibit explains.

But let me introduce you to some of the others: • Ana Méndez, barely a teenager in 1539, pretended to be a young man to end up becoming one of two Spanish women with the Hernando de Soto expedition. She worked as a servant for one of the expedition members., and she was the only female survivor. • Fray Luis Cáncer de Barbastro, a Spanish priest and experienced missionary of the Dominican order, came to Florida in 1549 "to preach peacefully to the Indians" and became an advocate for humane treatment of the Florida natives. • Francisco Pellicer, born on the Spanish island of Menorca (Minorca), worked as a carpenter at New Smyrna, a large indigo plantation in East Florida where conditions were so harsh that surviving Minorcan settlers eventually abandoned the plantation. According to folks stories told by their descendants, it was Pellicer who (with Father Pedro Camps) led the settlers to St. Augustine. Do you remember that we covered "New Smyrna" in our 15th stop? • Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley, who was born in Senegal in West Africa, was captured and enslaved as girl. Zephaniah Kingsley, a plantation owner and slave trader, brought her to Florida. And yet according to this exhibit, "he later freed her, and she eventually managed her own land and enslaved blacks." • Saturiwa was a Timucuan chief in northeast Florida. "In 1564, the French, and later the Spaniards in 1565, established settlements within or near his chiefdom," the exhibit explains. • Cacica Doña Maria Meléndez was the Timucuan Indian woman chief of the Nombre de Dios Mission, near St. Augustine, in the late 1500s. She was a Christian who led one of the earliest mission villages established by Spain. Fascinating stuff, right? This museum has too much of it, lol, at least to report as part of this road trip. But I'm just getting started. My research and photos will undoubtedly produce many more chapters for this webpage, and a book-in-progress. So where are we going now? Where is our next stop? I say we should head north and pick up the trail of the De Soto expedition! Are you coming? |

|

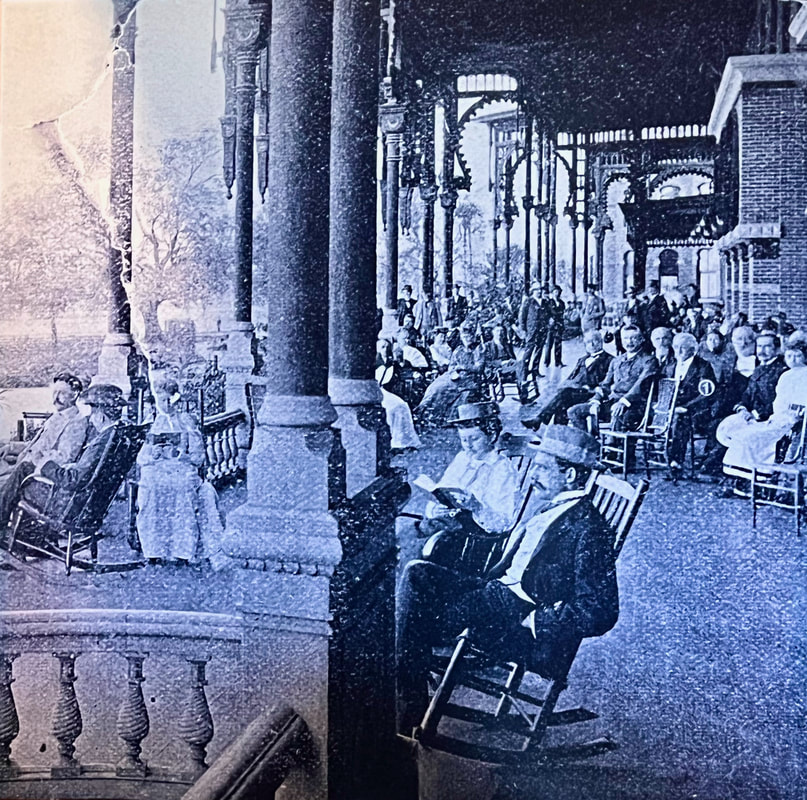

33rd stop: The Tampa Bay Hotel:

|

|

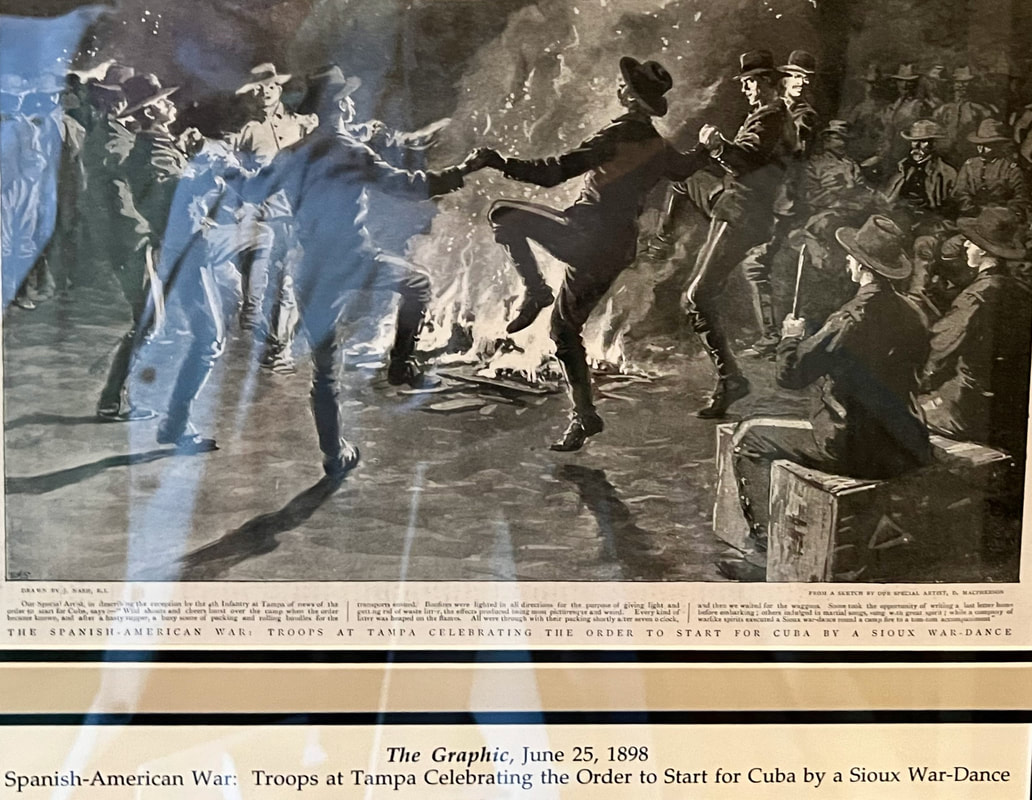

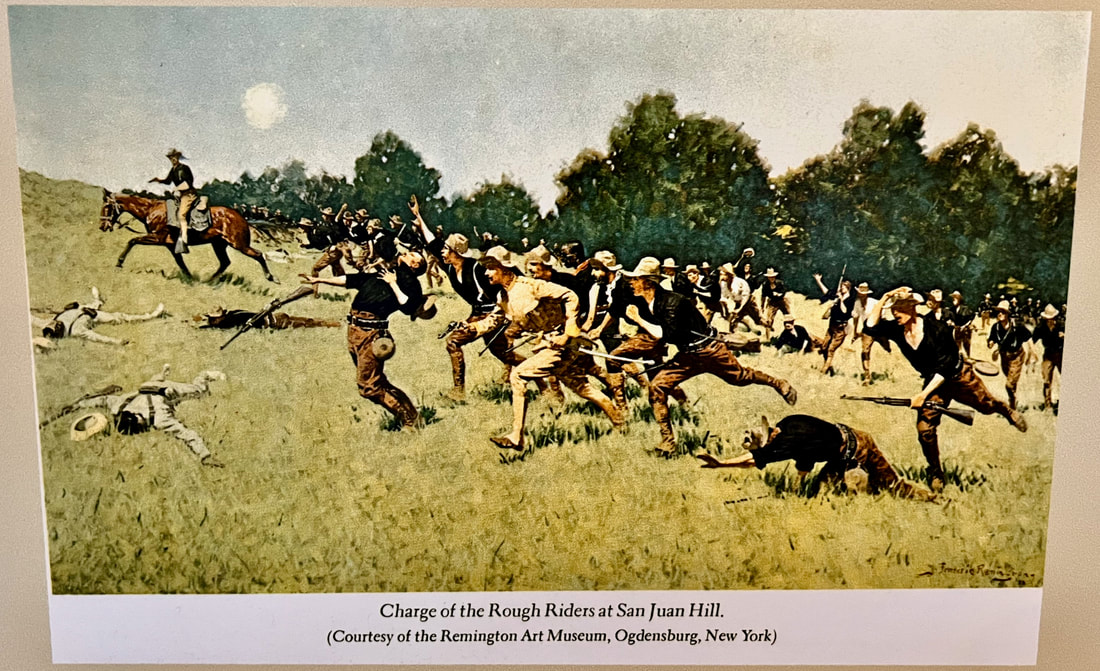

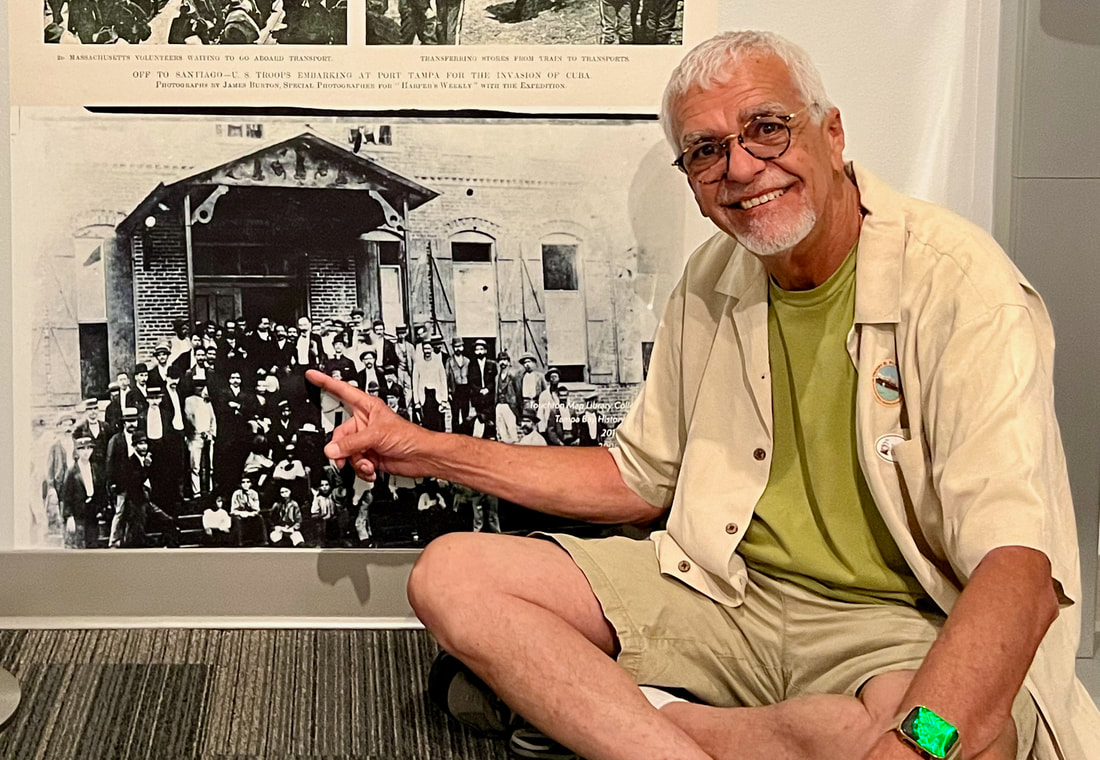

Other exhibits explain that the Army embarkation from Tampa was "chaotic" and "utterly mismanaged." Apparently, the soldiers were so anxious to get out of Tampa that they held celebrations, like the one illustrated in an exhibit image (see below) showing the soldiers dancing when they received orders to go to war.

