70. If They Knew Arizona's History,

They Wouldn't Be So Xenophobic

|

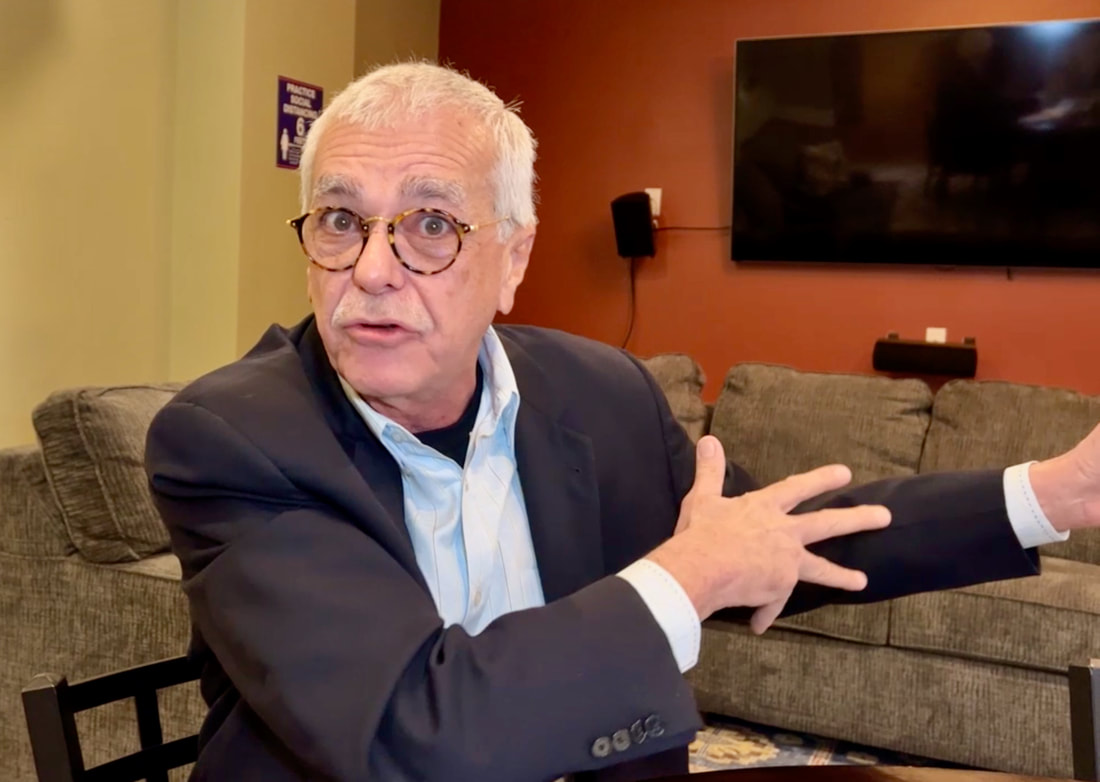

By Miguel Pérez

November 18, 2014 - The first time I met him, I immediately perceived that he had a unique talent for bringing Hispanic American history into present-day context. And that's all I needed. Because my history columns seek the same objective, I became an instant fan and follower of Dr. Bernard "Bunny" Fontana. It was more than two years ago, and we were in the living room of his Sonoran Desert home, just outside the Tohono O'odham Native American reservation in southern Arizona — the area he has explored, researched and exposed in several books as a noted anthropologist and historian. It was there where he explained that the country has the wrong image of Arizona, a negative, anti-immigrant image created and projected by loudmouth Arizonans, who tend to be recent arrivals from other parts of the country — carpetbaggers — and don't know the state's history of welcoming immigrants from Mexico or even recognize that the state once was part of Mexico. Wanting to know more about that history and how it is ignored by today's politicians, my Great Hispanic American History Tour made another stop at Bunny Fontana's living room — now relocated in an assisted living facility in Tucson. He was as gracious, witty, knowledgeable and dynamic as the first time I met him. And just as outspoken, too. "Not only do they not know the history, they don't know the culture," Fontana said. "And they are terrified. It's the unknown. I mean, they have all these stereotypic images of Mexico. Violence, crime, corruption — you know the list. ... So you have real xenophobia taking place." No, he doesn't pull punches. Whereas central and northern Arizona are mostly populated by people who came from other states one or two generations ago, Fontana said most southern Arizonans have been there for many generations, understand the state's history much better and are considerably more tolerant of new immigrants crossing the border from Mexico. "By and large, Tucson and southern Arizona generally have managed to maintain this consciousness of this history, and it really is a radically different attitude, taken in sum total, between here and north of the Gila River," he said. Unfortunately, he said, the image projected to the rest of the nation is coming out of central and northern Arizona, especially Phoenix. Most people who live in southern Arizona, more specifically in Gadsden Purchase territory, are well aware that Mexicans didn't go to the United States but that the United States came to them. Arizona was once a well-balanced mixture of Native Americans, Mexicans — including "layers of new immigrants who kept coming up all the time" — and Anglo-Saxons, Fontana explained. "And that's somewhat threatened in recent times because ... we've had a much heavier influx of people from elsewhere pouring not only into Maricopa County but moving into this area, as well. And so we've ended up with class division." He said that though the Hispanic community further north in Maricopa County probably feels more threatened than southern Arizona because of the county's immigrant-bashing sheriff, Joe Arpaio, Tucson Latinos also have been protesting against racial profiling by local cops in search of undocumented immigrants. Fontana — who spent more than three decades doing research and field work, as well as writing and teaching, at the Arizona State Museum and University of Arizona Libraries — is not fazed by the right-wing propaganda and media hype on every new wave of immigrants, because he puts it all in a historical context. "You know, the real history of this place, the long history, is not the east-to-west movement that they are still teaching in schools all over the country," he said. "It's more south to north. That's been going on for a long time, and it obviously hasn't stopped as of this moment, because we have a whole bunch of little kids from Latin America now in facilities here all over the place. So this is simply the 2014 version of something that has been going on for a long time." Fontana is a strong critic of the immigration checkpoints that have been set up by the U.S. Border Patrol on U.S. highways far north of the border with Mexico. "They are violating everyone's constitutional rights," he said. "They seem to be completely above and beyond the law with everyone. I mean, it's scary. It's really frightening. It's like we've lost control of our own government. This used to be the land of the free and the home of the brave, but it's not either one anymore." He is a supporter of demonstrators who have been asking for the checkpoints to be removed. "They are over there with literature, handing it out to anybody who comes driving along, telling them what all their rights are, that they don't have to answer all these questions if they don't want to — especially if someone asks, 'Where have you been?' Just tell them it's none of their business. I mean, this is insane!" What I like most about my friend Fontana is that he doesn't mince words, especially when he explains that we Hispanic Americans have to learn to accept who we are as a people — even if it means recognizing that some of our ancestors were cruel and unfair. |

"Let's face it; (New Mexico conqueror Juan de) Oñate was crueler than hell," he said. "Just like what's going on now with these people who chop heads off and arms off without a blink. That's what they did to the Indians at Acoma (New Mexico). They cut off the left foot of every adult male. They killed about 800 men, women and children. They took the women and kids and shipped them off to southern Mexico. It was a real atrocity by any measure, and you can't justify it by saying, 'Well, those were the times. We can't judge them by modern (standards).' ... It was an atrocity then as it would be an atrocity now. It was just awful. Needless to say — to the Indians, the Acomas, especially — this is firmly fixed into their knowledge and stories and tradition."

But Fontana also recognizes the great contributions Spanish explorers made to North America — even the cruel ones. "This is one of those horns in the dilemma," he said, "because to all the Hispanos in New Mexico, after all, there is no denying it; they wouldn't be there if it hadn't been for Oñate. I mean, he was the founder. He was the one who really brought Europe and made it stick. In New Mexico, he brought in this whole culture along with him."

So though Hispanic American history has some "terrible, brutal parts," we should also note that "we are who we are today, all of us, because of it — whether we like it or not."

"It's like the dilemma we have in the United States," he said. "You know, we took the land away from the Indians, and there is no way of denying it."

In his book "Entrada: The Legacy of Spain and Mexico in the United States," Fontana masterfully and objectively outlines both the achievements and the shortfalls of the Spanish conquest of North America — from the brutality to the great discoveries.

We have so much in common, so many anecdotes to share, that it was hard to say goodbye to my friend Fontana. As I kept saying adios, we kept sharing stories about historical landmarks we have both visited and historical figures we both admire or abhor. We spoke of our mutual disdain for politicized school administrators and government bureaucrats who ban books about Hispanic heritage.

I told him that East Coast Latinos know very little about Southwest Hispanic history, and he told me Southwest Latinos know practically nada about St. Augustine, Florida.

We had a good laugh about two Republican gubernatorial candidates who were competing on TV commercials to show who could be more ignorant and insensitive, not only to undocumented immigrants but to the Arizonans who support them. And we had to chuckle when we compared notes on the ultimate immigration checkpoint screw-up: A Latino in his 90s was held in the desert heat for more than an hour, apparently suspected of being here illegally — although the man was former Arizona Gov. Raul Castro, who also was a U.S. ambassador to several countries. This was racial profiling at its worst!

Fontana suggested numerous must-see stops for the Great Hispanic American History Tour — all the way up to a glacier discovered and named by Spanish explorers in Alaska. And he told me I couldn't leave Tucson without visiting the downtown Spanish presidio. "They have restored a chunk of the old presidio," he said, still excited about history. "I mean they rebuilt it on the foundations. They have a wonderful program down there. They even fire off a cannon on the weekends."

Do we have a choice? Next week, the Great Hispanic American History Tour visits that presidio.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM

But Fontana also recognizes the great contributions Spanish explorers made to North America — even the cruel ones. "This is one of those horns in the dilemma," he said, "because to all the Hispanos in New Mexico, after all, there is no denying it; they wouldn't be there if it hadn't been for Oñate. I mean, he was the founder. He was the one who really brought Europe and made it stick. In New Mexico, he brought in this whole culture along with him."

So though Hispanic American history has some "terrible, brutal parts," we should also note that "we are who we are today, all of us, because of it — whether we like it or not."

"It's like the dilemma we have in the United States," he said. "You know, we took the land away from the Indians, and there is no way of denying it."

In his book "Entrada: The Legacy of Spain and Mexico in the United States," Fontana masterfully and objectively outlines both the achievements and the shortfalls of the Spanish conquest of North America — from the brutality to the great discoveries.

We have so much in common, so many anecdotes to share, that it was hard to say goodbye to my friend Fontana. As I kept saying adios, we kept sharing stories about historical landmarks we have both visited and historical figures we both admire or abhor. We spoke of our mutual disdain for politicized school administrators and government bureaucrats who ban books about Hispanic heritage.

I told him that East Coast Latinos know very little about Southwest Hispanic history, and he told me Southwest Latinos know practically nada about St. Augustine, Florida.

We had a good laugh about two Republican gubernatorial candidates who were competing on TV commercials to show who could be more ignorant and insensitive, not only to undocumented immigrants but to the Arizonans who support them. And we had to chuckle when we compared notes on the ultimate immigration checkpoint screw-up: A Latino in his 90s was held in the desert heat for more than an hour, apparently suspected of being here illegally — although the man was former Arizona Gov. Raul Castro, who also was a U.S. ambassador to several countries. This was racial profiling at its worst!

Fontana suggested numerous must-see stops for the Great Hispanic American History Tour — all the way up to a glacier discovered and named by Spanish explorers in Alaska. And he told me I couldn't leave Tucson without visiting the downtown Spanish presidio. "They have restored a chunk of the old presidio," he said, still excited about history. "I mean they rebuilt it on the foundations. They have a wonderful program down there. They even fire off a cannon on the weekends."

Do we have a choice? Next week, the Great Hispanic American History Tour visits that presidio.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM

Please share this article with your friends on social media: