NYC Hispanic Landmarks

|

|

MONUMENTS

|

Simon Bolivar

|

BY ADELAIDA OSPINA-RODAS

The statue of Simon Bolivar, "El Libertador," stands at the main entrance of New York’s Central Park, on 59th Street and Sixth Avenue, together with two other statues, of Argentine General Jose de San Martin, and Cuban poet and activist Jose Marti. The corner is called Bolivar Plaza. One of South America’s greatest generals and the most outstanding figures of American emancipation against the Spanish Empire, Bolivar contributed decisively to the independence and sovereignty of today’s Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and he was the founder of Bolivia. He was recognized by his contemporaries for his great talents, his intelligence, his selflessness, his spirit of freedom that led him to give everything of his own to serve a noble cause of the independence of the South American countries from Spain, which today recognized him as their Founder Father. Born in Caracas, Venezuela on July 24, 1783, Bolivar was a military and politician of the pre-republican era of the Captaincy General of Venezuela. He died on December 17, 1830, in Santa Marta, Colombia. His mortal remains now lie in the National Pantheon in Caracas. His Central Park statue, created by sculptor is Sally Jan Farnham, was donated to the city by the Venezuelan government on April 19, 1921. In the statue, Bolivar, in full military uniform, rides his imposing horse, with its hoofs in the air. Its black granite pedestal features five coats of arms, representing the five countries he liberated. |

|

José de San Martin

|

BY ANNIE MALEMBE

This bronze statue of José De San Martín, depicting the Argentine general and South American liberator, stands at the main entrance of Central Park, on the Avenue of the Americas and 59thStreet, in Manhattan. His monument, in a plaza where the Avenue of the Americas meets Central Park, is one of three equestrian statues depicting Latin American emancipation patriots, including Venezuela’s Simon Bolivar and Cuba’s José Martí. Born in Yapeyú, Argentina on February 25, 1778, San Martín was a military leader, statesman, and national hero who fought and won independence from Spain in Argentina (1812), Chile (1818), and Peru (1821). His bold plan to attack the vice royalty of Lima, by crossing the Andes to Chile and going on to Peru by sea, led to the defeat of the Spanish empire in southern South America. After his victories, San Martín unexpectedly resigned the command of his army, withdrew from politics, and moved to France. He died in Boulogne-sur -Mer, France in 1850. San Martín’s Central Park statue is 14-feet tall statue stands on a 20.4-foot-tall black granite pedestal. Although it is larger than life-size, it is still smaller than its original, which is in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and was created by French sculptor Louis Joseph Daumas. It was donated to New York City by Buenos Aires in 1950, in exchange for a statue previously sent to Argentina of General George Washington, to whom San Martín is often compared. The original was erected in Buenos Aires on July 13, 1862. The New York replica was erected on May 25, 1951. |

|

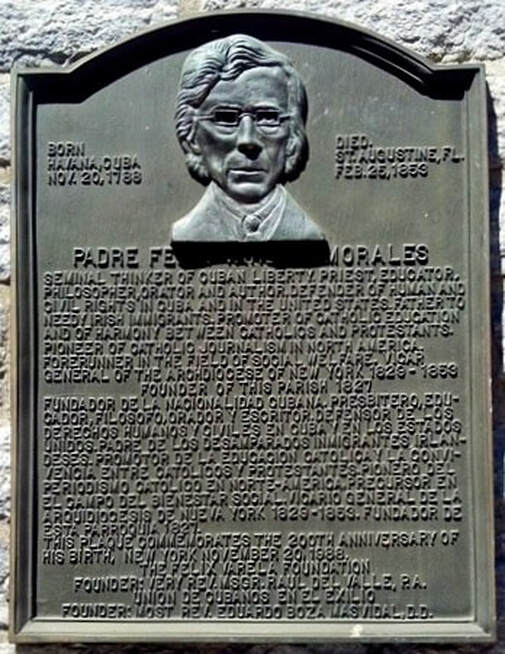

José Martí

|

BY DAHIANNA FELICIANO

The a bronze equestrian statue of Cuban writer and patriot José Martí, on Central Park South and Avenue of the Americas, depicts the moment when he was shot and killed in the battle of Dos Ríos, Santiago de Cuba, on May 19, 1895, at the start of the Cuban War of Independence, better known here as the Spanish-American War. This larger-than-life statue of the “Apostle of Cuban Independence” is one of three monuments dedicated to prominent Latin-American leaders in the "Bolivar Plaza" entrance to Central Park, where Martí rides besides Venezuela's Simon Bolivar and Argentina's José de San Martín. Born in Havana on Jan. 28, 1853, Martí was a writer, poet and philosopher who contributed to various journals throughout the Americas, and, while becoming an important figure for the Spanish American literary movement, inspired the revolution that liberated Cuba from Spain – and he did most of it from New York City! His writings in defense of liberty were inspirational to many, not only in Cuba, but throughout the Americas. But he was imprisoned by Spanish authorities in 1868 and eventually forced into exile in 1880 – t0 New York City, where he lived the last and most productive 15 years of his life. From his Greenwich village apartment, with a lot more freedom to write, Martí organized the Cuban Revolutionary Party (1892) and became the mastermind of the revolution that eventually freed the island. Unfortunately, Martí did not live long enough to see a free Cuba. Feeling the need to lead by example, although not a military man, Martí returned to fight for Cuba's freedom and was promptly shot and killed by Spanish troops at Dos Ríos, Santiago de Cuba on May 19, 1895. His 18.6 feet tall Central Park monument, created and donated by American sculptor Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington, illustrates a staggering yet determined Martí after being fatally wounded while atop his horse during the 1895 battle. Vaughn Hyatt Huntington bestowed the statue as a gift to the Cuban government for presentation to the people of New York City in 1959. The Cuban government then donated the monument’s dark granite 16.5 feet pedestal, but it was not erected in Central Park until 1965, with the words “Apostle of Cuban Independence, Leader of The Peoples of America and Defender of Human Dignity. His Literacy Genius Vied With His Political Foresight." |

|

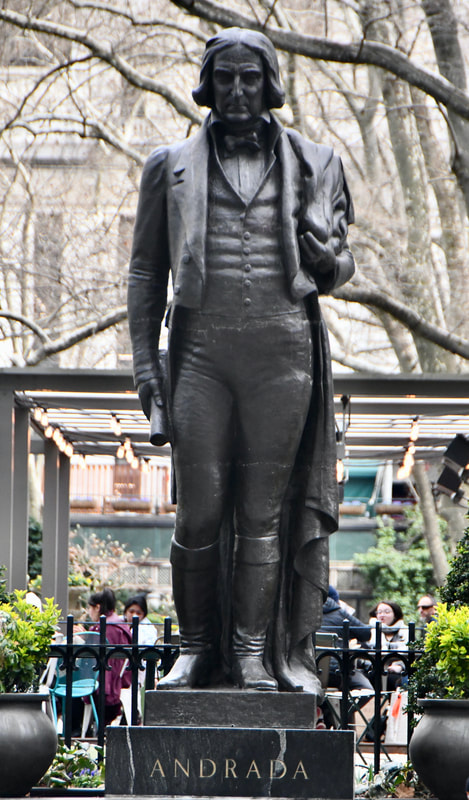

Juan Pablo Duarte

|

BY JOHANY MEREJO

The larger-than-life bronze statue of Dominican patriot Juan Pablo Duarte stands at the corner where the Avenue of the Americas meets Canal Street in Manhattan. Dressed in stately, 19th-century garb, the bearded father of Dominican independence from Haiti is resting his left hand on a cane and holding a scroll with his right. Born on January 26, 1813, Duarte was a writer, poet, philosopher, revolutionary, visionary, and liberal thinker who fought to free the eastern half of the island of Hispaniola from Haitian rule. In 1838, he was one of the founders of La Trinitaria, a political organization which began the resistance against Haitian occupation, and he led the movement until the Dominican Republic won its independence from Haiti on February 27, 1844. Yet, after helping to establish the new Dominican Republic, Duarte's differences with conservatives in the new government forced him into exile. He was a very well-educated, honorable man. He was a teacher, fluent in several languages, and his wisdom and skills helped him make a living in Caracas, Venezuela, where he died on July 15, 1876, at age 63. He rests in the "Altar de la Patria" mausoleum at Puerta del Conde in the Dominican Republic. His New York statue, which is 10.6 feet tall and stands on an 8-foot-tall granite pedestal, was created by Italian artist Nicola Arrighini, donated by the Dominican Government to the City of New York, and dedicated on January 26, 1978. |

|

Benito Juarez

|

BY DIONALY CARRASCO

This statue of Benito Juarez, one of Mexico's greatest political leaders, stands at Bryant Park, on the Avenue of the Americas between 41st and 42nd streets, in Manhattan. Juarez became Mexico’s first indigenous president after the victory of the reformers during Mexican civil war (1858-1861) and served from 1861 to 1863. He served as president again from 1867 to 1872, during the time when the reformers helped preserve Mexico’s independence from the French Invasion. “Among individuals, as among nations, respect for the rights of others is peace," Juarez said. Juarez came from humble origins. He was a Zapotec Indian, born in Gualatao, Oaxaca in 1806. Yet he studied law and became governor of Oaxaca and a major reform figure, a force in Mexico's becoming a democratic society. He died in Mexico City in 1872. The Bryant Park 5’5 statue, created by sculptor Moises Cabrera Orozco, was donated to New York City by the State of Oaxaca on behalf the Mexican Government. |

|

Admiral David Farragut

|

BY GAIL DIAZ

The bronze statue of Union Navy Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, also known as the Admiral Farragut Monument, stands at the north end of Madison Square Park, on 25th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues in Manhattan. Farragut is best known for his Civil War victory at the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay and his legendary battle cry “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” as he led his fleet through a field of submerged explosives, “torpedoes.” The Union created three new naval ranks just for him. He was the first ever rear admiral, vice admiral and full admiral in the U.S. Navy. After the Civil War, Farragut’s picture was used in Navy recruitment posters and U.S postage stamps. Born in 1801, his father was Jorge Farragut, a Spanish-American immigrant and a veteran of the Revolutionary War -- making him a second generation war hero. He was adopted at the age of 7 by Captain David Porter, a naval officer and friend of his biological father. His naval career began when he was nine years old. He served under Porter as a midshipman. At the age of 11, he fought in the War of 1812 and when he turned 12 he was promoted to the rank of prize master. By 1855 he had risen to the rank of captain. On July 25, 1866 he was promoted to full admiral. The statue depicts Farragut in full naval uniform, with a sword at his side and holding binoculars, standing on his ship, ready to command his fleet. Standing on a 9 foot tall black granite pedestal, the 9-foot tall bronze statue was a collaboration between sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and architect Stanford White. It was cast in 1880, dedicated on May 25, 1881 and donated by the New York Farragut Association. |

|

El Cid

|

BY SIRKY SANCHEZ

This statue of Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid Campeador, the Castilian champion and medieval hero who won numerous battles against Moorish invaders of Spain in the 11th Century, stands at Audubon Terrace, a courtyard on Broadway between 155th and 156th Streets, in Manhattan. El Cid was born in north Burgos, the capital of Castile, around 1043 AD and became a nobleman and military leader in the court of Emperor Alfonso VI of León and Castile. He fought against the Moors in the early Reconquista in medieval Spain. He died in July, 1099 AD. His bronze 1927 statue, by renowned sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington, stands on a limestone base in front of the Hispanic Society of America (museum) building in Washington Heights. It depicts the legendary Spanish hero riding his horse and lifting his flag and lance, as if celebrating a victory. There are replicas of this statue in San Diego, San Francisco, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Seville and Valencia, Spain. But we have the original in New York City. |

Spanish War Memorial |

BY MAIRA CARDENAS

The Spanish War Memorial, dedicated to the American soldiers from the Bronx who lost their lives during the Spanish American War, is a 31-foot tall column topped by a globe, at Graham Triangle, on the corner of 137th Street, Third Avenue, and Lincoln Avenue in the Bronx. The column's pedestal has a plaque cast from the metal recovered from the U.S.S Maine, the American battleship that mysteriously exploded and sank in Havana Harbor and ignited U.S. involvement in the Cuba's War of Independence from Spain, better known here as the Spanish-American War. While in Cuba to protect American interests on the revolution-torn island, the Maine was sabotaged on February 15, 1898. The explosion killed 268 crew members. Since they failed to identify the cause of the explosion, the United states blamed Spain and declared war on April 25, 1898. Less than four months later, the United States had defeated Spain and the Spanish American War came to an end with the Treaty of Paris, which allowed Cuba to gain its independence and forced Spain to give up Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States. Erected in 1919, The Spanish War Memorial has stood on Graham Triangle for more than a century. The engraving on its pedestal notes that it is dedicated, "To the brave men of Bronx Borough who gave their lives for their country in the war with Spain." |

|

David Farragut Gravesite

|

BY FLOR JOHNSON

Obelisk marking the gravesite of Civil War hero Admiral David Glasgow Farragut at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. He is best known for leading the Union Navy to victory, as he shouted, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead," in the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864. The son of a Spanish immigrant, Farragut was a sailor who went on to become this country's first the rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral. All three ranks were created just to promote him! During the Civil War, Farragut was the commanding officer who led his Union Navy to victory, especially at Mobile Bay, where -- while already taking Confederate cannon fire from the shoreline -- he ordered his sailors to ignore the floating mines that were then known as "torpedoes." He became such a hero that, after the Civil War, Farragut’s photos were used on U.S. postal stamps and Navy recruitment posters. He was born in Tennessee, on July 05, 1801, the son of Jorge Farragut, an immigrant from Minorca, Spain and Elizabeth Shine, a Scot-English American. He and his father were both descendants of conquistador Don Pedro Farragut, who served the King of Aragon in the 13th century. His father was a captain and calvary officer in the Tennessee military. When his mother died of yellow fever in 1808, his father, and his father need help raising him, he was adopted by his father’s best friend, Navy officer David Porter, who raised him to become a sailor. Farragut took after his adopted father to the ocean and got his title as navy cadet at 9 years old. Two years later, he was already involved in battle during the War of 1812. However, although he is remembered as one of the greatest war heroes of American history, most of today’s U.S. Hispanics don’t know he was one of them! Farragut’s impressive gravesite is a tall, marble column on a stone pedestal. At the base of the column, cut into the stone, are emblems of Farragut's military history, including his Civil War Flagship; the Hartford; an anchor, a sword and a compass. It is on Woodlawn’s Aurora Hill – lot number 1429-44, Section 14 – south of the intersection of Webster Avenue and East 233rd street in the Bronx. The monument advanced the new Woodlawn graveyard when it was established in 1863, becoming a landmark that set the early standard for the burial ground’s monuments. It was created by New York City-based stone carvers, Casoni and Isola, who collaborated with Sculptor Giovanni Benzoni. It is now a National Historic Landmark. |

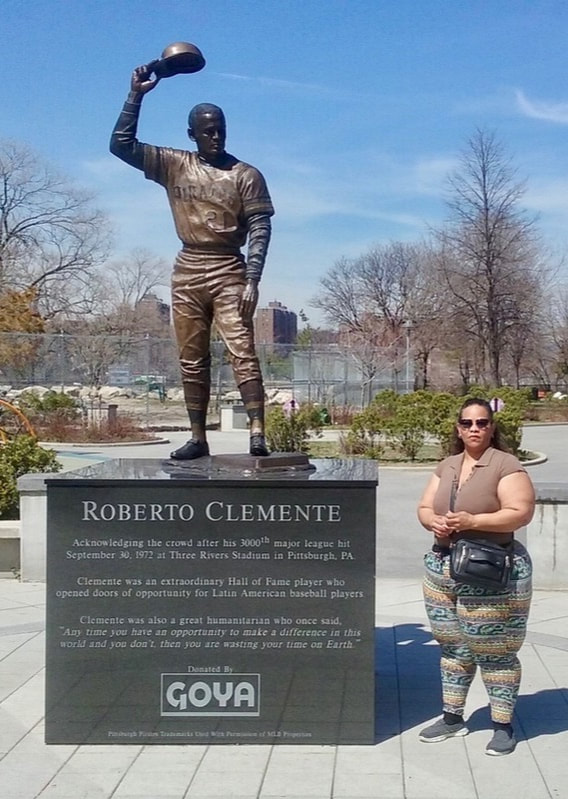

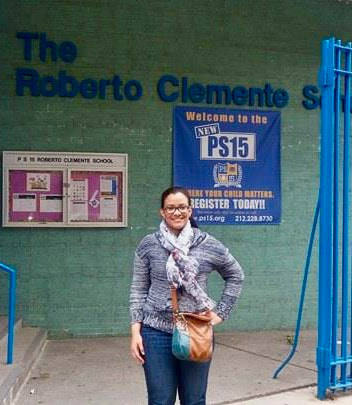

Roberto Clemente |

BY MELISSA TRINIDAD

The Statue of Roberto Clemente, depicting the Puerto Rican baseball superstar saluting his fans after hitting his 3,000 hit in 1972, is at Roberto Clemente State Park, at West 179th Street and West Tremont Avenue, in the Bronx. But reaching that amazing mark, at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, PA., on Sept. 3, 1972, doesn't say enough about Clemente's amazing career. He was an All Star for 12 seasons, the most valuable player in 1966 and the batting leader in 1961, 1964, 1965 and 1967. He was a Gold Glove winner 12 consecutive seasons from 1961 to 1972. His batting average was over 300 in 13 seasons. He was the first Puerto Rican player to help win a World Series as a starter, in 1960. He also received a World Series MVP Award in 1971. Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker was born on August 18,1934 in Barrio San Anton, Carolina, Puerto Rico, to Don Melchor Clemente and Doña Luisa Walker, and became the pride of the Puerto Rican community. He started his professional baseball career in 1952, at the age of 18, with the Cangrejeros de Santurce, a winter league team and franchise of the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. From Santurce he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was assigned to play their top affiliate the Montreal Royals. In 1954 Clemente was the first pick of the draft for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He joined the Pirates in 1955. He was married in 1964. He and his wife had three boys. Sadly, Clemente was killed in a plane crash in the Atlantic Ocean on Dec. 31, 1972, after taking off from Isla Verde, Puerto Rico to take aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. In 1973, with baseball waiving a five-year retirement requrement, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, being a superstar and dying on a humanitarian mission, Clemente's image transcended baseball. In 1974, the one-year-old "Harlem River Park" -- alongside the Harlem River -- was renamed "Roberto Clemente State Park." The statue, created by sculptor Maritza Rodriguez and donated by Goya Foods, was erected on in the park's recreational playground on July 5, 2013. |

|

The Immigrants

|

BY JUSTIN ACOSTA

The bronze sculpture dubbed “The Immigrants,” facing the New York Harbor that received so many people from all over the world, is an impressive sight in lower Manhattan’s Battery Park. This sculpture, just south of the park’s Castle Clinton, is a reflection and homage to the diversity of those who have traveled to America. Across the bay, when the Statue of Liberty says (in her inscription) "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” these are the people she is talking about. They are all in this statue! Here you see people who obviously went through life-changing journeys seeking a better life in America, including an Eastern European Jew, a freed African slave, a worker and a priest. They represent people of all races, ethnicities, and religions --extending their arms, as if giving thanks for their arrival. They represent all immigrants, from those who escaped an oppressive regime, to those who wanted to reunite their separated families, to those seeking opportunities and a better way of life. The 10 feet tall and 8 feet wide statue was dedicated on May 4, 1983 and rededicated on August 1, 2005. Created by sculptor Luis Sanguino, the statue was donated by Samuel Rudin to pay tribute to the memory of his immigrant parents. |

|

PFC Emilio Barbosa

|

BY LAEDI LOPEZ

This small bronze and granite plaque, in Manhattan’s Bennett Park, recognizes the heroism of Private First Class Emilio Barbosa, a Nicaraguan immigrant who grew up in Washington Heights and was killed in battle aboard the USS Nevada BB-36 when that ship was struck by a Japanese kamikaze airplane on March 27, 1945. Barbosa (1926-1945) enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II, at the at of 17. A veteran of D-Day in Europe, Barbosa was manning his 20 mm turret when his ship was struck in Okinawa, le Shima, Japan. The kamikaze struck the ship’s main deck, causing a massive explosion that killed 10 other Marines. Yet even after it was attacked, the USS Nevada continued to supply naval gun support for the ground troops. Barbosa was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star with combat “V” (for Valor) for his heroic service during the attack. Bennet Park is at West 183rd Street and Fort Washington Avenue in upper Manhattan. Erected on August 30, 1996, the Emilio Barbosa Memorial plaque recognizes his "valor and duty to country, along with the other Marines who sacrificed their lives so that we may live in freedom." |

|

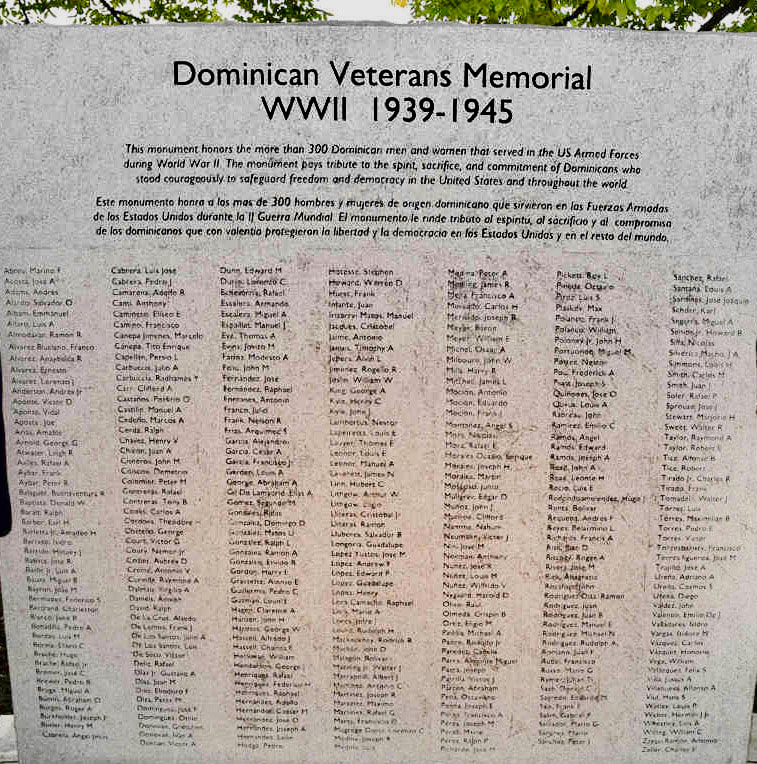

Flight 587 Memorial Wall

|

BY CLARA CHAVIRA

The commemorative granite wall in the Rockaway Park section of Queens, pays tribute to the 265 people who died in the crash of American Airlines Flight 587, traveling from Queens, New York to Santo Domingo, on November 12, 2001. The “Flight 587 Memorial Wall,” at the south end of Beach 116th Street on the Rockaway peninsula, has the names of the victims, including many Dominican-Americans, inscribed on its surface. Flight 587 crashed shortly after take-off from JFK airport. It was the second largest aviation tragedy in U.S history. The monument, designed by Dominican artist Freddy Rodriguez, quotes Dominican poet laureate Pedro Mir, in Spanish and English: "Después no quiero más que paz" – "Afterwards I want nothing more than peace." The memorial provides a quiet place of contemplation amid Rockaway’s busy and heavily trafficked commercial center. Oriented towards the ocean beyond, an arching granite wall sits atop an elevated plinth surrounded by planters and nine pear trees. Voids in the wall frame allow views of the water and sky and provide places to leave flowers and mementos to loved ones. A single threshold cuts the wall at its center, and at exactly 9:16 a.m. every year, on the anniversary of the crash, sunlight passes through that threshold and aligns with the pattern of paving on the ground. |

STREETS

|

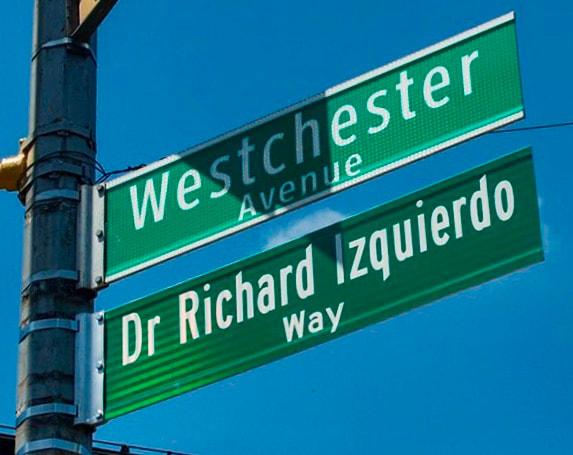

Celia Cruz Way

|

BY RAMON RUIZ

Celia Cruz, the Latin music superstar who had so much influence on Hispanic culture throughout the world, is now honored and remembered on Celia Cruz Way, the street named after her in 2021, at the corner of Reservoir Avenue and 195th street in the Kingsbridge Heights section of the Bronx. Known as “The Queen of Salsa,” Cruz was one of the most influential figures in Latin music and culture. Her music brought joy and dance movements to the United States and gave Hispanic people recognition and pride. In the Bronx, you could hear her music, and feel her influence, at every bodega and family gathering. Born in Cuba on October 21, 1925, Cruz started her career in Havana the 1960’s and then moved to the United States, where she began to shine as a superstar. As soon as Cruz made New York her home, she was beloved and was seen as the epitome of Hispanic culture. Her devotion to New York City was profound, so it was a no brainer that the street was named after her. Celia Cruz Way leads to the Woodlawn Cemetery, where she is buried. Her influence has lived on even after her death in 2003 at the age of 77. Now she is memorialized on Celia Cruz Way, which is by the Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music. Having a street named after a person is not an easy task. There is a process that requires a petition that must be presented to the city. Approval for Celia Cruz Way was won by Cruz’ executor, Omer Pardillo Cid, and City Councilman Fernando Cabrera, who represents District 14 in the Bronx. They showed dedication and devotion to “The Queen” to achieve this goal. But of course, it was Celia Cruz they were recognizing. She was the superstar who made New York the capital of Salsa music – the one who is still beloved in the Bronx! |

|

Juan Rodriguez Way

|

BY MIGUEL PÉREZ

In the Washington Heights and Inwood sections on the upper West Side of Manhattan, Broadway is also called Juan Rodriguez Way, in recognition of the first immigrant in Manhattan, a native of the what is now the Dominican Republic. Rodriguez arrived in 1613. This is 12 years before Dutch colonists establish New Amsterdam, and 51 years before the English take control of the colony and rename it New York. Born in Santo Domingo of a Portuguese sailor and an African woman, Rodriguez arrives on a Portuguese ship and decides to stay. He marries a Native American woman and establishes a family. He builds a very lucrative business, trading furs for European tools with the natives and the explorers who came to the New World. But he is not only the first immigrant. Rodriguez is also the first person of both European and African heritage to live in Manhattan. And he is not only the first Latino, he is the first New York Dominican! In 2012, New York City recognized him by co-naming a portion of Broadway, "Juan Rodriguez Way." In two predominantly Dominican neighborhoods, from 159th Street in Washington Heights to 218th Street in Inwood, many people now can look up an see streets signs recognizing that one of their ancestors arrived here first! |

|

Mariano Rivera Ave.

|

BY JONELL PAYAMPS

The former River Avenue, outside Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, was renamed (Mariano) Rivera Avenue in 2014, in honor of the legendary Panamanian relief pitcher who played for the New York Yankees for 17 seasons and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2019. Born on November 29 of 1969, Rivera was active in Major League Baseball (MLB) for 19 seasons, including 17 of those seasons when he played a huge role as the Yankees’ closer. He started his MLB career in 1995 and retired in 2013. He won five championships and made 13 All-Star game appearances. He also holds the record for the most saves ever in the MLB at 652. Rivera had a career earned runs average of 2.21 and 1,173 strikeouts, meaning he would give batters an extremely hard time when they would come up to the plate. He was popular for his 95-mph cut fastball and nasty cutter that was nearly impossible for hitters to touch. When hitters did make contact with his cutter, it would potentially break their bats. Once the Yankees would make a call to the bullpen to signal in for Rivera to come out in relief, competitors pretty much knew the game was over. When Rivera was into the Baseball Hall of Fame on July 21, 2019, he became the first-ever player voted into the hall by a unanimous vote. Affectionally known as “Mo” by his teammates, not only was he recognized for his talent on the field, but for his character, a truly amazing and caring person off the field. On May 5, 2014, the street outside Yankee stadium was renamed. Rivera’s legacy was recognized by New York City Councilwoman Maria Del Carman Arroyo. who represents District 17 and led the movement to designate “Rivera Avenue.” |

INSTITUTIONS

|

El Museo del Barrio

|

BY MADLY DE LA ROSA

El Museo del Barrio, the only Hispanic institution on Fifth Avenue’s “Museum Mile,” has been the premier showcase for Latin American and Caribbean art in New York City, especially the work of Puerto Rican and Nuyorican artists, for more than 50 years. El Museo, at 1230 Fifth Avenue, between 104 and 105 Streets, presents rotating temporary exhibits of Puerto Rican and Latino modern art, and draws from its own permanent collection of more than 8,000 objects covering more than 800 years of Latin American, Caribbean and Latino art, -- from pre-Columbian Taino artifacts and traditional arts, such as Puerto Rican Santos de Palo, to 20th century drawings, prints, paintings, sculptures, photography, documentary films, and video. Many of these permanent collection items are also exhibited online. They also host all sort of special events, from educational programs to renowned festivals, especially its annual Three Kings Day Parage. The museum has a performance space, a children’s theater, and a café. And it is all meant to preserve the art and culture of Puerto Ricans and all Latin Americans in the United States. It began back in the days of the Nuyorican and Civil Rights movements, in reaction to the city’s mainstream museums, which were largely ignoring Hispanic art and culture. It was founded in 1969 by Puerto Rican artist and educator Raphael Montañez Ortíz and a group of parents and community activists who wanted their children to have a place to learn about Hispanic culture. And it began in a public-school classroom. The museum then moved to several East Harlem storefront locations between 1969 and 1977, when it moved to its current location, on the first floor of the new-classical Heckscher Building, which it shares with a school and several organizations. It was originally dedicated to Puerto Rican art and culture, and it has gradually grown to include all Latinos. This museum makes me feel proud to be Latina. |

|

Repertorio Español

|

BY JUNGMIN PARK

Repertorio Español, the longest running Spanish-language theater in New York, and the city’s top showcase for Spanish and Latin American playwrights and actors, presents some of the best Hispanic theater productions in the United States. Founded by three friends and great collaborators, producer Gilberto Zaldivar and director Rene Buch, and musical director Pablo Zinger, Repertorio has been promoting the rich heritage of the Hispanic theatre since it moved to Gramercy Arts Theatre, at 138 East 27th Street in Manhattan, in 1972. The highly acclaimed company has presented more than 250 plays. More than 1.5 million patrons, and 750,000 high school students have seen Repertorio’s productions, including anything from contemporary plays to Spanish classics. Since its inception, the company has received wide acclaim from newspaper critics and audiences. Since 1991, the theater also offers simultaneous translation, giving non-Spanish speaking audiences an opportunity to enjoy the work of Hispanic American playwrights, and introducing them to many talented performers. Repertorio received the 2011 OBIE Award for Lifetime Achievement, a 1996 Drama Desk Special Award for presenting quality theater; a 1996 Obie Award for the play series Voces Nuevas (New Voices); the New York State Governor's Award; and numerous citations from the Asociación de Cronistas de Espectáculos (ACE) and the Hispanic Organization of Latin Actors (HOLA). More recently, Repertorio presented the world premiere in Spanish of Nilo Cruz's Ana en el trópico (Anna in the Tropics) – which won Pulitzer Prize! To its credit, the company considers education as its fundamental mission, and it is represented through its educational program, called ¡Dignidad! – which means both dignity and self-esteem. With this program, many students and teachers have been able to enjoy and learn from the theatre since 1971. |

Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music

|

BY JULY TORRES

Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music, named after the Cuban Salsa superstar who conquered the hearts Latin music lovers all over the world, is dedicated to New York City youth who wish to pursue a musical path. Located at 2780 Reservoir Avenue, next door to Carman Hall in Lehman College, this this high school opened in 2003, the same year when Cruz died and was buried the Bronx’s Woodlawn Cemetery. When former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg got word that there was a new school of music opening in 2003, he insisted that the school be named after Cruz. Although it was originally named “Bronx High School of Music,” Bloomberg held a conference at Lehman College, where he announced the school’s name change to “Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music,” on August 21, 2003. Cruz’s impact on the music world along with her childhood dream of becoming a teacher was a factor in honoring her trajectory by naming a school after her. Born in Havana in 1925, Cruz grew up planning to become a literature teacher, but that soon came to a halt when she found a passion for music and decided to pursue it. After she fled Cuba in the early 1960’s, became a U.S. citizen, and voiced her opposition to the Fidel Castro Communist regime, she was banned from returning to her homeland. So, based in New York, she rose to fame in the 1960s, when she turned to Salsa music, and became that genre’s ultimate superstar. She died in 2003 at the age of 77. |

|

Casita Maria

|

BY ANTHONY VALERIO

Casita Maria Center of Arts & Education is a New York City public school for grades 6-12 in the Hunts Point area of the South Bronx. It all began i1934, during the Great Depression. That’s when Casita Maria was organized by two sisters, Claire and Elizabeth Sullivan. They started in a small apartment in East Harlem, with the goal of helping recently arrived Latino families with the education support needed to achieve the American Dream. In 1961, Casita Maria was relocated to the South Bronx. As the Bronx burned in 1970, Casita Maria continued to expand, providing services for the homeless, drug addicts, teen pregnancy and thousands of children. In October 2009, the NYC Department of Education partnered with Casita Maria to open a beautiful six-story educational and cultural facility that would better serve the children in the Hispanic community. Today, Casita Maria has about 1,500 students in a range of arts, education and public programs, including after-school and summer programs. In 2014, 100% of students who attended the after-school program graduated from high school. |

|

Instituto Cervantes

|

BY MAIRA CARDENAS

Instituto Cervantes, is a non-profit organization founded by the Spanish government in 1991 with the goal of promoting the Spanish language and culture all over the world. Its New York office, at 211 East 49th Street, in Manhattan, is one 75 centers in multiple countries in five continents, with headquarters in Madrid. It pursues advancement of the Spanish language among New Yorkers. This Institute was named after Miguel de Cervantes, perhaps the most important writer in the history of Spanish Literature. His novel, Don Quixote, is considered the most influential work of literature from the Spanish Golden Age. Because Spanish is often called “la lengua de Cervantes,” it is fitting that an organization created to promote the Spanish language bears his name. |

|

Boricua College

|

BY LURIE ANN GONZALEZ

Boricua College is an educational institution established in 1974 to meet the educational needs of the Puerto Rican and Hispanic community in New York City. Starting with 26 students, the college became the first four-year bilingual institution of higher education in the United States. Boricua College currently has some 1,200 students enrolled in eight different curriculums leading to associate degree and bachelor’s degrees. Its courses are open for everyone, regardless of race, color, religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, or veteran status. It also offers individualized learning programs that follow a student's pace towards achieving their career goals. The name "Boricua" is used to describe a person born in Puerto Rico, or of Puerto Rican ancestry. It comes from the Taino word "Borikén,” to describe Puerto Rico. It means "Land of the brave and noble lords." The current campus, completed in 2010, is a 14-story building at 890 Washington Avenue, in the Bronx. |

|

El Taller Latino Americano

|

BY CLARA CHAVIRA

El Taller Latino Americano (The Latin American Workshop) is a community-based nonprofit arts and education institution that has been bridging the gap between North and South Americans – through the language of art, dance, and music – since 1979. Founded by Argentine musician and songwriter Bernardo Palombo, El Taller began in Lower Manhattan, relocated to the upper Upper West Side, and then again in 2014 to its current location at 215 E. 99th Street, on the Upper East Side. It offers programs in the arts, English and Spanish language courses, an art gallery, and a “music laboratory” that has drawn performances by many American and Latin American “new wave” superstars. By partnering with public schools, the MTA, hospitals and other community organizations, El Taller serves as a workshop for New Yorkers to gather and engage with culturally diverse groups that speak different languages. Gathering on this common ground of creativity, well over 500 people meet at El Taller every month, to share ideas, participate in classes and to find creative inspiration as well as a refuge in the middle of New York City. For more than three decades, numerous New York institutions – from the New York Public Library to Montefiore Hospital – have entrusted El Taller’s innovative, conversation-focused classes to teach Spanish to their employees. This is a place where artists, students and community members get to share their cultural heritage. |

|

Hostos Community College

|

BY KAREN ANDERSON

Hostos Community College, on the Grand Concourse in the South Bronx, was named after Eugenio Maria de Hostos, a renowned Puerto Rican writer, educator and patriot who was part of the movement to liberate Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain in the late 19th century. He was disappointed when Cuba got its independence, but his native Puerto Rico became a U.S. colony after the Spanish-American War. Born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, on January 11, 1839, Hostos became known as "The Great Citizen of the Americas," because he travelled and lived in several counties - including almost a year in New York - promoting the struggle for freedom and independence for the Americas. He died in died in 1903 in Santo Domingo, where he is buried. The college began in 1968 because Puerto Rican and other Hispanic community leaders saw the need for a community college in the South Bronx. By 1970, the school started with 623 students in a former tire factory. After four years, when enrollment had increased to 2,000 and the college was in dire need of more space, the state legislature passed a bill giving the college access to 500 Grand Concourse. In the same year, the college was granted full accreditation by the Middle States Association. Today, Hostos Community College is part of CUNY, the nation’s leading urban public university serving more than 500,000 students at 25 colleges. In six buildings and with more than 7,000 students Hostos offers 28 associate degree programs and two certificate programs that facilitate easy transfer to CUNY four-year colleges or baccalaureate studies at other institutions. As it was from its biginning, most of the college’s students are Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and others from Central America and other Caribbean islands. |

PLAYGROUNDS

Which New York City Hispanic-named streets, monuments, schools and other landmarks are we missing? Let us know at: [email protected]