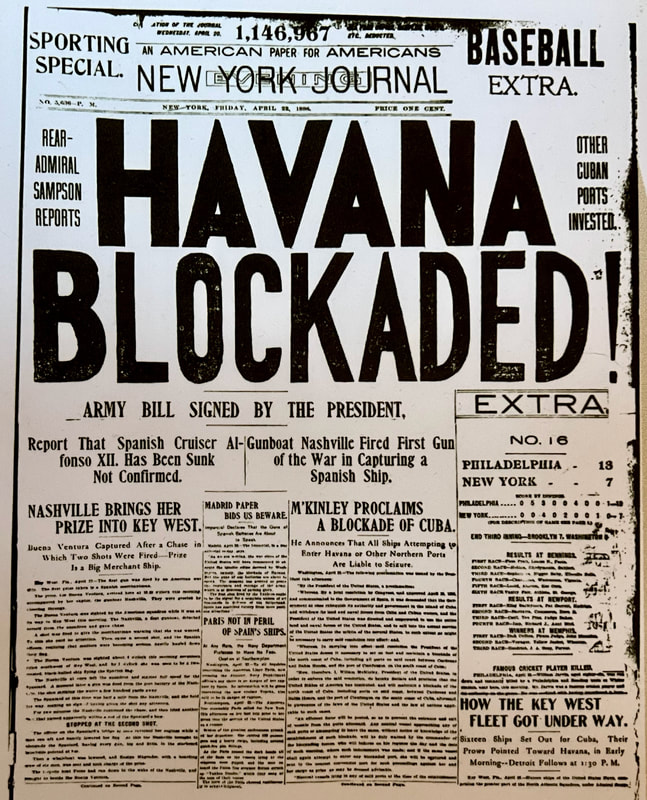

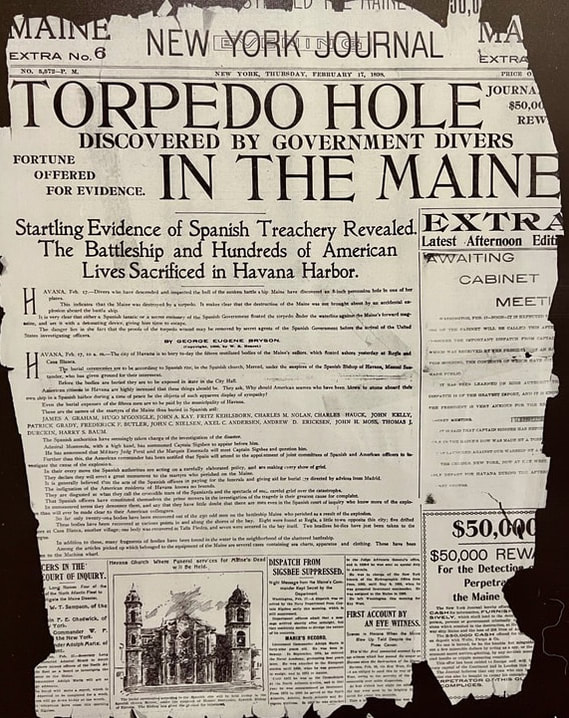

"In the end, the Americans were able to board only about 16,000 fighting men, along with 89 war correspondents and artists, 11 foreign military observers, 30 civilian clerks, 272 teamsters and 107 stevedores — the largest military expedition that had ever left the United States," an exhibit explains. Here you learn about all the factors that triggered the American involvement in the war, starting with the years-long struggle for Cuban independence and the involvement in that struggle of Tampa's Cuban cigar manufacturing community in the 1890s. Other exhibits tell you about "the ruthless and brutal measures the Spanish army resorted to in Cuba to put down insurgents," and the yellow journalism practiced by New York newspaper publisher William Randolf Hearst, who "day after day" reported on Spanish atrocities in Cuba, "both real and imagined." Hearst allegedly told his war correspondents, "You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war." |

|

With the American public already calling for war, thanks competing yellow journalists, the final straw that led to a naval blockade of Cuba and a declaration of war against Spain came after the battleship U.S.S. Maine mysteriously blew up in Havana Harbor, killing 266 of its 354 crew members on Feb. 15, 1898. The the identity of possible saboteurs is still being debated, but it sparked an anti-Spain frenzy and gave the United States an apparently credible reason to go to war.

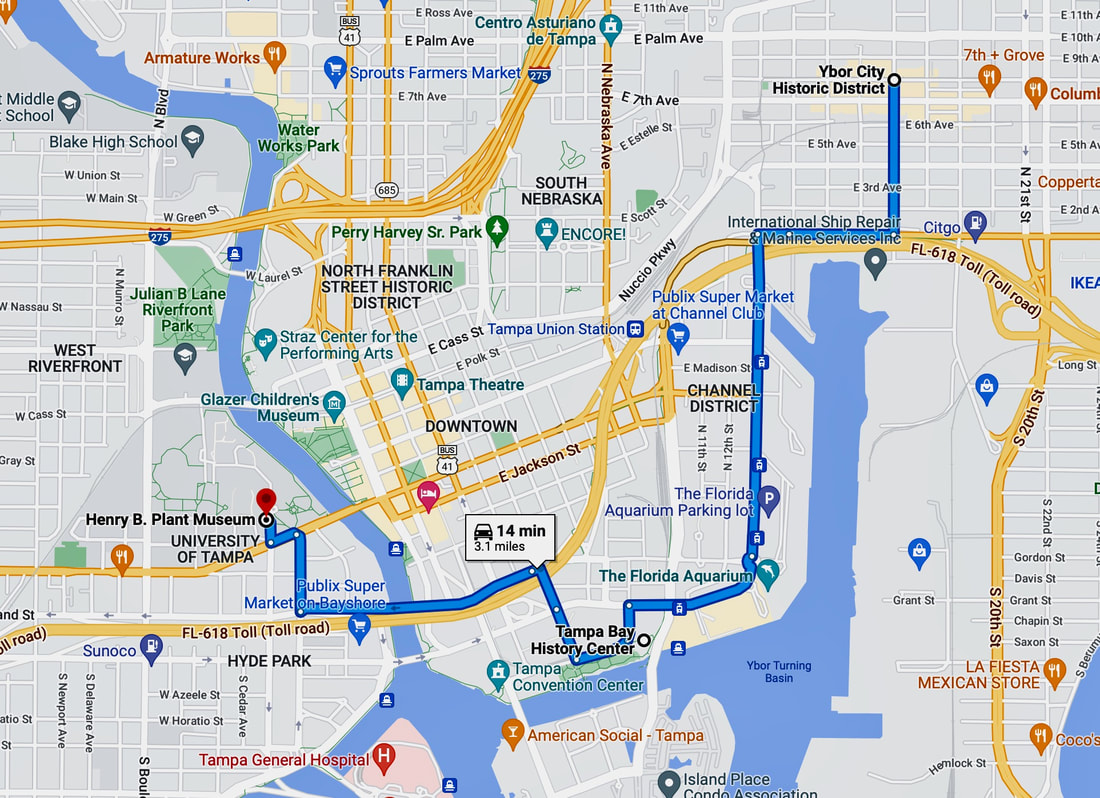

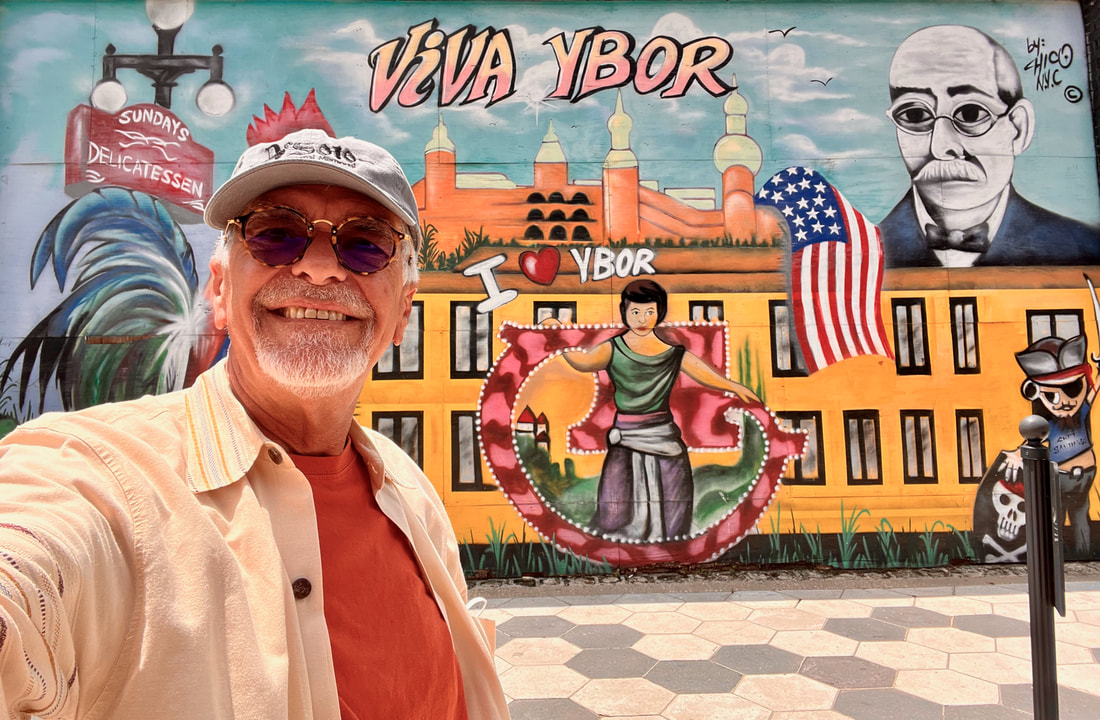

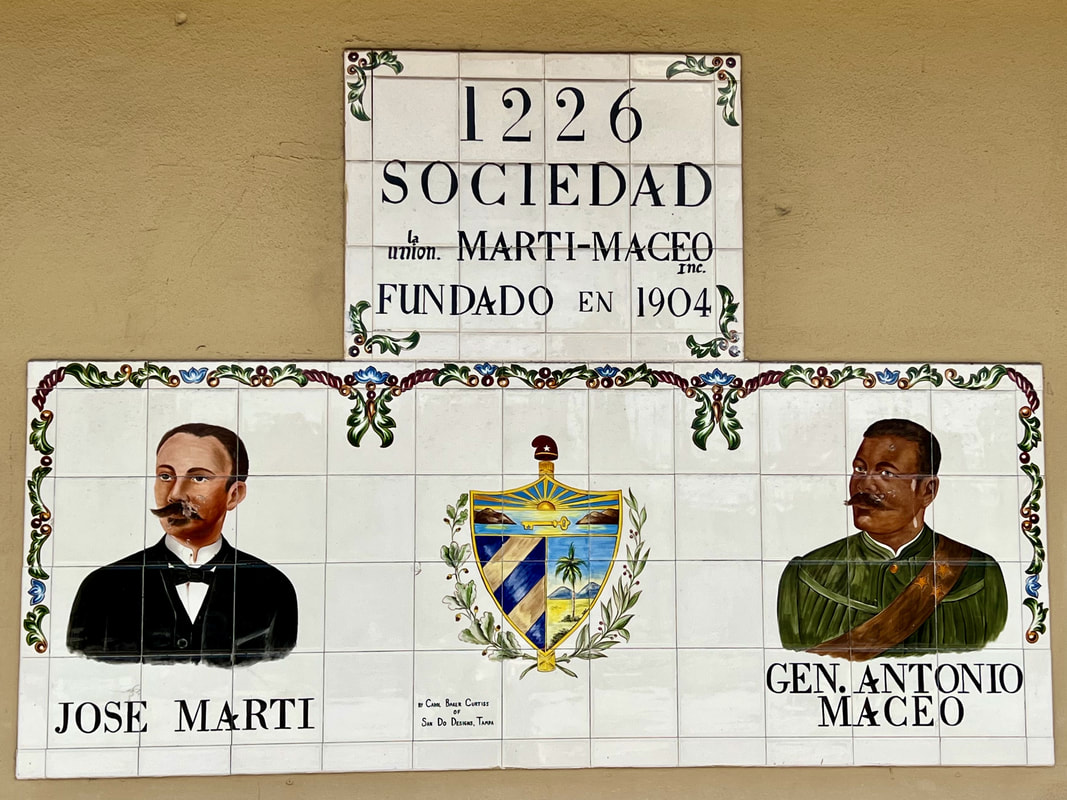

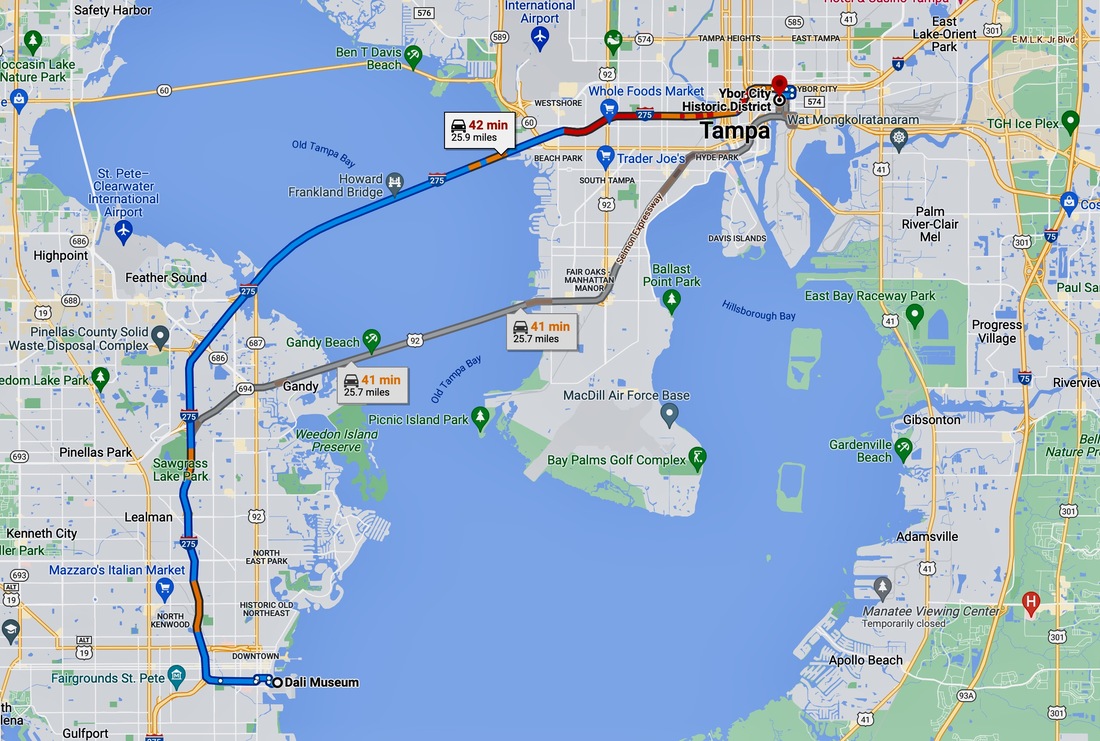

Although the war was fought for 10 weeks in 1898, American troops remained in Cuba until the island was granted its independence in 1902. Yet, as a result of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, the United States obtained possession of the former Spanish territories of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The Philippines were granted independence in 1946, but Puerto Rico and Guam have remained as unincorporated U.S. territories. And it was all launched from Tampa's Ybor City, by Cuban exiles who organized the Cuban Revolutionary Party led by José Martí, and from the Tampa Bay Hotel, by the U.S. Army led by Theodore Rosevelt. Both the hotel/museum and Ybor City are now designated as National Historic Landmarks. Back 1973, when I was a junior at the University of South Florida, I was also a reporter for The Tampa Times. And so I thought I knew this city, at least a little. But there is so much that has changed that I could hardly recognize it. Frankly, I might have been a little lost, had it not been for my friend Azucena Abed, who became my guide to Hispanic Tampa and took me to many more places than I expected to visit. It was great! Azucena: ´Mil gracias! To get to our next stop, we will follow the path of two 16th century Spanish expeditions, led by Panfilo de Narvaez and Hernando de Soto. We're going to Tallahassee! To enlarge these images, click on them! ——-->

|

32nd stop: Tampa Bay History Center

|

|

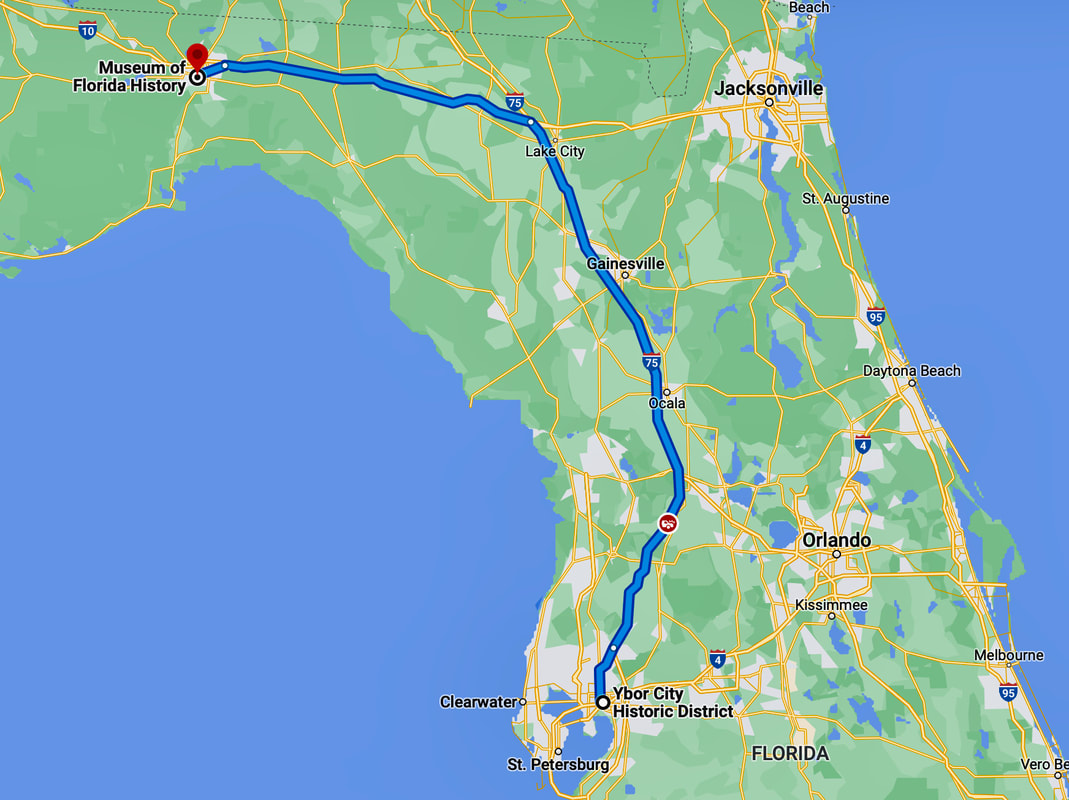

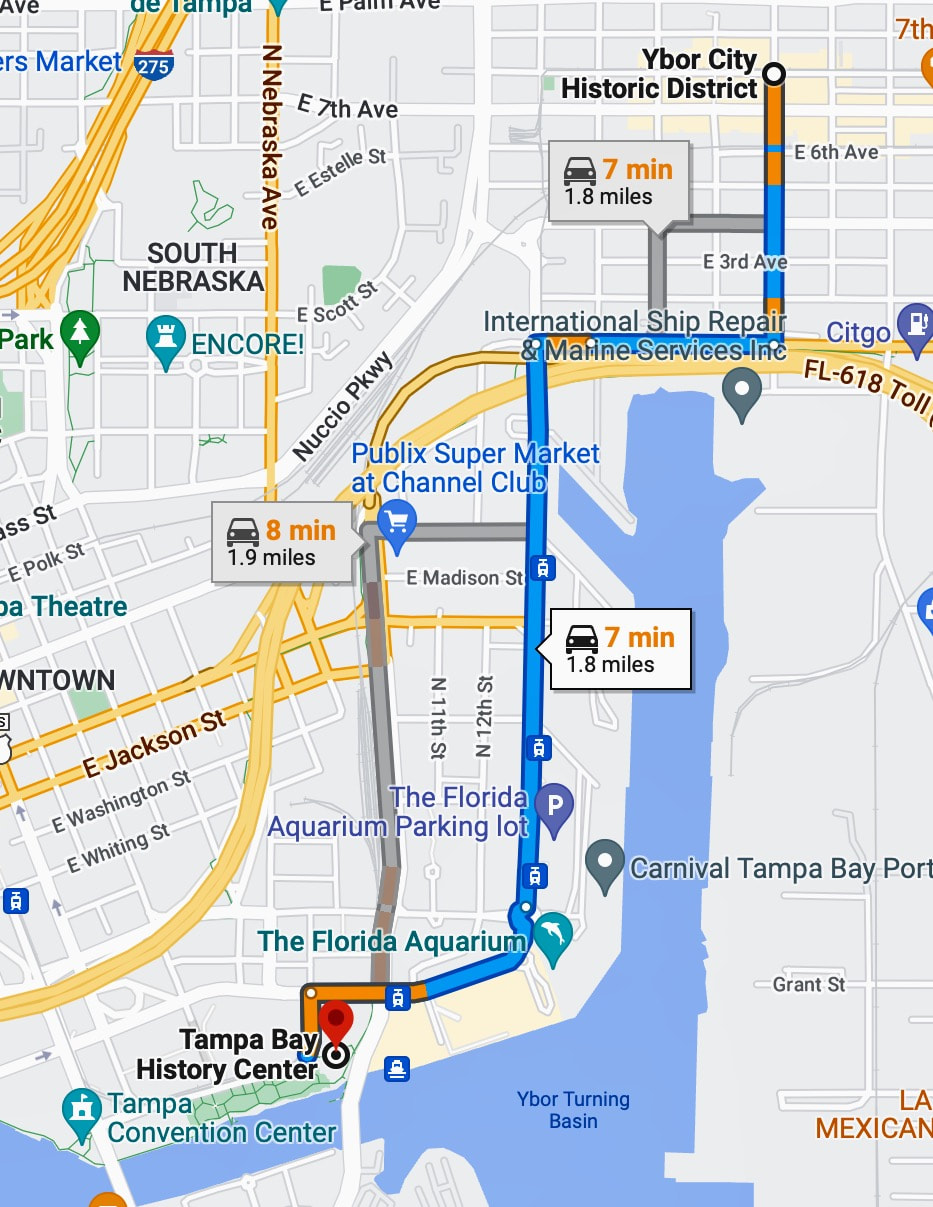

One exhibit here calls it "the Spanish-Cuban-American War," which is a much more accurate description. This is both where Cuban exiles led by Martí organized their revolution against Spain in the 1890s and where more than 15,000 U.S. Army soldiers led by Col. Teddy Roosevelt embarked for Cuba in the summer of 1898.

"With Cigar City's largely Cuban workforce, the issues of Cuba were those of Tampa," a History Center exhibit explains. Calling Tampa the "Cradle of Cuban Liberty," the exhibit notes that "During the 1890s, nearly every Cuban member of the Tampa workforce willingly pledged on day's salary per week toward Cuba's independence from Spain . . . From Tampa, Martí and other revolutionary leaders found a place to rally, recruit and train a growing force of insurrectos." |

|

Here you learn that Tampa's cigar industry "turned out millions of cigars annually and left long-term cultural impacts on the growing City of Tampa." While the first of Tampa's cigar factories opened in 1886, by 1920, there were as many as 300 working at full capacity, employing thousands of workers. And it was not until 1950s that Ybor City began transforming from an industrial center into a tourist attraction.

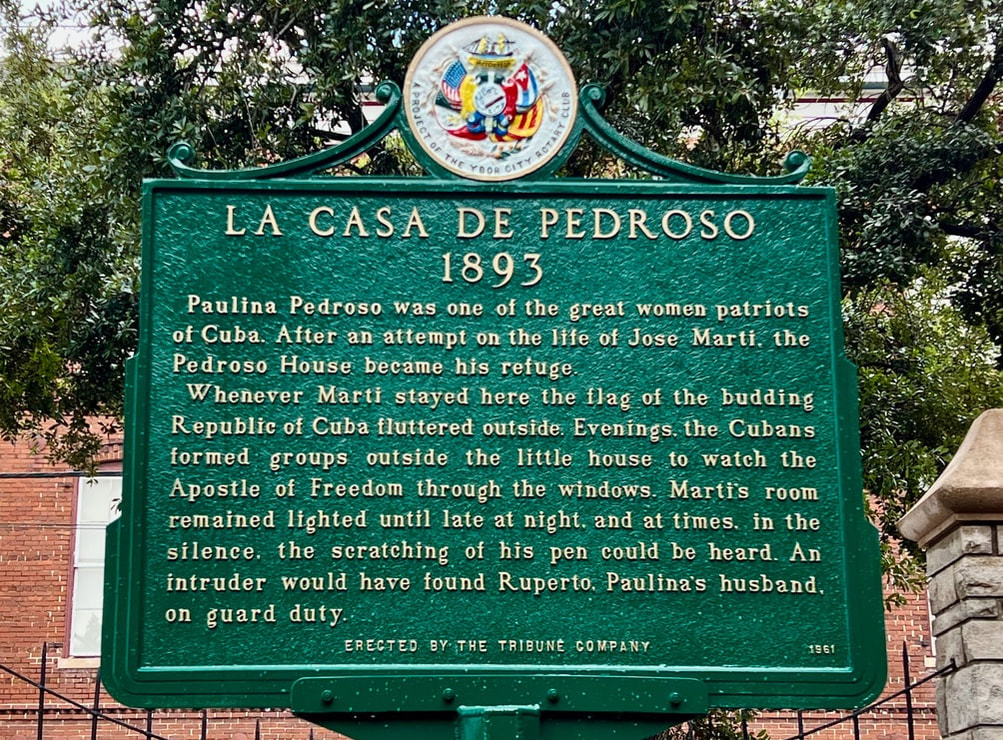

The amazing still-living history we saw in my last two stops in Ybor City is well-documented here. Even on the Tampa Riverwalk, just outside the History Center, there is a bust of Paulina Pedroso, introduced in my previous stop at Ybor City's Parque Amigos de José Martí. It was she and her husband Ruperto who ran the boardinghouse where Martí stayed when he was in Tampa. The plaque below her bust describes her as a "freedom fighter" who raised money to buy munitions for the Cuban rebels. "Ostensibly a humble cigar maker, her natural political skills made her a factor in winning Cuba's independence from Spain." |

|

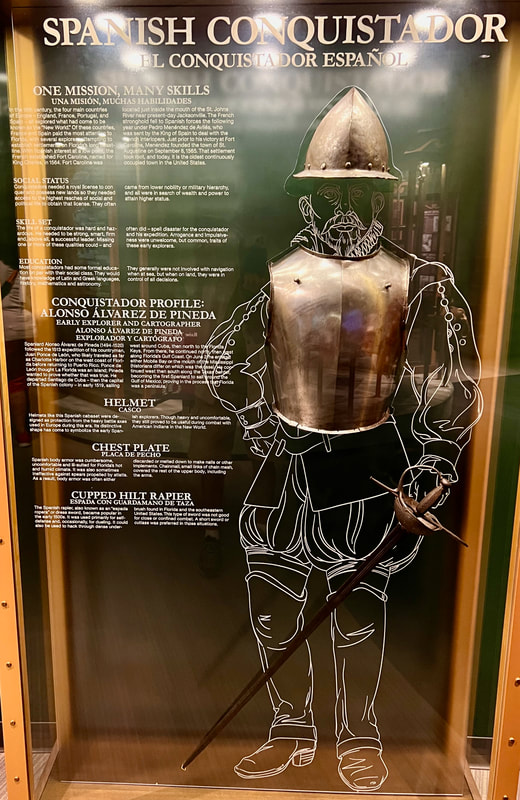

But of course, Florida's Hispanic history dates back much further than Ybor City, and that history is also well-represented here, from Juan Ponce de Leon's discovery of Florida in 1513, to Pedro Menendez de Aviles' establishment of St. Augustine in 1565, to the many famous conquistadors who first landed in the Tampa Bay area – Pánfilo de Narváez, Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Estevanico, Juan Ortiz, Hernando de Soto.

Here you learn that "the first cattle introduced to the American landscape arrived in Florida, from Spain, in the early 1500s — long before the legendary herds of the West and the famed American cowboy." Here you see the coins and other artifacts recovered from Spanish shipwrecks off the coast of Florida. |

|

There are extensive exhibits on the history of Cuba, Tampa and Florida, especially its native people. In fact, the presentation of how the Florida natives were treated by the U.S. government, after the Spanish had left, is hair-raising! It makes visitors see the huge difference in the way the Spanish and the Americans treated the Indians. In a nutshell: The Seminoles that the Americans couldn't kill were either driven into the Everglades swamps or forcibly moved to Indian reservations in Oklahoma! And yet nowadays, we have Black Legend-influenced people who blame the Spanish for the "genocide" of Florida natives. Not too many Americans are even aware of the three "Seminole Wars," because our history books avoid our shameful chapters. But this museum doesn't avoid it. Check out my photos from their exhibit on: The Seminole Wars.

|

|

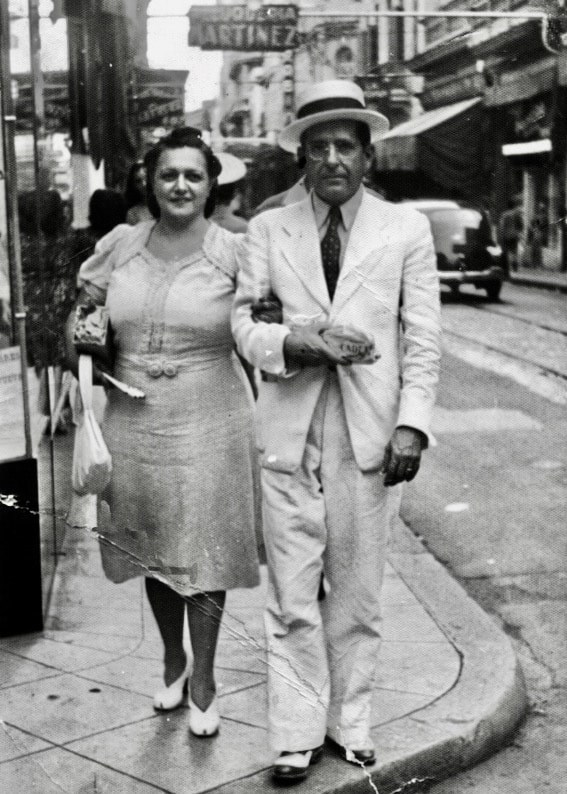

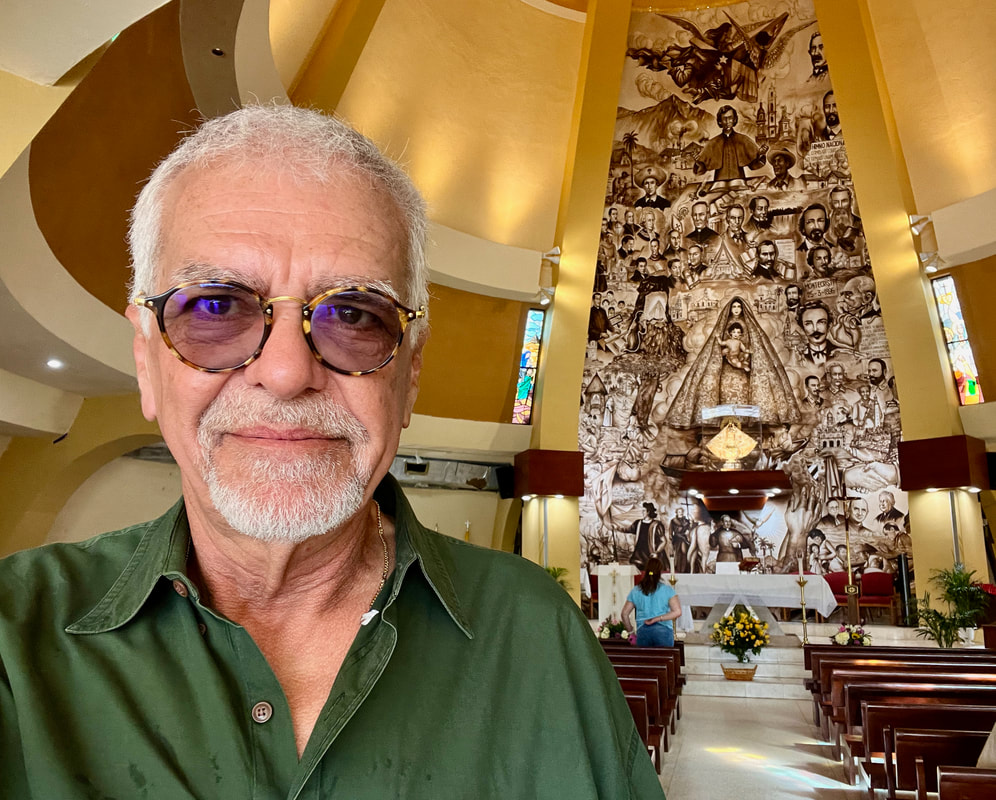

For me, this museum brought back emotional family memories. I saw how my grandfather met my grandmother! An exhibit recreating a cigar factory shows a lector reading to the workers and a woman rolling cigars. In the days before radio, factories hired "lectors" to entertain the workers by reading newspapers, magazine and novels. Since I was a kid, I've heard stories about how my grandfather Miguel, a lector, impressed and romanced my grandmother Ofelia when they both worked in a cigar factory in Cuba. It all came rushing back to me in this museum. Sometimes my search for our Hispanic roots gets very personal!

Next stop: Much more on Tampa's role in the Spanish-Cuban-American War, from another Tampa museum! |

31st stop:

|

|

Although Martí lived in Manhattan during his 15 years in exile, he came to Tampa frequently, because Ybor City's large Cuban exile community is where he found moral and financial support for his cause, not only from Cuban tobacco workers, but from Spanish tobacco factory owners.

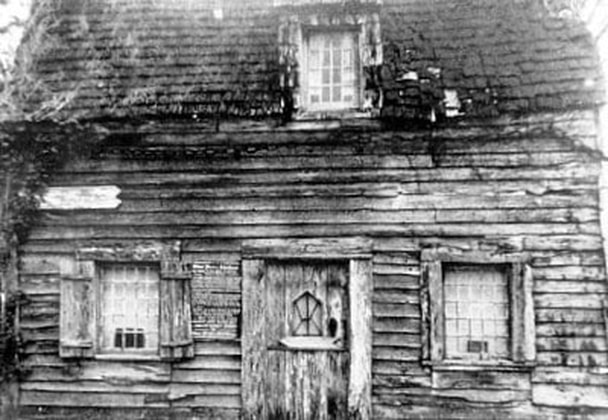

It was Martí's fiery speeches in Ybor City that earned him the title of “Apóstol de la Libertad de Cuba” (Apostle of Cuban Freedom). The boarding house belonged to Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso, the Afro-Cuban couple who nursed Martí back to health after he has poisoned by two Spanish agents in 1893. Cuban folklore says that many years later, before she died back in Cuba, Paulina requested to be buried with a photo of Martí. On the back, it was dedicated "to Paulina, my black mother." Needless t0 say, this place is bursting with history! The park has a statue of Martí, a bust of Cuban independence General Antonio Maceo, a modest mural-map of Cuba, and the Cuban and American flags. It is covered with soil from each of the original six Cuban provinces! At the nearby Tampa Riverwalk, where the city's most prominent citizens are recognized, there is a bust of Paulina Pedroso. The Pedroso house went through several transactions until it was purchased in the early 1950s by Cubans wishing to recognize its historic significance. When ownership was transferred to the Cuban government in 1956, at first there was talk of turning it into a museum. But when it was severely damaged by a fire, it was decided to turn it into a small park -- "Parque Amigos de José Martí -- dedicated to the memory of the patriot, poet, and journalist who led the island's revolution to win independence from Spain." However, the new Cuban Revolution delayed the park's opening until 1960. Tampa city officials agreed to maintain the park's lights and irrigation, but leave the landscaping and operation responsibility to the Cuban-American community in Tampa. So, other than the Cuban embassy in Washington, D.C., this is the only Cuban territory in the United States. And for Cuban exiles like me, who for many years have longed to step on free Cuban soil again, without having to deal with communists, this is it! It was great to be there! But frankly, it was not the same as the Cuba I knew. I think I will have to wait until the rest of Cuba is free. Next stop: Martí's story continues, at the nearby Tampa Bay History Center. |

3oth stop: Ybor City, Tampa

|

|

29th stop:

|

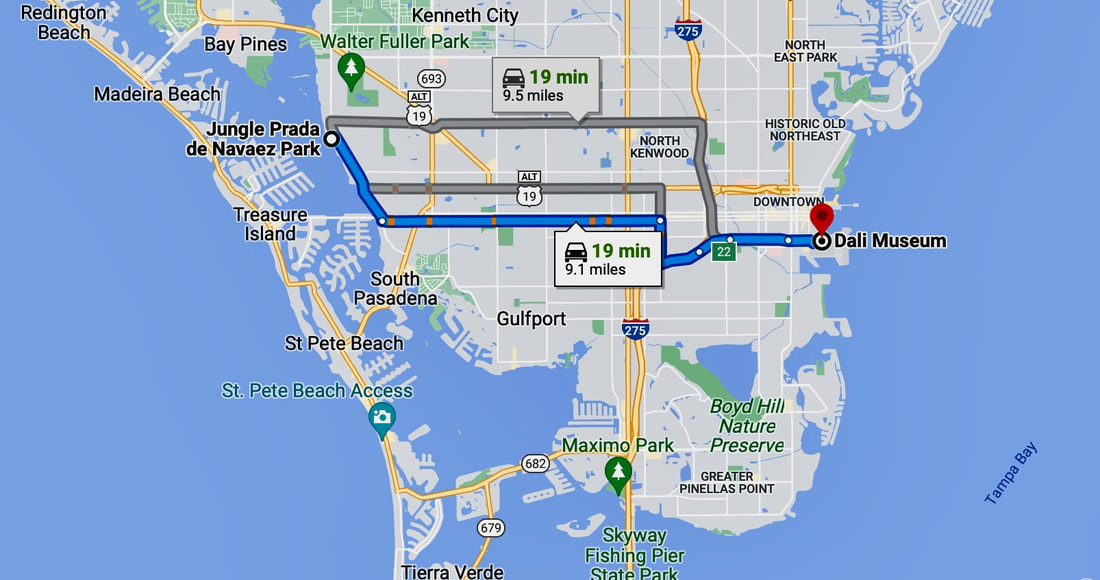

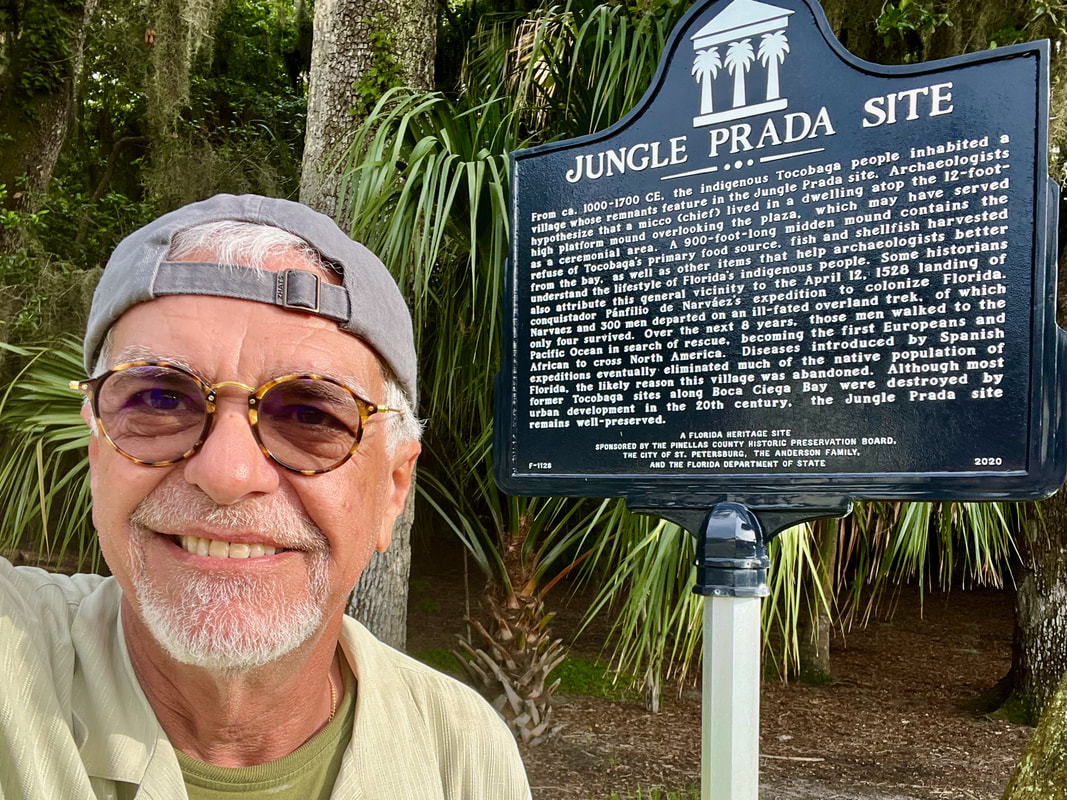

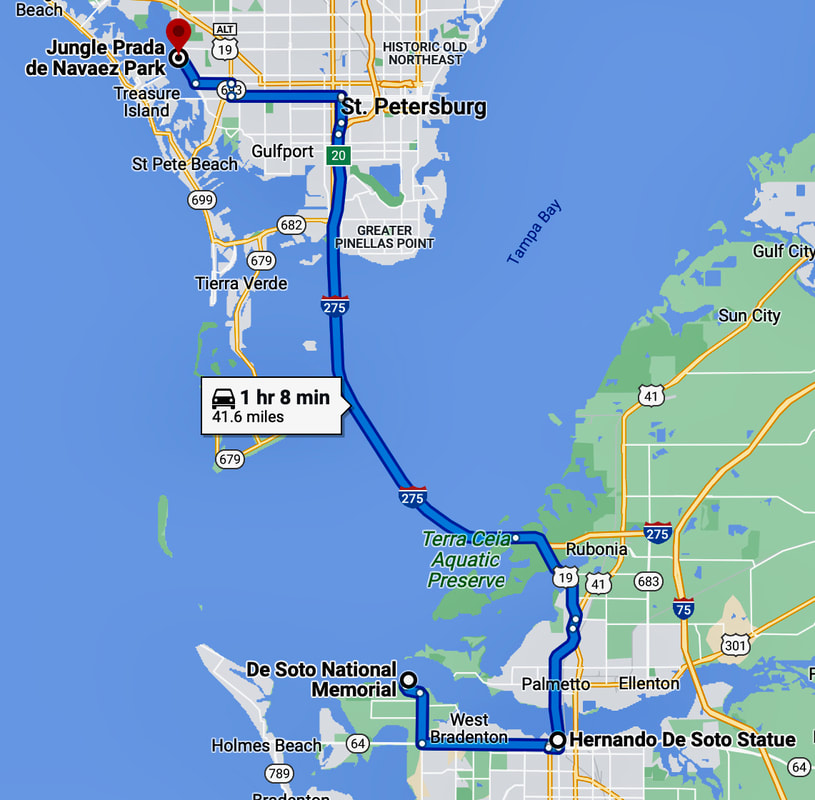

28th stop: St. Petersburg:

|

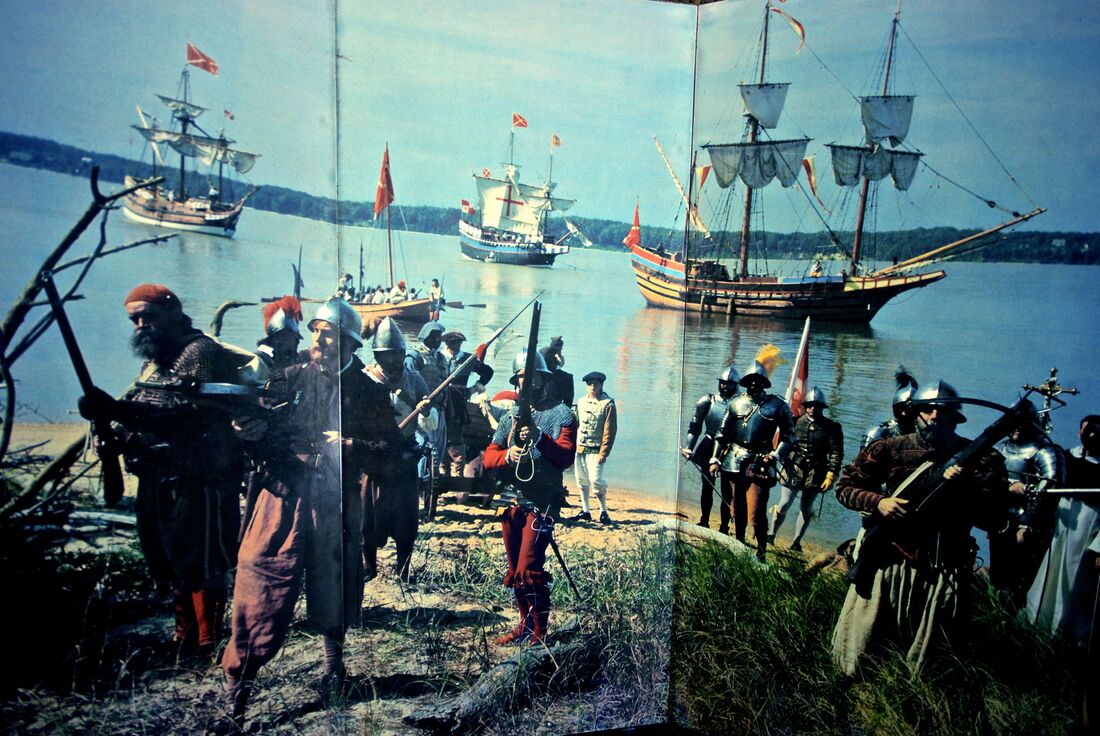

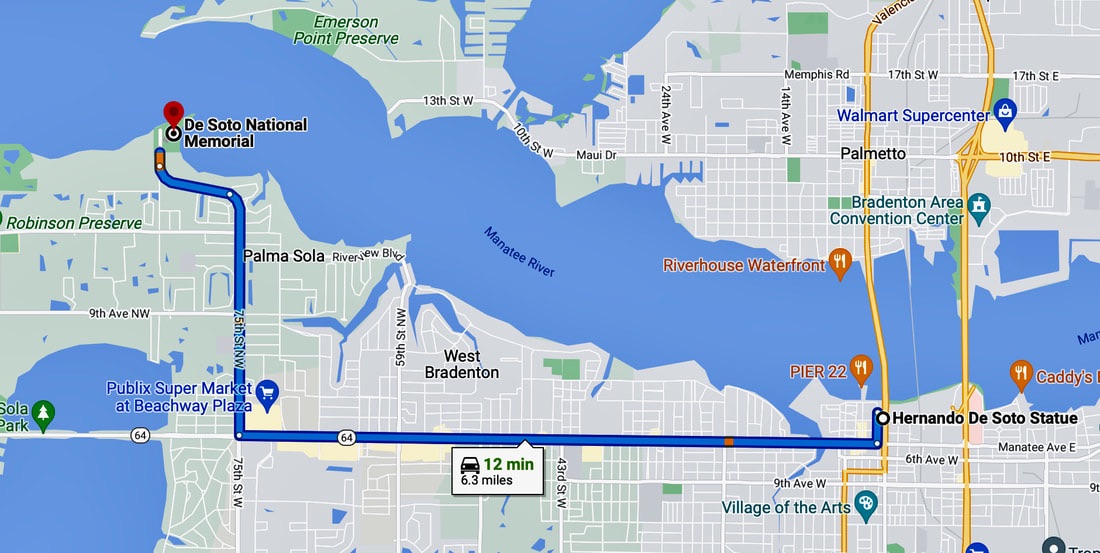

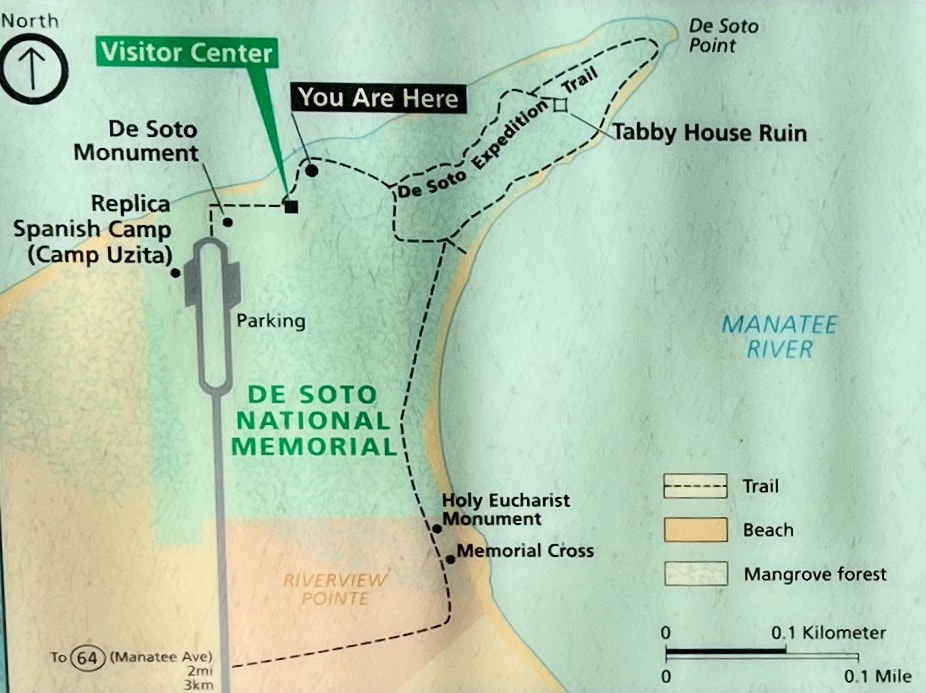

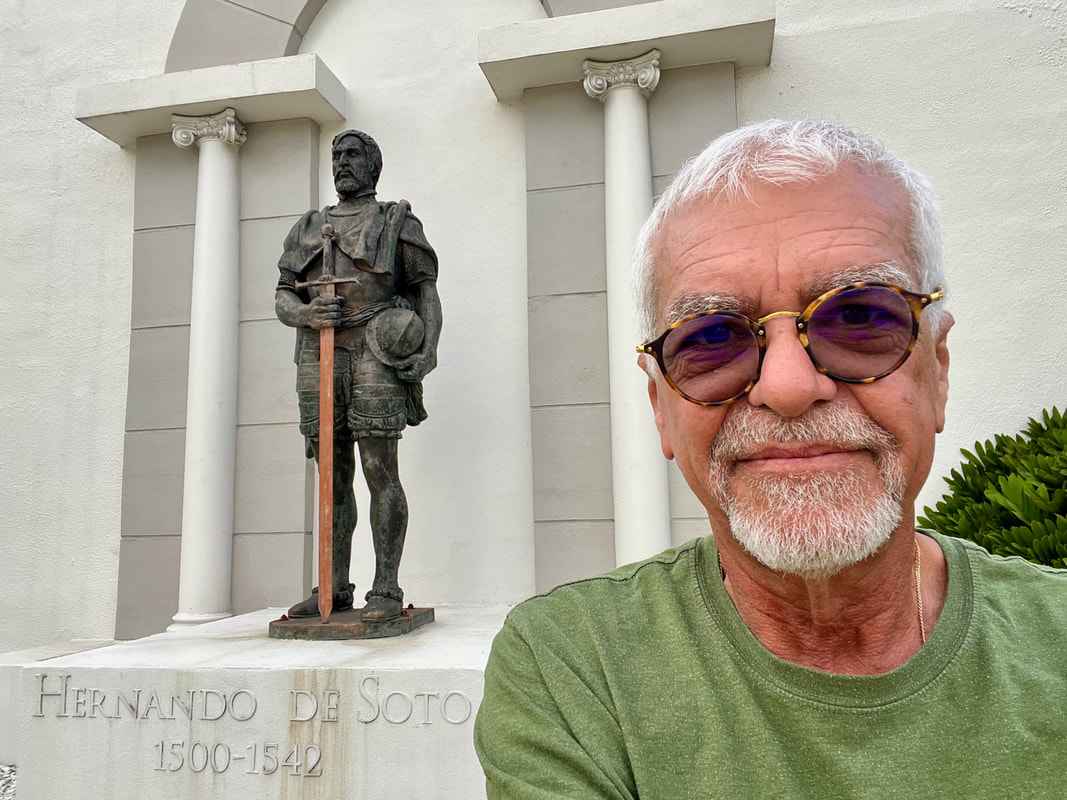

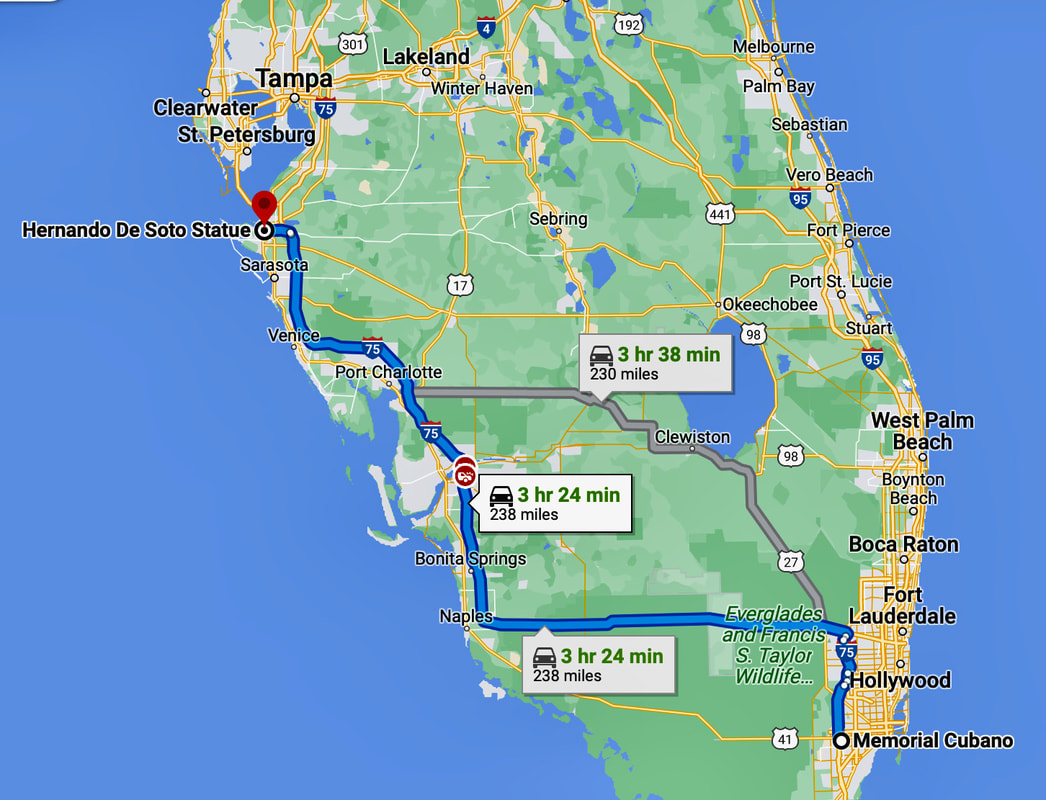

27th stop: De Soto National Memorial, Bradenton, Fl.At a point where the Manatee River converges with Tampa Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, where the 1539 Hernando de Soto expedition is believe to have landed, the De Soto National Memorial covers 26 acres of pristine mangrove jungle, with a three-quarter-mile trail that takes you though it - just like De Soto probably saw it almost five centuries ago.

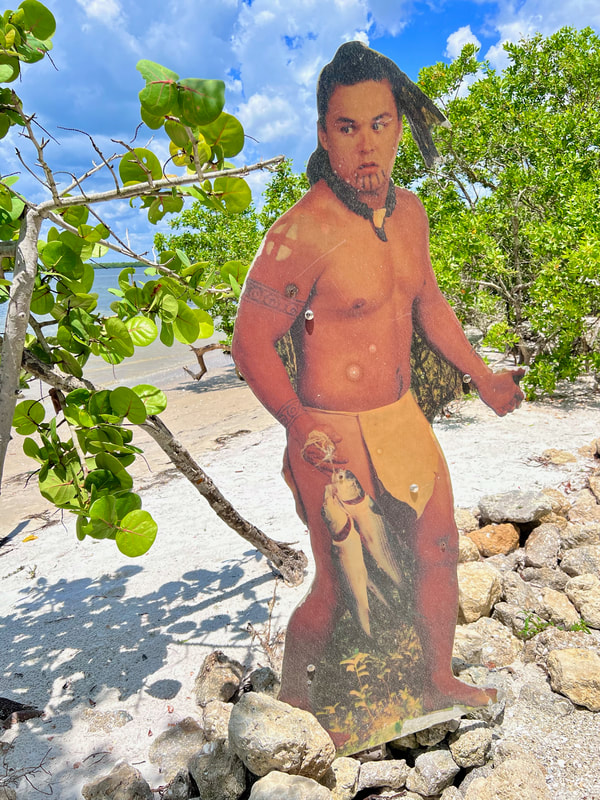

At the park's visitors center, you are met by fascinating exhibits, a video history lesson and opportunities (lol) to take selfies with a mask-wearing Spanish conquistador. What more can you ask for? But once you go out to explore the jungle on the "De Soto Expedition Trail," you find life size images of Native Americans and conquistadors scattered throughout the place. You are not just trekking through a tropical forest here; from the markers along the way, you are getting an education! Here you learn that, in 1538, Spanish King Charles V granted De Soto a royal contract to govern Cuba and “conquer, pacify and populate” La Florida - the land that Juan Ponce de Leon had discovered in 1513 and failed to conquer when he returned in 1521. And the land that another conquistador, Panfilo de Narvaez, had also failed to conquer 1528. You learn that De Soto was already a wealthy and renowned conquistador from having plundered the Inca empire in Peru, that he invested his fortune on the new expedition and came to Florida seeking similar fortune. You learn that he led a nine-ship flotilla with close to 700 men, a few women, 350 horses, a herd of pigs, several packs of bloodhounds and "equipment necessary to sustain an expedition of conquest." Since La Florida was then understood to be much bigger than the current State of Florida, De Soto understood his commission to cover limitless territory. And so you learn that "in their relentless pursuit of gold and riches," De Soto's army spent the next four years exploring "much of the interior of southern United States, from Florida to Texas." You learn that De Soto first established a base camp at the Indian village of Uzita, and within this park, you visit a small replica of the Uzita camp. You learn that this lush mangrove forest once covered much of the Tampa Bay coastline and presented an almost impenetrable obstacle for the De Soto expedition. As I explain in a Chapter 49, On the Trail of Conquistadors, because they were cutting through mangroves, while herding pigs, horses, war dogs and fighting natives who stood in their way, it took them three months just to reach the Florida panhandle - less than a five-hour drive nowadays! When they reached the Apalachee village of Anhaica, in what is now Tallahassee, Fl., they fought with the natives, settled for the winter, and celebrated the first Christmas in what is now the United States. See: America's First Christmas was Celebrated in Spanish. Their four-year, 4,000-mile hike finally lost its drive when De Soto died of fever and was buried in the Mississippi River in 1542. In this park you see that, contrary to popular belief, Florida natives were already a warring people when the Spanish arrived. You learn that before the Spanish raided Indian villages, the Indians were already raiding each other's villages. On the contrary, you also learn that De Soto had vowed to kill any Indian who would dare lie or betrayed him. Clearly, this park tries to be objective in its presentation of the Spanish conquistadors and those first encounters with native Americans. Without holding back, it shows that both were equally violent. Two more examples: “Emboldened by the conquest of the gold-rich Aztec and Inca civilizations in Central and South America several years earlier, the Spaniards came prepared for battle with armor, helmets, arquebus, crossbow, lance or pike in hand, some on horseback or with war dogs,” one marker explains. “Those people are so warlike and so quick,” another marker quotes a conquistador. “Before a crossbowman can fire a shot, an Indian can shoot three or four arrows, and very seldom does he miss what he shoots at.” This park asks you to deal with the reality of living in 16th-century Florida! For our next stop, let's visit the landing site of the 1528 De Narvaez expedition. It's only 35 miles north of here! |

26th stop:

|

Before we leave Miami,

|

Before we leave Miami,

|

25th stop:

|

24th stop: HistoryMiami Museum,

|

23rd stop:

|

22nd stop:

|

21st stop: Little Havana, USA

|

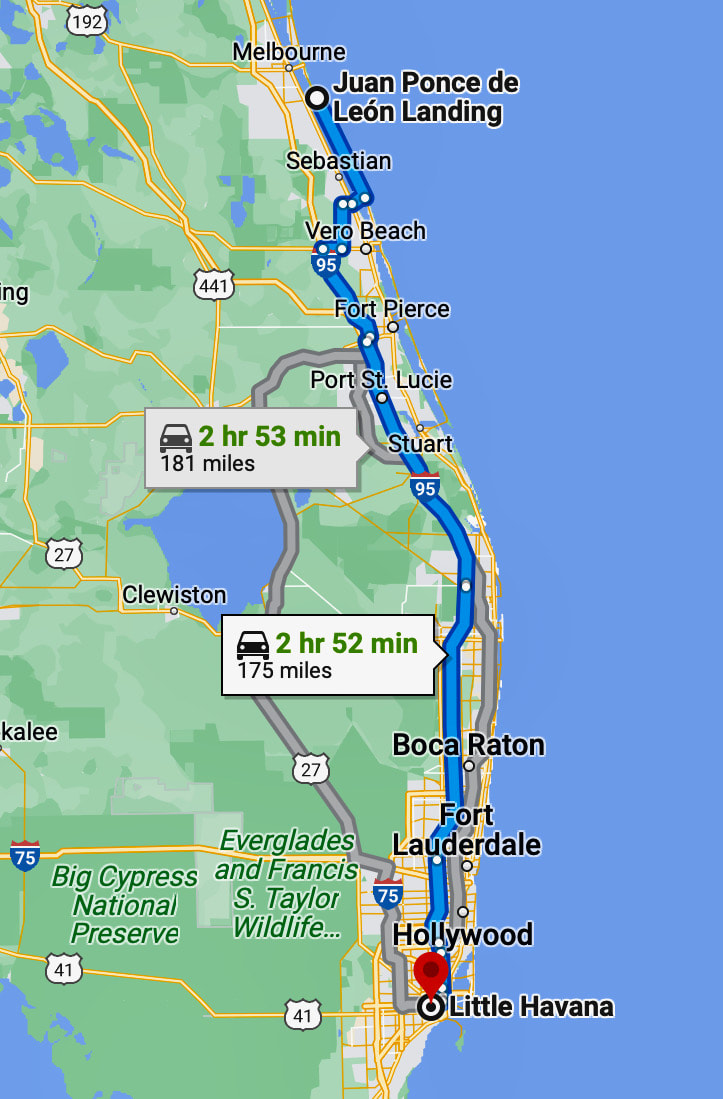

20th stop: Juan Ponce de Leon Landing,

|

19th stop: St. Augustine's statue

|

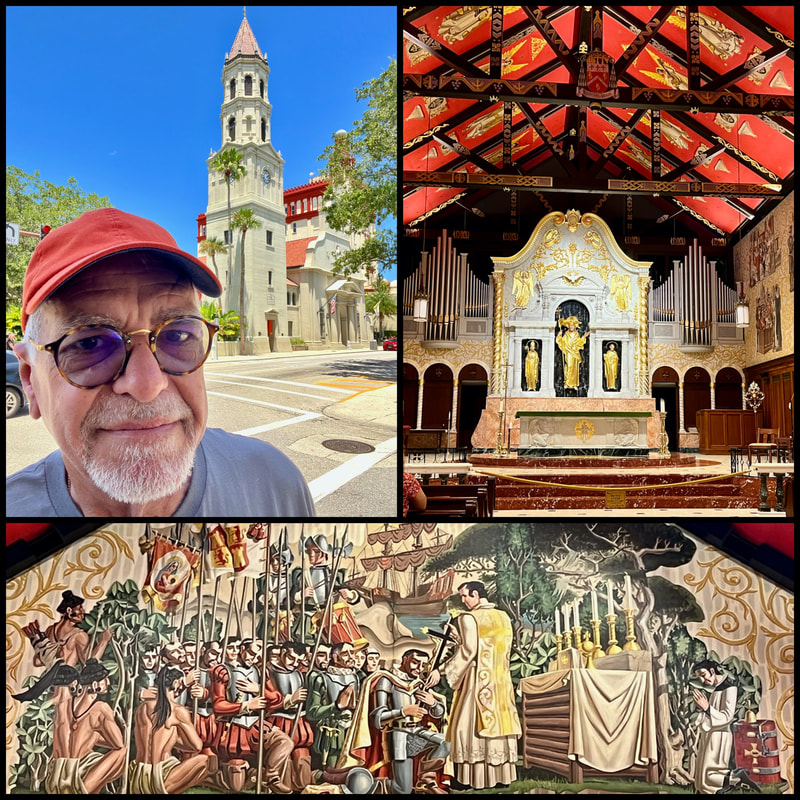

18th stop: St. Augustine's statue of its founderAs if still guarding the settlement he established in 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés stands in front of St. Augustine City Hall, a very impressive statue and equally majestic building.

In this mecca of Hispanic culture, where American tourists learn history just by going for a stroll, where they see all the history that was left out of their American History books, Menéndez de Avilés, is still a superstar. You can read more about him in "A Tale of Two Cities," my column on Jamestown and St. Augustine. But after revisiting both, that column is about to get a lot longer - a book chapter! For example, I took new notes from the plaque on the pedestal of this statue. "In memory of him," the plaque recognizes "the debt owed by the New World to Spain for the civilization, culture and progress contributed to Florida and to the Republic of the United States of America." Can we get more Americans to read that plaque, please? Of course, those same words also apply to the man who discovered Florida in 1513, Juan Ponce de Leon. He still stands a few blocks away, and we'll visit him next. |

17th stop:

|

16th stop: St. Augustine's 'Oldest Wooden School House in the USA'In the heart of the St. Augustine historic district, "The Oldest Wooden School House in the U.S.A." was closed when I arrived. But I have been there before, and it is a fascinating place.

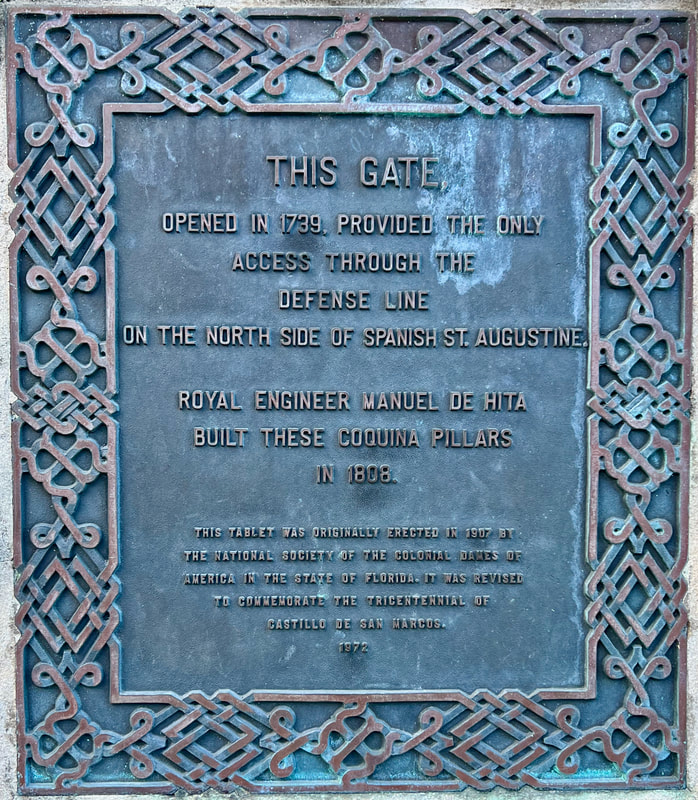

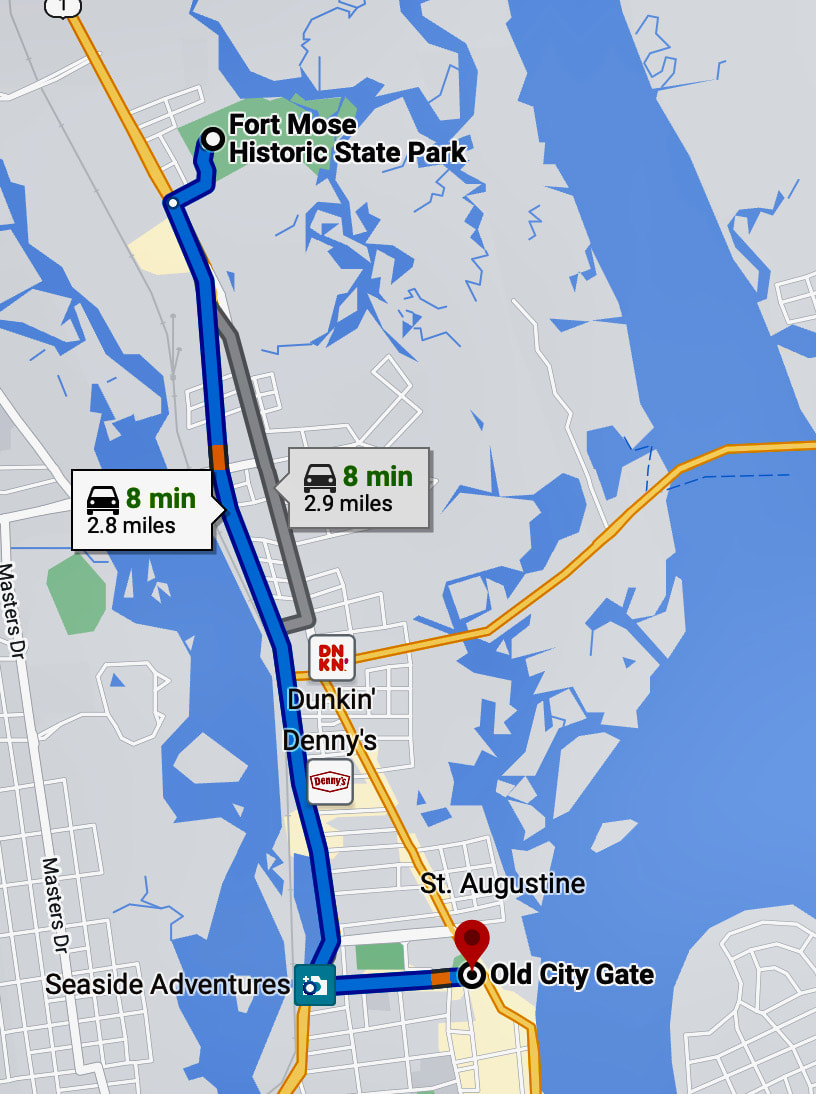

This was the home Juan Genopoly, who turned a portion of his house into a classroom for the children of the Minorcan community that had settled on the north end of George Street, just inside the city gate, in St. Augustine since 1777. Genopoly started his school when he bought the house in 1780, and since they were in British occupied Florida, the children were taught English too! Two of Genopoly's own four children went on to also teach there, and classes continued until 1864! But if this is the oldest school house, you ask, where is the oldest house? We are going there next! |

15th stop: St. Augustine's statue of Father Pedro Camps, spiritual leader

|

14th stop:

|

13th stop:

|

12th stop:

|

11th stop: St. Augustine,

|

10th stop: St. Augustine,

|

Ninth stop:

|

Eighth stop:

|

Seventh stop:

|

Sixth stop:

|

Fifth stop:

|

Fourth stop:

|

Third stop:

|

Second stop:

|

First stop:

|

To enlarge these images, click on them!

|

|

|