67. Hiking In Search of Coronado's Trail

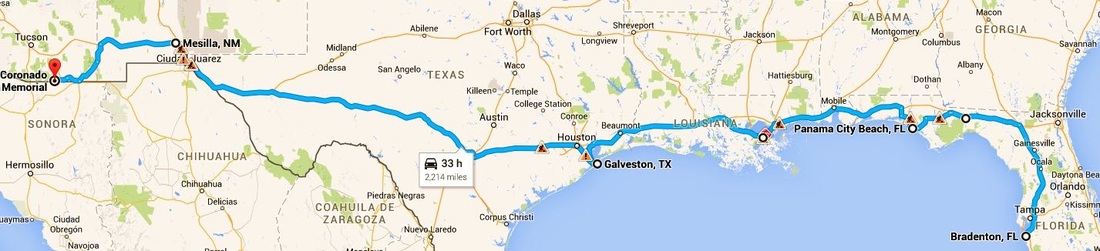

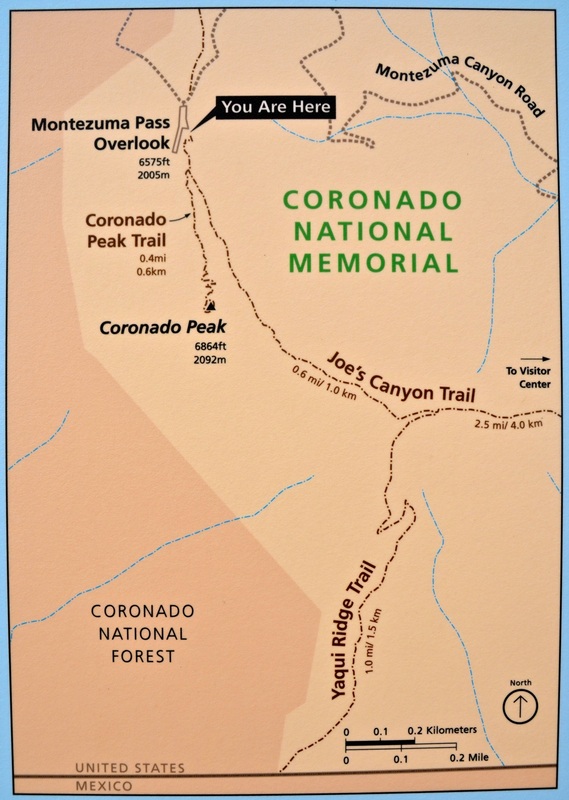

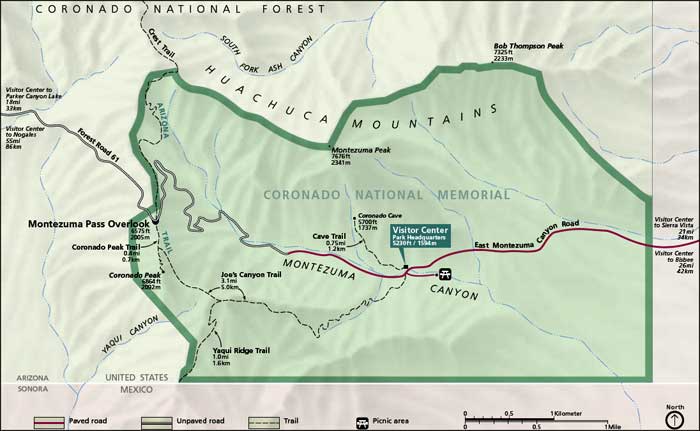

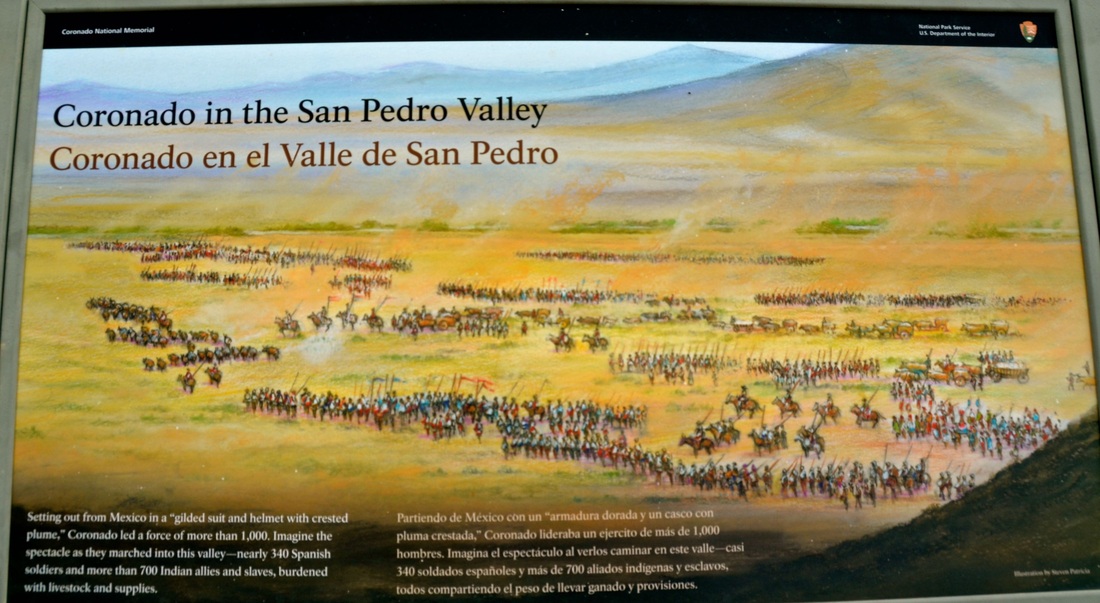

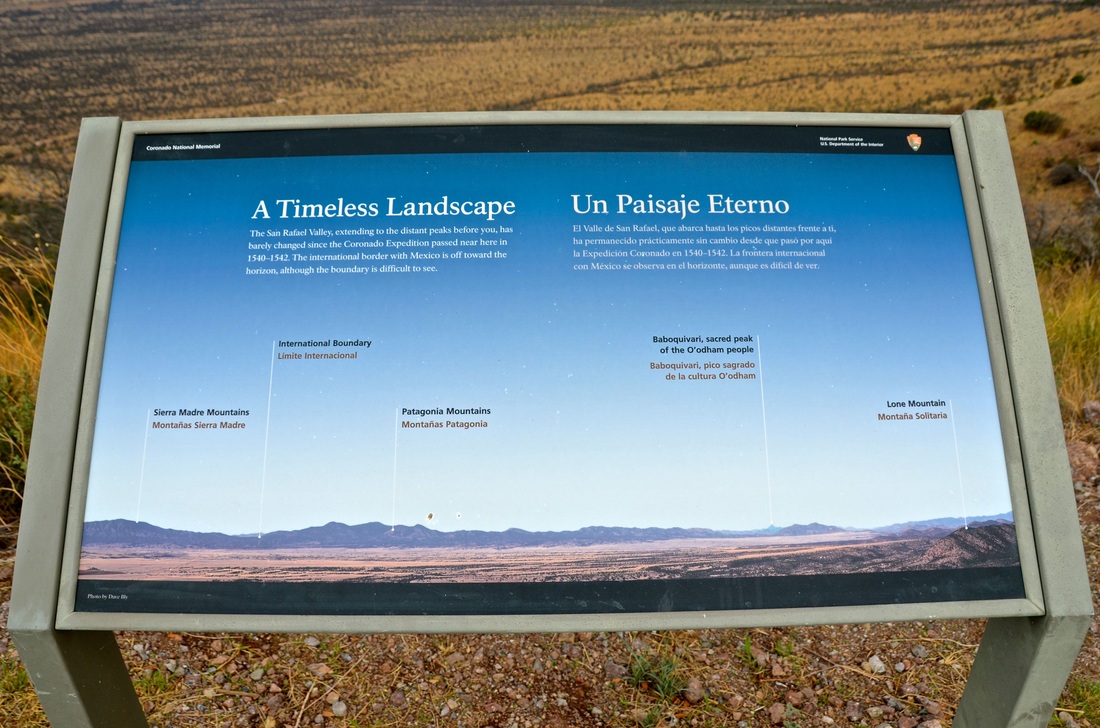

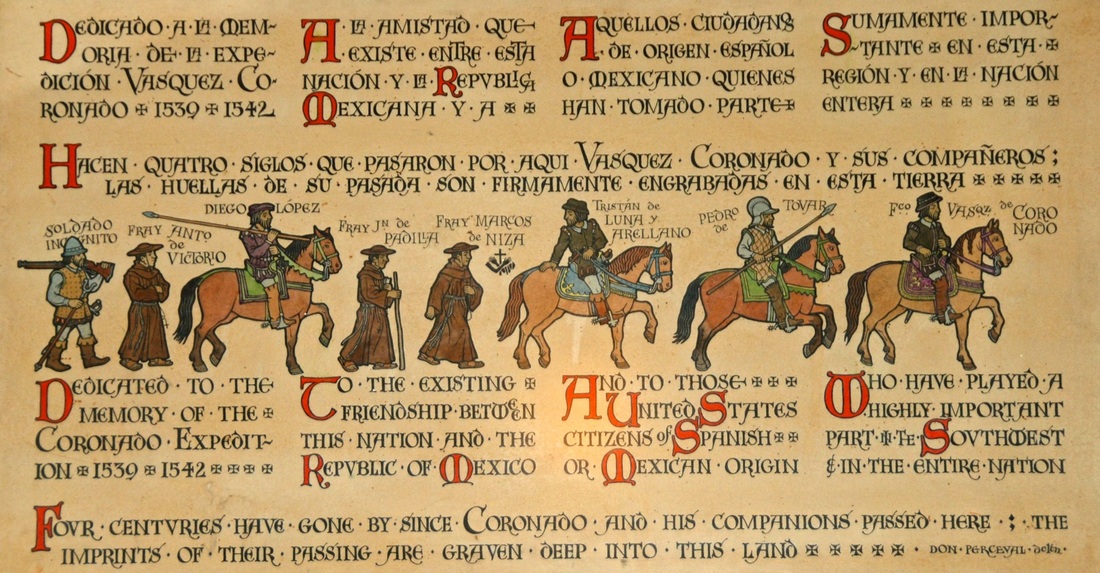

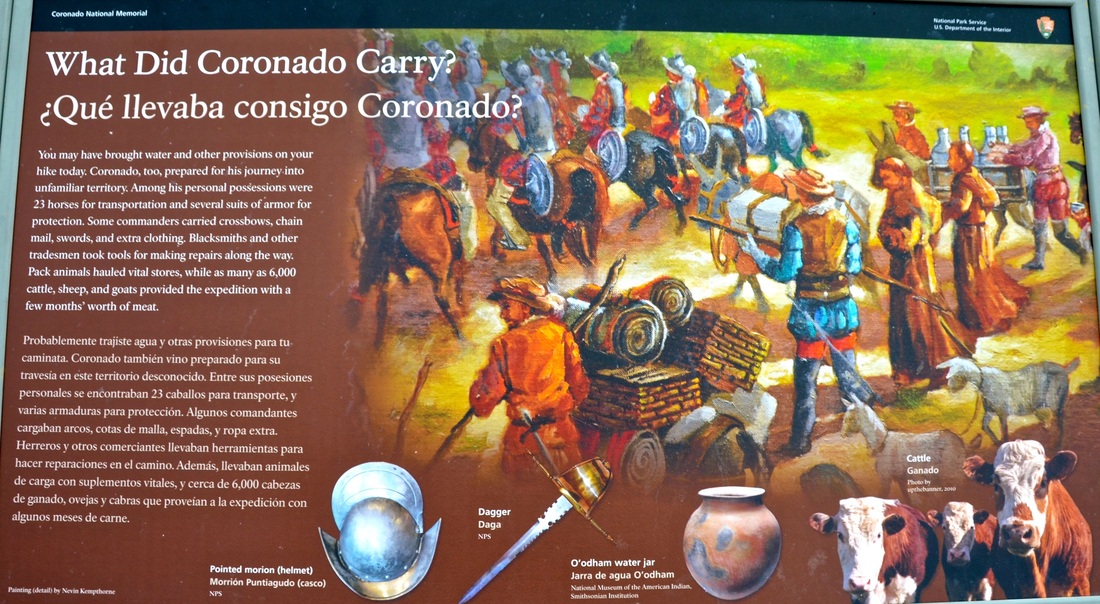

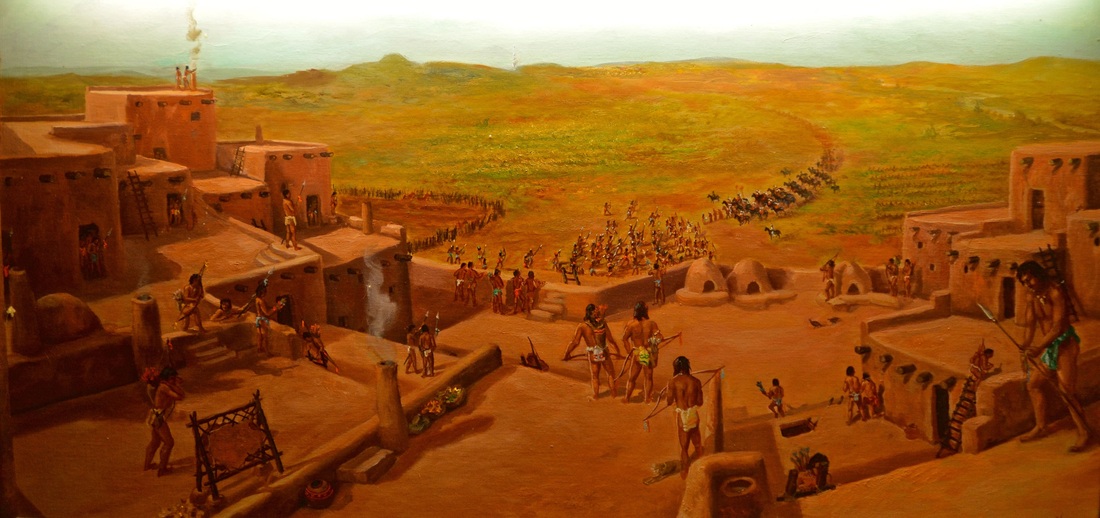

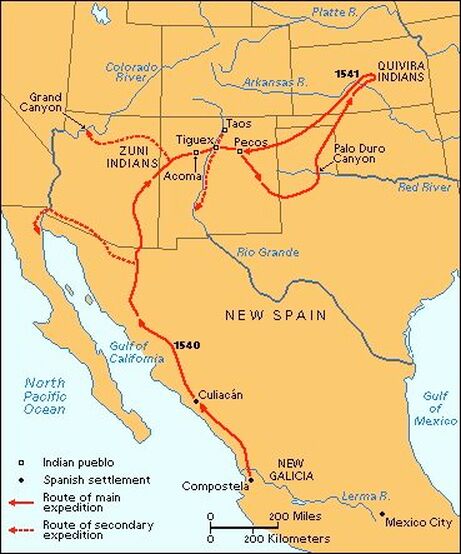

|

By Miguel Pérez

October 28, 2014 - As you drive there, you get the feeling you are terribly alone. The area is so remote and desolate that if you are traveling by yourself, it feels a little spooky, like being on a deserted planet. You don't see anyone for miles! You've driven across the country to visit the Coronado National Memorial in southern Arizona, which commemorates the 1540 to 1542 Francisco Vasquez de Coronado expedition through North America and "the cultural influences of Spanish colonial exploration." But you are greeted by signs warning you that if you are traveling alone, you shouldn't be there. "WARNING: Smuggling and/or illegal entry is common in this area due to the proximity of the international border," the signs say. "Please be aware of your surroundings at all times and do not travel alone in remote areas." "But I'm already here," I shouted, as if anyone was listening. "It's too late to turn around, isn't it?" The Great Hispanic American History Tour began at the De Soto National Memorial in Bradenton, Florida, and visiting the Coronado National Memorial in was imperative. Both are well-operated by the National Park Service, and both teach visitors important Hispanic American history lessons. The one in Arizona, however, requires a little more bravado. Other signs warn you to carry plenty of water when hiking, to protect yourself from the scorching sun, to look out for monsoon thunder and lightning storms that "often lead to flash flooding," and to be alert on walking trails, "as poisonous snakes may be encountered." But other than that, you're fine. Flanked by Arizona's Huachuca Mountains to the north and the U.S.-Mexico border to the south, the Coronado National Memorial covers 7,423 square miles of rugged terrain — arid mountains and valleys covered by desert grasses and shrubs, with steep dirt roads and hiking trails. But at the memorial's visitors center — and on its mountaintops — you get great history lessons. After all, this park's location was chosen because of its panoramic views of the San Pedro Valley, which is the route believed to have been taken by Coronado when he led "one of the greatest land expeditions the world has known," from present-day Mexico through today's Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. From the park's Montezuma Pass, a 6,575-foot mountaintop overlook — attainable by four-wheel-drive vehicles and daring drivers — you can see a huge section of the U.S.-Mexico border and the valley where the Coronado expedition first entered what is now the United States. The only people I found on Montezuma Pass were several U.S. Border Patrol agents, who were keeping a lookout on the entire area. Times have changed! Yet from up there, it is easy to envision that huge caravan of explorers coming north in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, which were said to possess great wealth but had only been seen from a distance by other Spanish explorers. It happened 474 years ago, but the terrain probably looks exactly the same. "Coronado led a force of more than 1,000," a historical marker explains. "Imagine the spectacle as they marched into this valley — nearly 340 Spanish soldiers and more than 700 Indian allies and slaves, burdened with livestock and supplies. ... Some commanders carried crossbows, chain mail, swords, and extra clothing. Blacksmiths and other tradesmen took tools for making repairs along the way." It's even easier to envision the Coronado expedition in the park's visitors center, where guests are invited to wear the armor of Spanish conquistadors, huge murals depict the historic journey and a short film — in English or Spanish — tells Coronado's story. At least four priests led the advance party, the exhibit explains, because unlike previous Spanish conquests in the Americas, Coronado had been instructed to conduct "a missionary expedition." The film explains that the expedition had three goals: to find the mythical Cibola, to spread the word of God and to expand the realm of Spain in the New World. "Coronado was intent upon good relations with the Indians and wrote that he would 'try to win them over with good deeds and kindness. But if I should fail, I shall try to do it by whatever means should be more suitable to the service of God and your majesty,'" according to the movie. In fact, he established relations with the friendly inhabitants and got into violent confrontations with those who stood in his way. The park's exhibit explains that "volunteers began departing Mexico City in November 1539 to rendezvous at Campostela, capital of Coronado's province. A final muster of soldiers in February 1540 came to 339, plus wives and servants. ... Several hundred Indians also accompanied the expedition. Approximately 1,500 animals — horses, mules, cows, goats and sheep — completed the assembly. Two ships of supplies commanded by Don Hernando Alarcon sailed along the coast." But the exhibit also notes that "Alarcon's ships failed to make contact with the expedition," that Coronado and his followers were nearly starved when they reached Cibola in present-day New Mexico five months later, and that they were shocked to find that "instead of a great city sparkling with jewels, they beheld a little mud and stone pueblo, 'all crumpled together.'" The expedition continued marching all the way up to the plains of Kansas, with smaller parties of soldiers often assigned to explore in different directions. One of those squadrons of about a dozen horsemen was led by Garcia Lopez de Cardenas, who was assigned to ride westbound across what is now northern Arizona to find "a great river" described by the natives and to see whether it led to Alarcon's ships in the Sea of Cortez, now known as the Gulf of California. They found the river — the Colorado — but it was at the bottom of a canyon from which they found no way to descend. They became the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon. (The Great Hispanic American History Tour already made a stop there two years ago, and their story is at http://www.hiddenhispanicheritage.com/26-the-bucket-list-of-hispanic-heritage.html.) Yet after two years of exploration, Coronado — injured after falling from a horse — was forced to lead the march back to Mexico, without ever finding cities of wealth. "His expedition was deemed a failure," the exhibit explains. "Yet the discoveries — the mouth of the Colorado River by Alarcon, the Hopi villages, the Grand Canyon and pueblos along the Rio Grande — proved more valuable than the gold and silver which eluded him." When he returned to Mexico in 1542, Coronado resumed his position, until 1544, as the governor of the province of New Galicia on Mexico's western coast. He died in obscurity in Mexico City in 1554; because his expedition didn't find the riches it sought, its great achievements were not recognized until many years later. In 1939, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs recognized the 400th anniversary of Coronado's great march and noted, "As a result of this expedition, what has been truly characterized by historians as one of the greatest land expeditions the world has known, a new civilization was established in the great American Southwest." Coronado's notable contributions are based on not just what his expedition found but what it brought to the Southwest, from the horses that changed the lifestyle of nomadic Native Americans to new foods that dramatically improved their nourishment. When reporting to Congress in 1940 on the establishment of the Coronado National Memorial, the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys noted: "Coronado's expedition was one of the outstanding achievements of a period marked by notable explorations. It made known the vast extent and the nature of the country that lay north of central Mexico, and from the time of Coronado, Spaniards never lost interest in the country. In no small measure their subsequent occupation of it was due to the curiosity so created." The park was called the Coronado International Memorial when it was first designated in 1941, but it was officially established as a national memorial by President Harry S. Truman in 1952 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. "The creation of the Memorial was not to protect any tangible artifacts related to the expedition," notes the National Park Service's website, "but rather to provide visitors with an opportunity to reflect upon the impact the Coronado Entrada (entrance) had in shaping the history, culture, and environment of the southwestern United States and its lasting ties to Mexico and Spain." The Great Hispanic American History Tour will hook up with Coronado's trail again, much further north, when instead of Cibola, he begins to search for the land called Quivira, in what today is central Kansas. But next week, as we move further west, we will pick up the 1691 trail of Jesuit missionary Eusebio Francisco Kino, and we'll visit the Spanish missions he established in southern Arizona. To find out more about Miguel Perez and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com. COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM |

|

|

Please share this article with your friends on social media:

|