42. Marking America's Birthplace

|

By Miguel Pérez

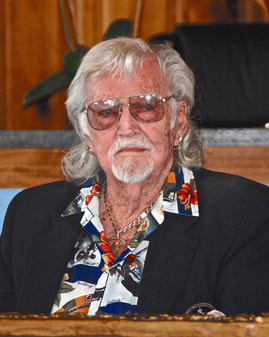

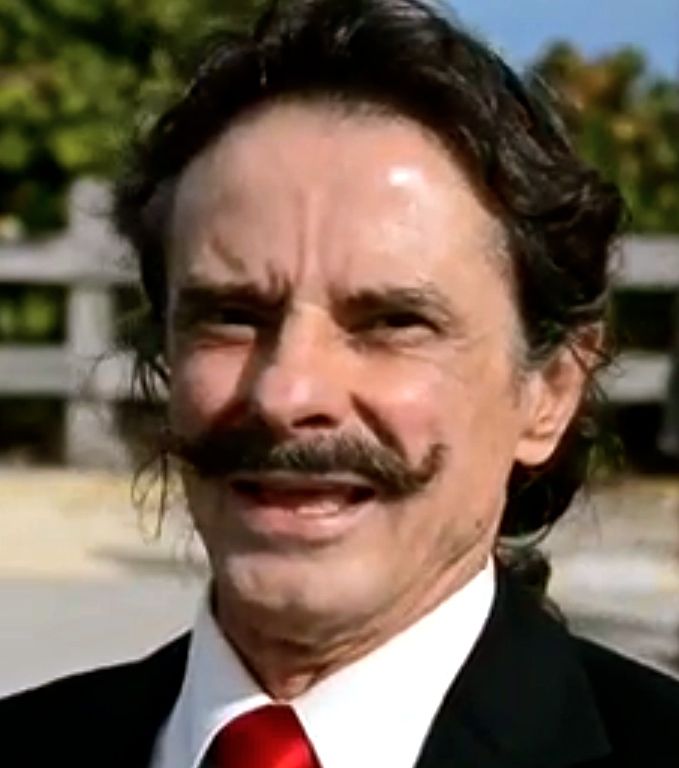

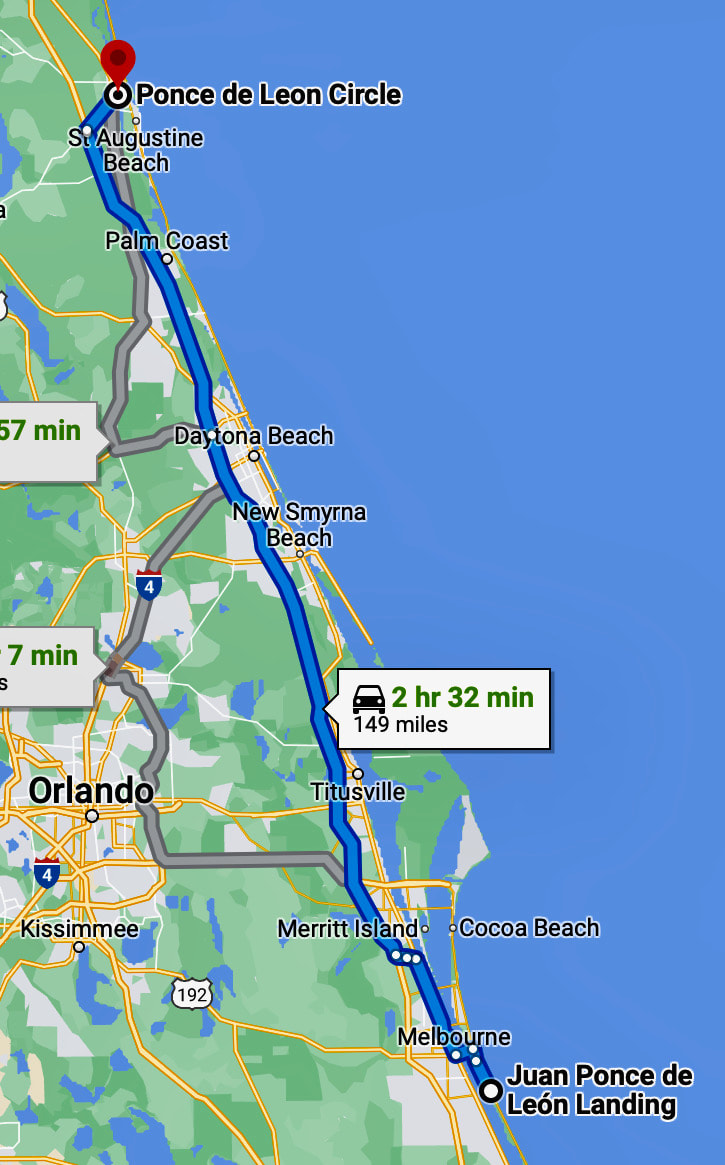

The dream of marking the spot where Juan Ponce de Leon actually landed — after discovering and naming Florida 500 years ago — finally was realized Saturday, Dec. 28, 2013, as more than 100 people gathered in Melbourne Beach, Fla., for the unveiling of an impressive 10-foot, bronze statue of the Spanish conquistador holding a cross and facing the Atlantic Ocean. The statue officially marks Melbourne Beach's claim that de Leon first landed there instead of St. Augustine some 125 miles north, where it was long believed the first landing took place. It took many years of work and sacrifice by a small group of very passionate history buffs, but they were able to prove that distorted history could be corrected and made relevant once again. They marked the site where Florida began and this country was born, and they created a huge source of pride for Hispanics! The effort was led by Samuel Lopez, a New York Puerto Rican who relocated to Melbourne Beach and spent a dozen years making sure his childhood idol de Leon finally got the recognition he deserves — at the spot where he actually landed. "We thank God that it happened," Lopez told reporters. "It's a national treasure. It's our history." Lopez is a devout follower of the theory established by historian and navigator Douglas T. Peck, who retraced de Leon's 1513 journey in the spring of 1990 and found that landfall on Florida's east coast occurred much farther south than what historians had been telling us. Although the de Leon expedition's original log has never been recovered, and historians can only go by a 1601 copy transcribed by Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera, Peck set sail from Puerto Rico, piloting a 33-foot cutter with the same specs as a Spanish caravel, and determined that instead of the "celestial navigation" historians had assumed was used in 1513, the expedition was guided by "dead reckoning," a process of calculating a ship's position based on its course, speed and time from its point of origin. Anton de Alaminos, the pilot of de Leon's expedition, had learned "dead reckoning" from Christopher Columbus, Peck argued, and had stuck with it when he guided de Leon to Florida. This process, combined with adjustments for flaws in 16th century compasses, led Peck to conclude that the latitudes reported for the 1513 landing were off by two degrees to the north. Even with modern navigational technology, Peck found that the speed of de Leon's three ships did not have the time to reach as far north as St. Augustine. His controversial findings, published in the Florida Historical Quarterly in 1992, ignited a debate among historians and created a rivalry between two cities that culminated on April 2 and 3 of 2013, when both Melbourne Beach and St. Augustine hosted 500th anniversary reenactments of de Leon's landing. Surely, some people feel that a Melbourne Beach landing site threatens the tourism industry in St. Augustine, which has not only benefited from being the nation's oldest city (established in 1565), but from claiming to be the location of de Leon's landfall in 1513. One of its main attractions is the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, where tourists are still told de Leon landed. Yet Peck's findings have become much more widely accepted in recent years, thanks to the tireless persistence of Lopez and a few other Central Florida Hispanic community activists who have sought support from other historians and insisted on correcting distorted American history in their part of the country. Using the lobbying and fundraising resources of three Hispanic organizations — the Florida Puerto Rican/Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, the United Third Bridge civil rights group and the reenactors of the Royal Order of Juan Ponce de Leon — Lopez has been trying to put Melbourne Beach on the history maps for many years. In 2005, he got the county to designate a small strip of public beach — on State Road A1A, just south of the Melbourne Beach city limits — as Juan Ponce de Leon Landing Park. Then he raised the funds, mostly through private donations, to hire Spanish sculptor Rafael Picon to begin building the statue. But when only a black granite pedestal was revealed at the statue's originally scheduled unveiling on April 2, some people began to question whether Lopez's dream would ever be realized. He was still $67,000 short of the amount needed to finish the project. Yet Lopez persisted. On this same day when he had no statue to show the public, Lopez hosted Dr. Michael Gannon as the keynote speaker at a special Melbourne Beach mass to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Ponce de Leon's great discovery. And Gannon, the retired University of Florida professor considered the dean of Florida historians, threw his immense reputation behind Peck and the Melbourne Beach landing theory. He said Peck's voyage represents "the latest and best evidentiary statement we have on the Juan Ponce landing," and his embrace of the Melbourne Beach theory may have served as the leverage Lopez needed to finally convince county officials to help him pay for the statue. When Lopez argued that the statue would become a tourist attraction, the Brevard County Tourism Development Council unanimously agreed to use hotel room tax funds to pay the $67,000 needed to complete the project. And so when the new de Leon statue finally was unveiled, and a group of Central Florida Hispanic community activists realized their shared dream, we learned how people can make a difference, how history can be corrected and how America's hidden Hispanic heritage can be rediscovered. Bravo! |

En español

|

UPDATE FROM MY 2022 ROADTRIP

|

Please share this article with your friends on social media: