54. Galveston: Still the Isle of Misfortune?

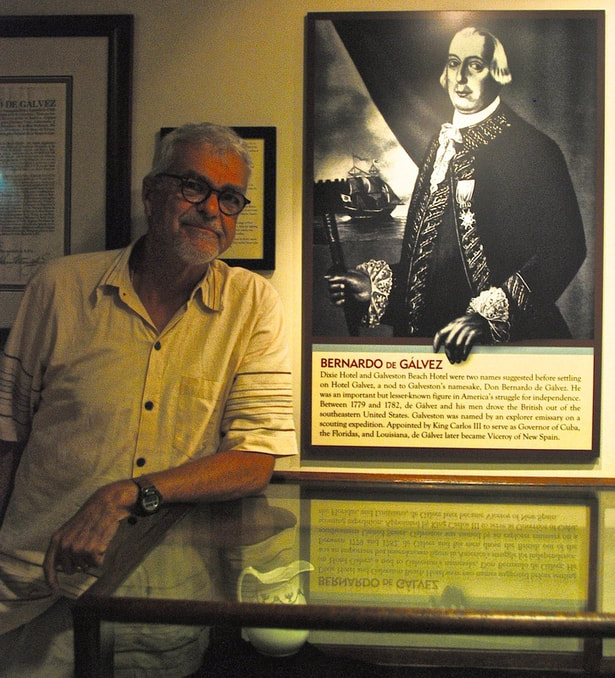

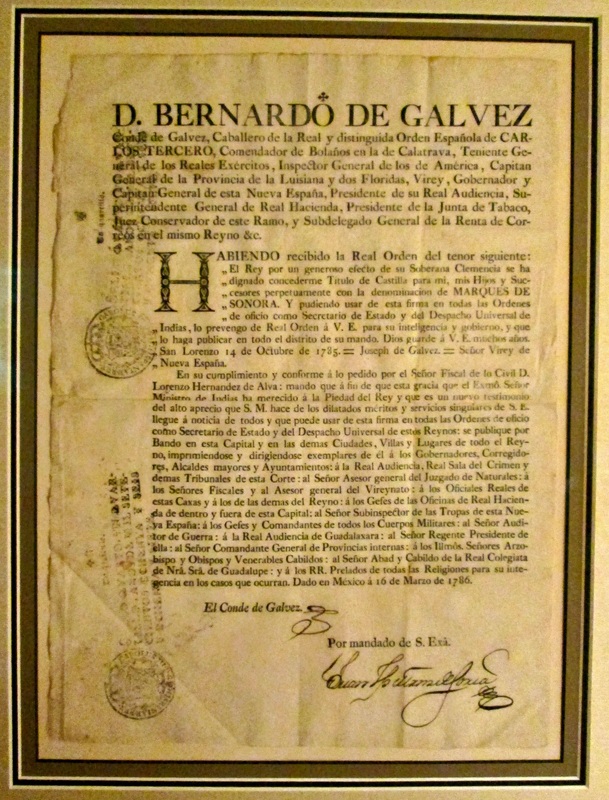

|

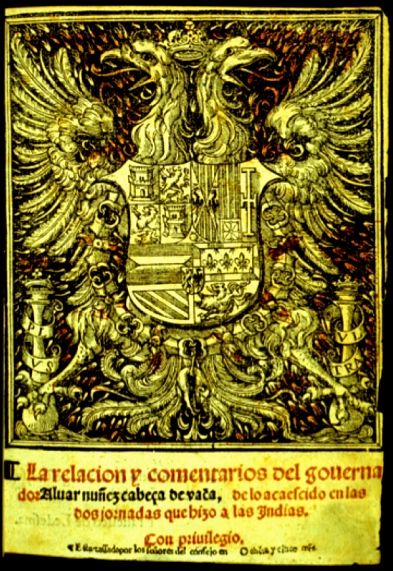

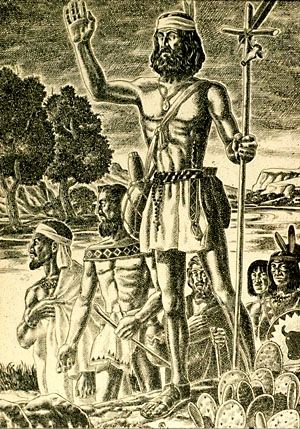

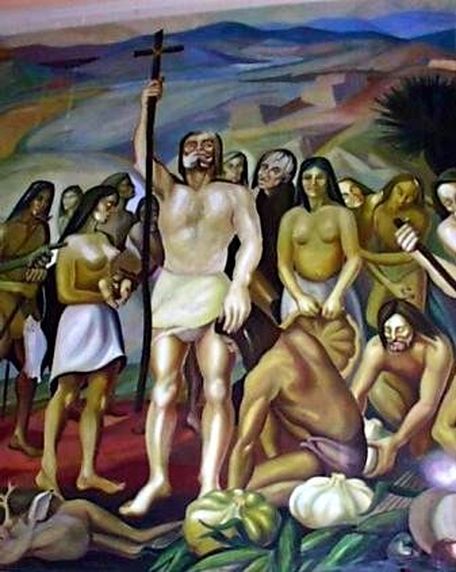

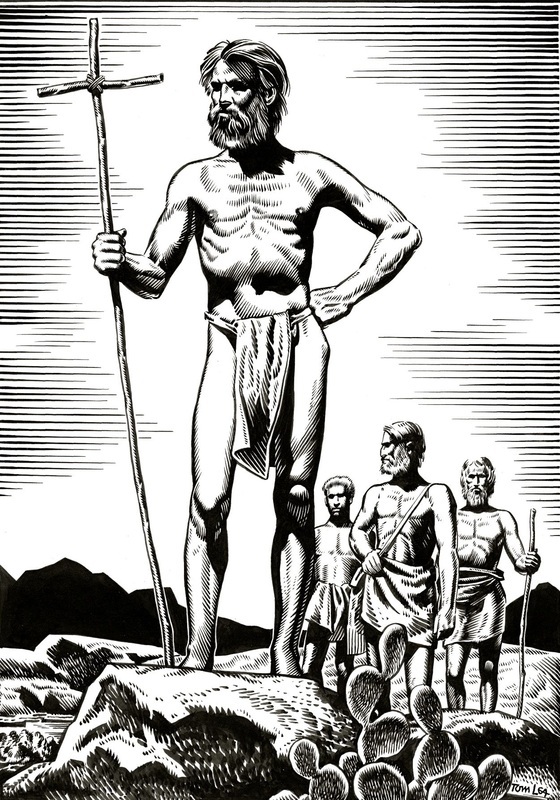

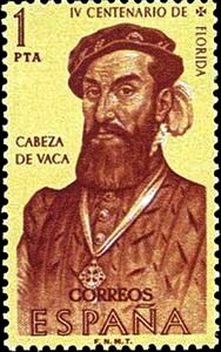

By Miguel Pérez

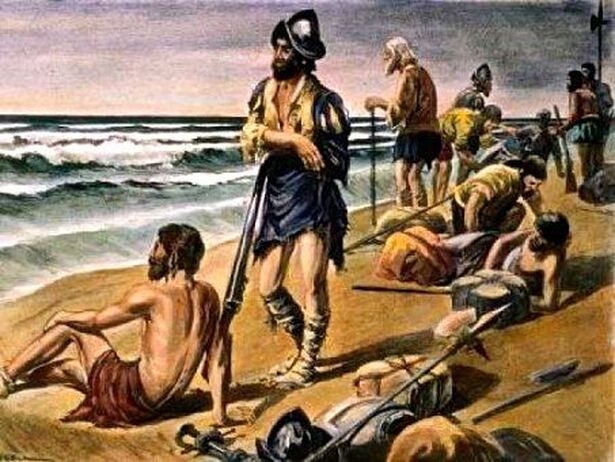

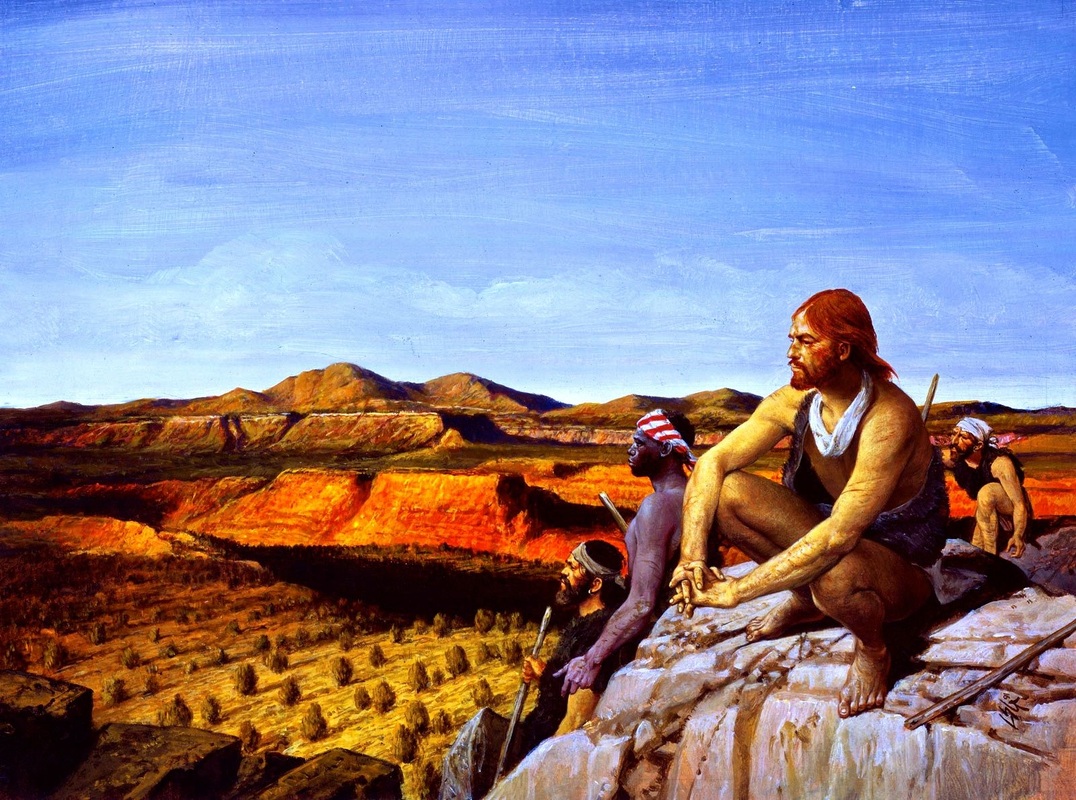

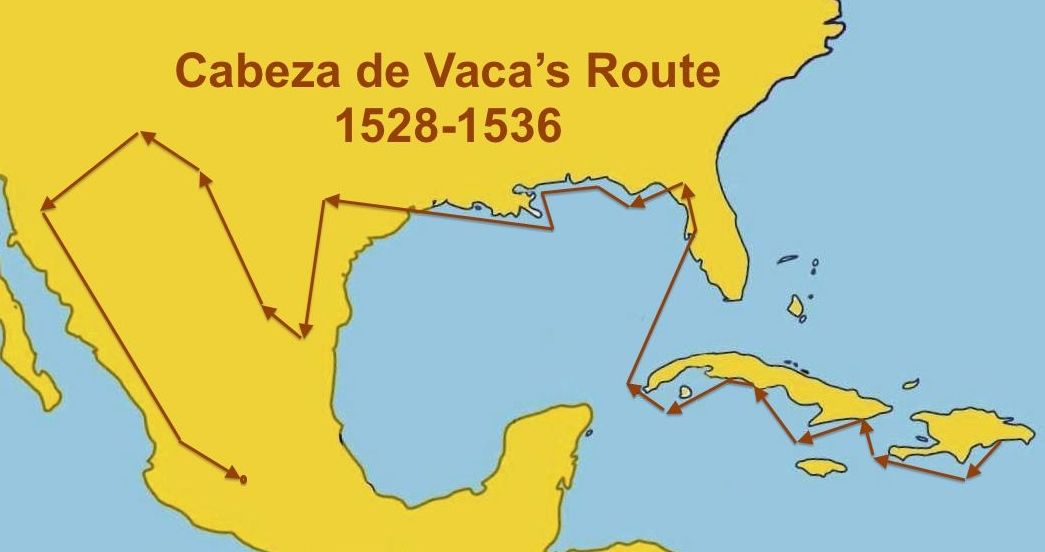

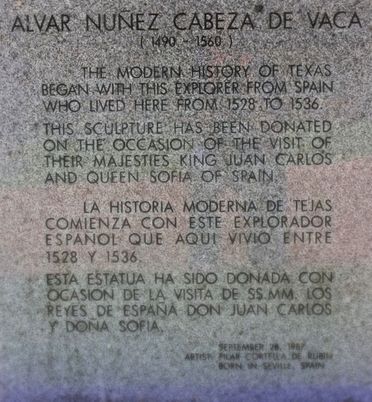

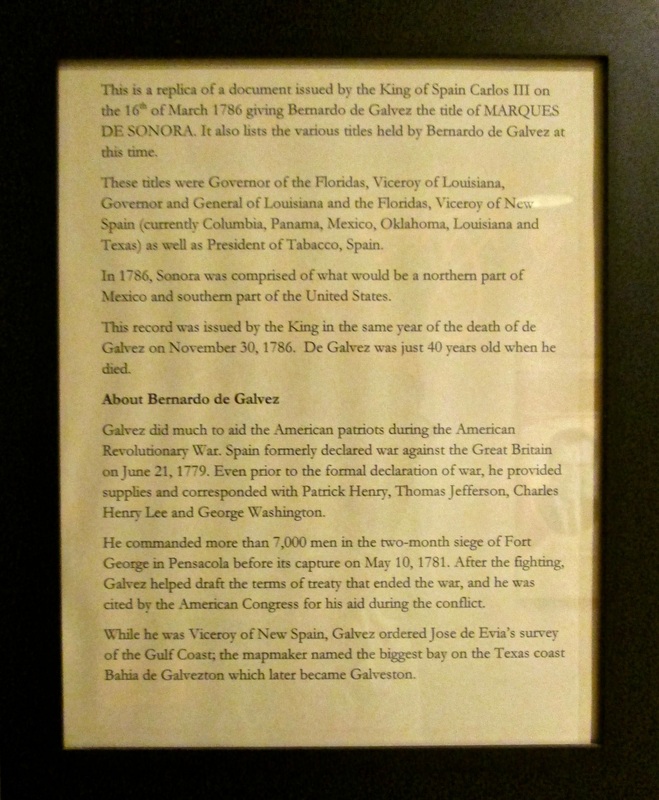

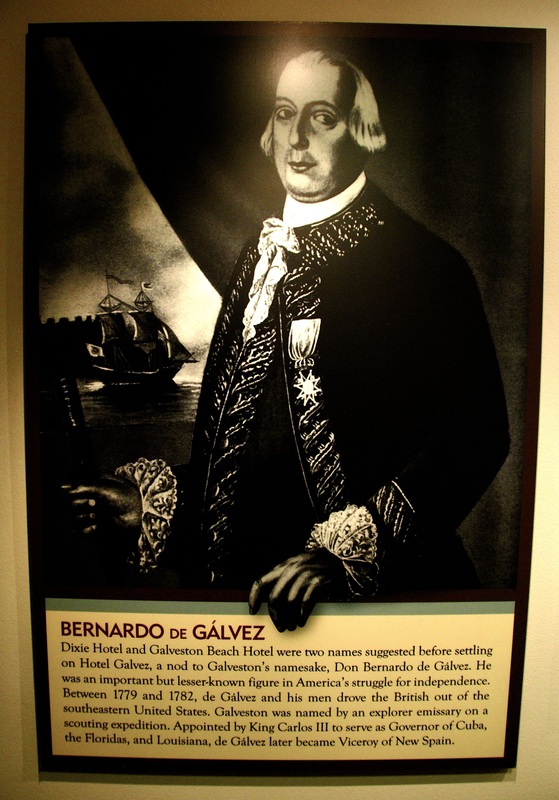

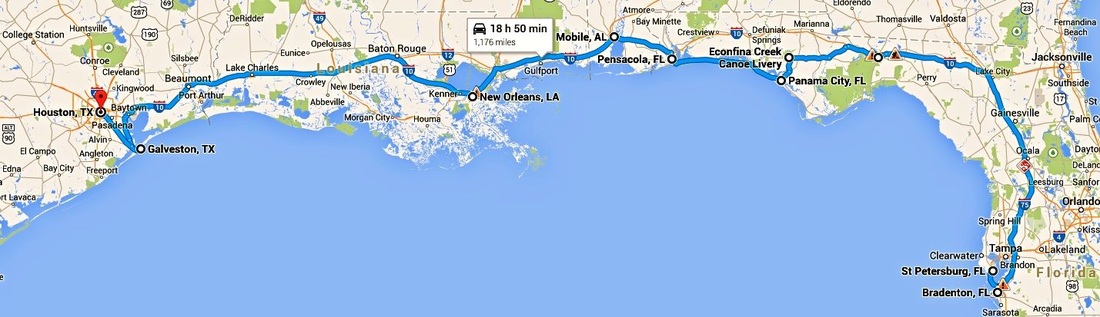

July 29, 2014 - As if the day had been made to order, just for me to truly appreciate the hardships endured by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and a few-dozen other shipwrecked Spanish conquistadors almost 500 years ago, there was menacing weather when I arrived on Isla de Mahaldo — the Isle of Misfortune. Nowadays they call it Galveston Island, Texas, but I could clearly see why the Spanish gave it its former name. The rain was pouring, the waves were rough, the wind shook my SUV, and the visibility was so poor that I didn't really see or appreciate today's City of Galveston and its beachfront attractions. What I saw was how terribly inhospitable that corner of the world can still be and how nature must have battered the Spanish castaways who were trapped there — some for more than a year — serving as slaves to the natives of the island. And yet, as much as I looked, in spite of the stormy weather, I found no markers explaining that this is believed to be the place where Europeans first stepped on Texas. I saw no statues of Cabeza de Vaca, no plaques mentioning his name, no apparent interest in promoting the city's hidden Hispanic heritage. But this is Galveston, you say. The island, the bay, the county and the city are named after American Revolutionary War hero Bernardo de Gálvez. And yet even tributes to the city's eponym are hard to find in Galveston. At the grand old Hotel Galvez, you see an impressive oil portrait of Gálvez and a brief explanation about how the hotel got its name: "He was an important but lesser-known figure in America's struggle for independence. Between 1779 and 1782, de Galvez and his men drove the British out of the southeastern United States." The hotel's Hall of History exhibit also notes that after the American Revolution, when he was the viceroy of New Spain, Galvez commissioned a survey of the Gulf Coast and that it was mapmaker José de Evía who named the biggest bay on the Texas coast "Bahía de Galvezton," which later became Galveston. But with two huge Hispanic figures in its history, I expected to see much more Hispanic heritage in Galveston. Perhaps it has something to do with a museum, once considered "the hub of Galveston County history," having been shut down by Hurricane Ike in 2008. Although the Galveston County Museum's artifacts and exhibits were saved from damage, they have been displaced to smaller galleries in several locations, including the Galvez Hotel. Yet what you see there is mostly an exhibit of the hotel's history and the famous 20th-century people who have stayed there. The island's Hispanic heritage seems to have been washed out by the storms and lost with time. After visiting towns like Pensacola, Florida, and New Orleans, where I was surprised to see Hispanic heritage still is promoted, Galveston was a disappointment. The Spanish name for the island still seems appropriate. Some background: After losing more than 200 of their shipmates while trekking westward along the Gulf Coast all the way from the Tampa Bay area, this is the Texas offshore island where, many historians believe, a few-dozen remaining survivors of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition became castaways and captive in early November of 1528. While Narváez had already been lost at sea prior to their arrival in Texas, this is the island where many others died. Many drowned while trying to reach the mainland, and others succumbed to hardship, hunger, disease, slavery, executions and even cannibalism. "In a very short time," Cabeza de Vaca reported, "only 15 survivors remained of the 80 who had arrived there ... We named this island the Isle of Misfortune." Of the 15 who managed to flee the island, only four of them, including Cabeza de Vaca, managed to cross present-day Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, and to rejoin with Spanish forces in New Spain (present-day Mexico) in 1536. Cabeza de Vaca went back to Spain and wrote "La Relación" — Spanish for "The Account" — narrating the nearly eight years he spent trekking across North America and living among the natives — from present-day Florida to Arizona and Mexico. Although it was written in Spanish and first published in Spain in 1542, "La Relacion," with its fascinating accounts of the first contacts between Europeans and Native Americans, should be considered the first American history book. Although it was originally prepared as a report for the king of Spain, "La Relación" — also published later as "Naufragios" ("Shipwrecks") — was written like an adventure novel and sparked the imagination and ambition of many other Europeans. It was through his narrative that Europe first learned about the customs of the Native American way of life. His fascinating accounts of their meager subsistence, sources of food, family life and even same-sex marriage sparked interest throughout the Old World. In spite of the hardships he endured in Galveston and throughout his epic journey, Cabeza de Vaca's book inspired other Europeans to come to North America to seek fame, fortune and mythical cities of gold. It triggered other explorer expeditions and ignited a Hispanic migration to North America that has continued for almost 500 years. Having trekked across the North American wilderness — some 276 years before Lewis and Clark — and having written his own narrative of the journey, Cabeza de Vaca could be considered the first European American author, historian, geographer, ethnologist, merchant and even medicine man. Having preached the Gospel of Christ across the Southwest, he was also America's first evangelical preacher. And yet I found no mention of this in Galveston. While the accomplishments of other Spanish conquistadors are recognized in other parts of the country, especially Juan Ponce de León, Hernando de Soto and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, and after reading the work of so many historians who believe Galveston is indeed Mahaldo, naturally I was expecting Galveston to recognize Cabeza de Vaca and his shipmates in some significant way. Yet on Galveston Island, all I found was a short, dead-end street called Cabeza de Vaca. But let's blame it on bad weather, a hurricane-battered museum and poor visibility, and give Galveston the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps, on a sunny day, and when the Galveston County Museum reopens at a new site "in late 2014," the island's hidden Hispanic heritage can still be rediscovered. I'll have to go back! However, since my Great Hispanic American History Tour needed to keep moving west, and since I knew of a Cabeza de Vaca monument in Houston, I went back to the mainland only to discover that his bust, in Houston's Hermann Park, has been temporarily removed while the park is under reconstruction. Park visitors no longer can see the bust or its inscription, which noted, "The modern history of Texas began with this explorer from Spain who lived here from 1528 to 1536." Did I mention our hidden Hispanic heritage? I'll have to go back there, too. But now that we are in Houston, next week this tour and this column must make a stop at the San Jacinto Battle Monument and Museum, where Texas won its independence from Mexico and where there is hidden Hispanic heritage and historical misconceptions that need to be exposed and explained. COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM |

To enlarge these photos, click on them!

|

Please share this article with your friends on social media: