Hispanic-American History Timeline

Cronología de la Historia Hispano-Americana

By Lehman College CUNY Students

18th Century 1718-1797

|

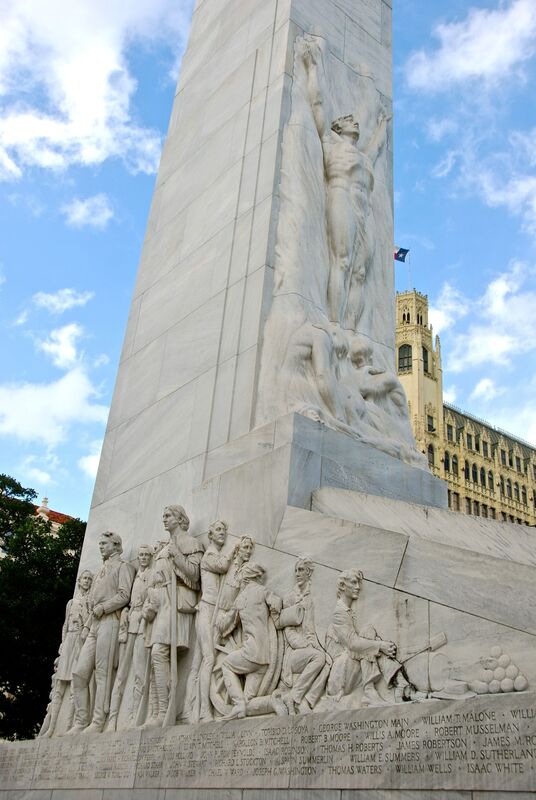

Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares, a Franciscan priest from Andalusia, Spain, treks north from New Spain into present-day Texas and establishes Mision San Antonio de Valero, the Spanish mission that is much better known as The Alamo.

Named after Saint Anthony of Padua, this is the first of five Spanish missions established in East Texas by Spanish Franciscan friars who have received training on how to engage and evangelize the American natives at the Convent of Querétaro, New Spain (Mexico). They are seeking to covert Native Americans to Catholicism and to colonize northern New Spain. After relocating twice until settling at its present site in 1724, just across the river from the town of San Antonio de Bexar -- today's City of San Antonio, Tx. -- the mission becomes self-sufficient, with its own church, granary, living quarters, workshops, fields, and pastures. But in 1836, when it is no longer used as a Spanish mission, it becomes the site of the most famous battle of the Texas Revolution against Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna. After the mission is closed in 1793, the buildings keep changing hands and functions, serving as a meeting place, a hospital and finally a military fort that becomes known as "The Alamo." Occupied by rebels who fight and die for Texas independence from Mexico - including many Hispanics - the Alamo suffers a defeat against the Mexican Army that becomes legendary. "Remember the Alamo" becomes the battle cry that eventually won Texas independence from Mexico. Of the estimated 189 men who die defending The Alamo, only six are actually born in Texas - and all of them are Hispanic: Juan Abamillo, Juan A. Badillo, Carlos Espalier, Gregorio Esparza, Antonio Fuentes, and Andrés Nava. And a man who leaves The Alamo to seek reinforcements and survives, Juan Seguín, is also a Latino. Nowadays, they are all recognized in a monument outside the mission. And The Alamo is San Antonio's biggest tourist attraction, celebrating both its heritage as a Spanish mission and as the sacred battleground of the Texas Revolution. By Adelaida Ospina, Lehman College |

|

|

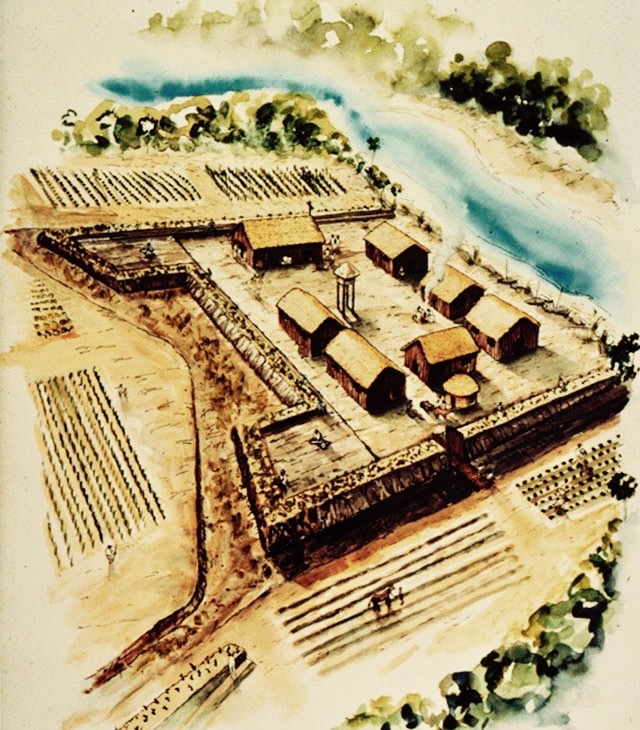

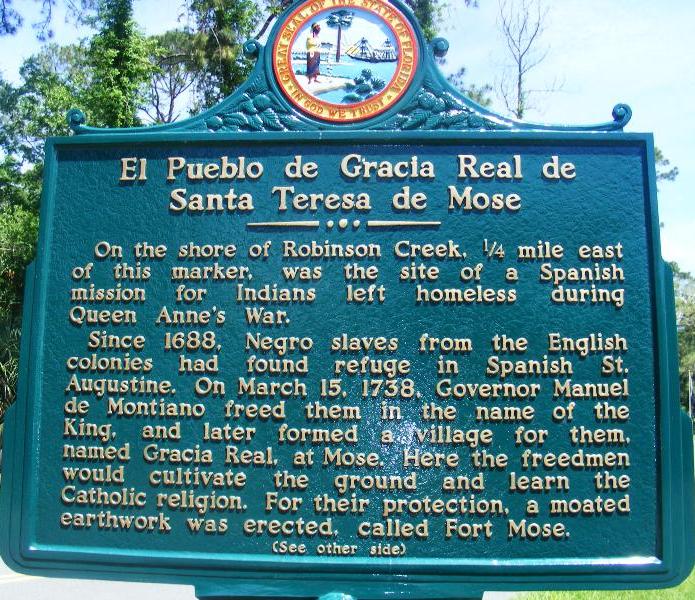

Spanish Florida governor Manuel de Montiano orders the Spanish black militia - composed of runaway British slaves - to build and command a fort for freed African slaves now serving as soldier for the Spanish Crown.

The fort, “Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose” (Royal Grace of St. Teresa of Mose), better known as Fort Mose, is built to defend St. Augustine from British attacks. It becomes the first free African-American community in what is now the United States! "Gracia Real" indicates that the town is established by the king of Spain. "Santa Teresa" (de Aviles) is the town's designated patrol saint, and "Mose" is the name of the area before the settlement. For some 50 years runaway British slaves have escaped from South Carolina and fled to St. Augustine, the capital of Spanish Florida, where they are granted freedom if they convert to Catholicism, agree to serve in the Spanish army and declare loyalty to Spain. One of them is Francisco Menendez. Born in the Mandinka tribe of West Africa, Menendez is brought to British plantations in South Carolina as a slave in the early 1700s. But in 1724, with nine other slaves, he escapes to Florida, regains his freedom, joins Spanish forces, becomes the captain of the black Spanish militia (of former British slaves), and leads the construction of Fort Mose. Built two miles north of St. Augustine, to protect the city against enemy attacks by both land and water routes, the fort attracts other former African slaves who settle outside its walls and create the first free African-American community in North America. Today, Fort Mose is a Florida State Park and U.S. National Historic Landmark where visitors can go back in time to the first African-American settlement. By Melissa Trinidad and Maribel Pantoja, Lehman College NEW DETAILS: See Stop 7 from my summer 2022 road trip: Fort Mose Historic State Park, Fl. The first free African American community — in Spanish Florida! https://www.hiddenhispanicheritage.com/on-the-road-again.html |

|

Spanish soldiers open Fort Matanzas on the east coast of Florida, 15 miles south of St. Augustine, to protect the city from attacks by way of the Matanzas Inlet and the Matanzas River. It is meant to reinforce the city's southern flank and to supplement the security already provided by Castillo de San Marcos, the city's imposing waterfront fort.

Guarding the Matanzas Inlet, which leads to the Matanzas River and the southern waterway entrance to the city, Fort Matanzas has five cannons and adds considerable security, since it allows Spanish soldiers to observe approaching enemy vessels before they can reach St. Augustine. It also serves as rest stop, coast guard station, and a place where friendly vessels heading for St. Augustine get advice on navigating the river. This small, square, supplemental fort - 300 feet high and 50 feet long on each side - took two years to build, and it is made of the same coquina shell-stones that were used to build Castillo de San Marcos. It is manned by a garrison of one officer in charge, four infantrymen, and two gunners, who serve on rotation from their regular duty in St. Augustine. Close to completion, when the fort is challenged by 12 approaching British ships, its cannons force the fleet to retreat without reaching St. Augustine. It is the only time the fort fires cannons against an enemy. The word "Matanzas" (slaughter) refers to a conflict that occurred in that area almost 200 years before Fort Matanzas was constructed. In a war over Florida territory and religions -- Catholics against Protestants -- and in a raid commanded by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, founder of St. Augustine, some 250 French soldiers and settlers had been "slaughtered" there in 1565, giving the name "Matanzas" to the inlet, the river and then the fort. Today, Fort Matanzas stands as a testament to the Spanish empire's determination to protect its territorial claims for control of the New World against the French and British. It was declared a National Monument on October 15, 1924. It is now managed by the National Parks Service, in conjunction with Castillo de San Marcos. Fort Matanzas is normally, open to the public, by way of a ferry. However, ferry access is temporarily closed. By Laedy Lopez, Lehman College |

|

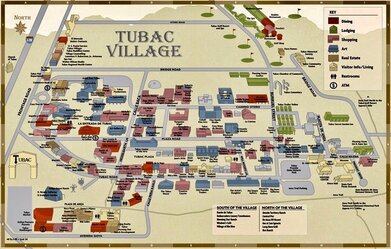

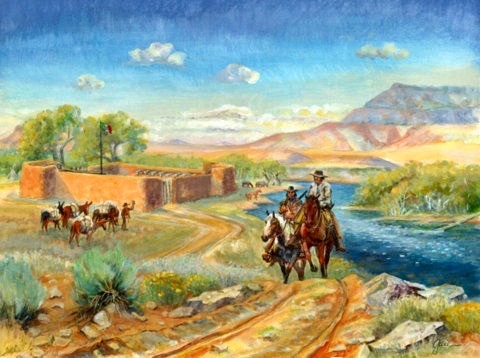

The Presidio of San Ignacio de Tubac, also known as Fort Tubac, is built by Spanish soldiers, becoming the first Spanish colonial garrison in what is now southern Arizona, and the foundation for the Village of Tubac.

It is built to protect the Spanish missions colonists who have settled, since the 1730s, in the area of Tubac, a small Pima Indian village. One year after a Pima uprising destroyed the Spanish settlements, the Pimas surrender and the fort is build to prevent further rebellion. Tubac becomes the first European settlement in what is now the state of Arizona. Tubac also becomes one of the key stops on the Camino Real (the Spanish colonial trail) from Mexico to the Spanish settlements in California and the site of many battles from the Apache-Mexico Wars to the American Civil War. Today, the Tubac Presidio State Historic Park, adjoining the Village of Tubac, preserves the Presidio's ruins. The park features several historic sites, a museum, and an underground archeology exhibit displaying the excavated foundations of the Tubac Presidio. It also features living history presentations, on Sundays from October through March. The park also marks the Trailhead of the Juan Buatista de Anza 1774 expedition from southern Arizona to northern California. Although it is Arizona's first state park, and the word "state" still is part of its name, due to budget cutbacks, the park is no longer operated by the Arizona parks system. In fact, the park would have been closed in 2010, had it not been saved by dedicated volunteers, The Friends of the Presidio, who now operate the facility. By Venus McGee Ramirez, Lehman College |

|

|

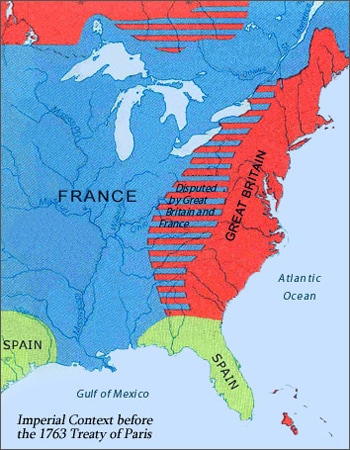

Spain trades Florida to England in exchange for Cuba. As a result of the Seven Years (French-Indian) War, in which Great Britain defeated France and Spain, England gets all French territory east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans. And Spain gives up East and West Florida to the British in return for Cuba, which Spain had lost during Seven Years War.

This is all the result of the Treaty of Paris of 1763, which ends the long, bloody war and sets the Florida peninsula on a totally different course. More than two decades after the Spanish government in Florida had granted unconditional freedom to all runaway slaves from the British plantations in South Carolina, Britain imports thousands of new slaves from Africa, and from other British colonies, to Florida. Yet, because England had gone into debt to fight the Seven Year War, and because it was forced to imposed heavy taxes on its North American colonies, the Treaty of Paris May have triggered the American Revolutionary War against Britain a few years later. Twenty years later, it took another Treaty of Paris -- in 1783 -- to return Florida to Spain. This second Treaty of Paris brings an end to the American Revolution, after the Americans colonies defeated the British with the help of Spain. By Justin Acosta, Lehman College |

|

|

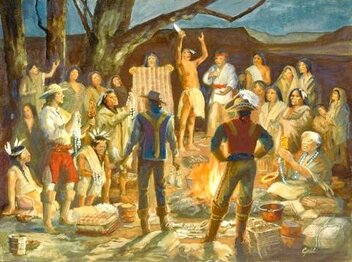

Spanish military officer and first governor of Las Californias, Gaspar de Portolà leads the first overland expedition from Baja California to Alta California, visiting many of its most important landmarks from San Diego to San Francisco Bay, and taking with him the soldiers and Franciscan friars who establish the first California Spanish forts and Franciscan missions.

Traveling with Portola is Father Junípero Serra and other Spanish Franciscan missionary priests with the quest of bringing Christianity to the Natives of California. His quest, following orders from Spain, is to prevent English and Russian encroachment into territory that is already claimed by Spain. They establish settlements (now cities) at San Diego Bay and Monterey Bay, at landmarks discovered by sea some 227 years earlier -- by Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542, and revisited by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602. The expedition has a sea component. After weathering storms, two ships catch up with the land detachment at San Diego Bay. After leaving a contingency in San Diego, including Serra, the expedition keeps marching north, finds another bay, but fails to identify it as the one described by Vizcaino. And so, they keep marching, until they discover San Francisco Bay, which had not been discovered by sea! After returning to San Diego, Portolá organizes a second land expedition – followed by Serra on a ship – and finally identifies Monterey Bay, where they built another Spanish fort, and another Franciscan mission. Along the way the Portolá expedition discovers and names many other California landmarks, including el “Rio De Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciuncula,” known today as the Los Angeles River, and from where the City of Los Angeles got its name. |

|

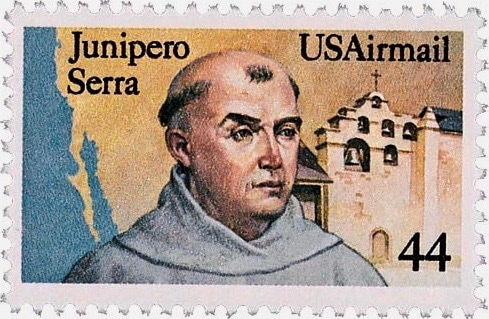

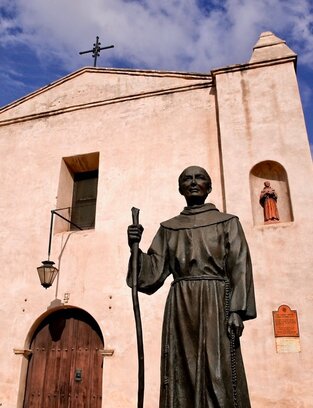

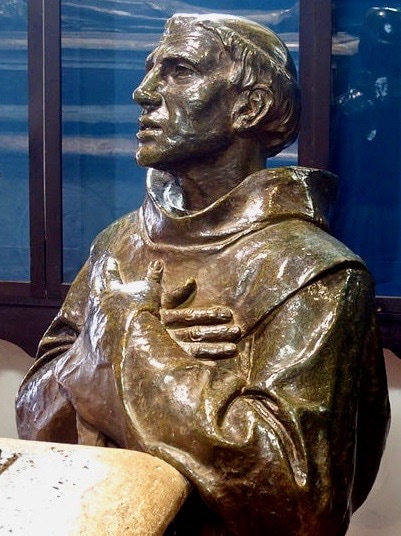

Father Junipero Serra, a Franciscan priest, arrives in California, from Baja California, as part of the Gaspar de Portolá overland expedition and establishes the San Diego De Alcalá Mission, the first of 21 Spanish missions built along the coast of California to convert the natives to Christianity - and the foundation for today's City of San Diego.

Known as the "Mother of all missions," San Diego De Alcalá marks the beginning of Catholicism in this region, and the gateway that opened California to Spanish and Mexican settlement. Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo had claimed California for the Spanish empire in 1542, but they did not settle in the area until Father Serra leads a groups of Franciscan priests who establish the first nine of California's 21 missions. With a reliable source of water, fertile land, and the proximity to a Native American village, Father Serra choses the site of the mission, overlooking the Bay known today as Presidio Hill, to cultivate crops such as wheat, barley, corn, and beans. Today Father Serra is remembered for his dedication to his faith, and for bringing Catholicism to California. To recognize his dedication, Pope Francis canonized Father Serra during his first visit for the United States in 2015, at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. There is a bronze statue of Serra in the Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol. Throughout California, his work is recognized with statues -- in Ventura, Hillsborough, San Juan capistrano, Fremont, and Monterey. There is even a Junipero Serra Museum in Presidio Park, California. It showcases San Diego's cultural influences from the indigenous Kumeyaay to the Spanish, Mexican and early American settlers. By Jungmin Park, Lehman College |

|

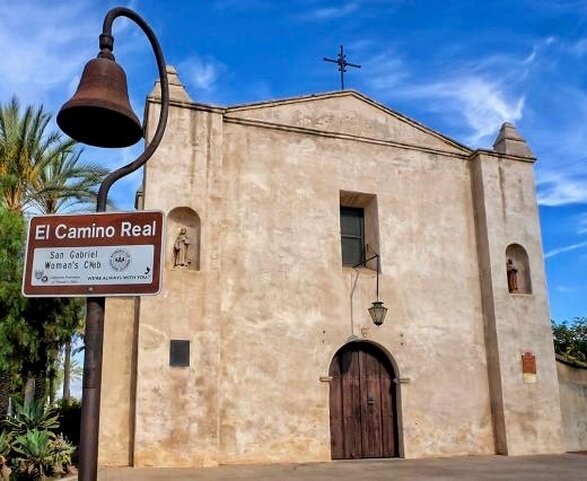

Father Junípero Serra, Roman Catholic Spanish priest and leader of Franciscan missionaries on the Gaspar de Portola expedition, establishes the San Gabriel Arcángel mission in present-day Los Angeles County, California to convert Native Americans to Catholicism. It is the fourth of 21 missions eventually built in California and the foundation for the City of San Gabriel.

Originally planned to be built along the Santa Ana River, Serra changes the location to the slopes of Montebello, overlooking the San Gabriel Valley because of its fertile plain. Yet, the original mission is destroyed by a flood and is moved three miles northwest to where it stands today. The mission grew into a city, which although incorporated in 1913, had been the original township of Los Angeles County since 1852. Although San Gabriel's motto is "A City with a Mission," it is also known as "The Birthplace of Los Angeles," since the pioneer Los Angeles settlers first gathered at San Gabriel mission before setting out to build "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Angeles" in 1781. The march of the first Los Angeles pobladores, from the mission to downtown Los Angeles -- “Los Pobladores Historic Walk to Los Angeles” -- is still celebrated every year during labor day weekend. The mission still serves as an active Roman Catholic Church. The mission grounds, cemetery, museum and gift shop are open to visitors daily. By Chadae McAnuff, Lehman College |

|

Based on the success of a hunting expedition – more than 25 mule loads of dried bear meat – Father Junípero Serra selects the site to establish Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, the fifth of the 21 California Spanish missions and the namesake of today’s City of San Luis Obispo.

Facing a food shortage while based at Misión San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (also known as Mission Carmel in today’s City of Carmel-by-the-Sea), Serra remembers the stories he has heard from the soldiers in the Gaspar de Portola expedition, stories of a valley with plenty of bears and buffalo. In fact, the soldiers already have a name for that area. They call it “El llano de los osos” – “The Valley of the Bears.” Serra has been told that this area has a mild climate, with plenty of food and water, and that the local Chumash natives are very friendly. And so he decides to send a hunting expedition down south to The Valley of the Bears. The expedition is so successful that, instead of continuing to send other hunting parties to that area, Serra decides to build the fifth California mission there. He leads a small group down to El Valle de los Osos, carrying some mission supplies, and establishes Misión San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, named after Saint Louis of Anjou, the bishop of Toulouse. He celebrates the first Mass there. But the construction of the mission is then left to father Jose Cavaller, along with five soldiers and two neophytes. Although the mission population grows, in 1776, four years after its establishment, Native Americans who resist the mission way of life, burn down the mission. And they do it two more times, until Cavaller decides to replace the original buildings, and their wooden-stake walls, with adobe and tile structures. After 1810, when Mexico begins its war of independence from Spain, like the other California Spanish missions, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa faces a decrease of funds and supplies from Spain. And after 1821, when Mexico wins its independence and secularizes the missions, Spanish friars are replaced with Mexican missionaries and management of the missions is turned over to government administrators. Mission lands often are sold and divided into “ranchos.” Mexican Governor Pio Pico sells Misión San Luis Obispo – everything but the church – for $510.00 in 1845. Mission buildings go on to be used a school, a jail and the first county courthouse. After California becomes part of the United States in 1848, and a state in 1850, the Catholic church petitions the U.S. government to return some of the Mission properties back to the church. These mission buildings have undergone considerable structural alterations over the years, and although they were somewhat different than the originals, in the 1930s, they undergo extensive restoration to transform them back to the architectural style of the early Spanish missions. Misión San Luis Obispo has a secondary nave, situated on the right side of the altar, forming the only L-shaped mission church in California. It is also the only mission where the bells have names: Sorrowful, Joyful, and Gloria. Nowadays, still in the center of downtown, in the City of San Luis Obispo, the mission features gardens, a museum, a gift shop and a Roman Catholic Parish. By Maria Fernandez, Lehman College |

|

|

Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón, the foundation for the City of Tucson, Ariz., is established by Spanish army soldiers led by Captain Hugh O’ Connor, an Irish mercenary working for Spain, also known as El Capitan Colorado (The Red Captain).

Seeking to gain greater control of Arizona and strengthen New Spain's northern border, O'Connor decides to move the Spanish fort at Tubac, Ariz., built 23 years earlier, almost 50 miles north, to an area surrounded by mountain ranges, the site of present-day Tucson. But the original Tucson fort is poorly constructed, and, after an Apache assault in 1783, its palisade (wooden stakes) fence is replaced by an 8 to 12-foot-high a mud-brick wall that is about 700 feet long on each side -- making the Tucson Presidio one of the strongest and largest frontier forts. After the Americans arrive in 1856, the original walls are demolished, with the last section torn down in 1918. But almost a century later, following an archaeological excavation that located the fort's northeast tower, the northeast corner of the fort is rebuilt in downtown Tucson in 2007. It is now a museum paying tribute to Arizona's Spanish history, at 196 N Court Ave, Tucson, AZ. It is open Wednesday thru Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $5 for adults and $1 for children. They offer guided tours and "Living History Days" with Volunteer re-enactors of life at the fort in the late 1700s. Museum visitors can see the small living quarters of a military family, the barracks where some soldiers stayed, the ammunitions room, and the presidio warehouse where food and other commodities were kept. Visitors can an enjoy Spanish colonial food, listen to the stories of early Tucsonans and get a glimpse into the lives of Spanish-Americans in the 18th century. By Dahianna Feliciano, Lehman College |

|

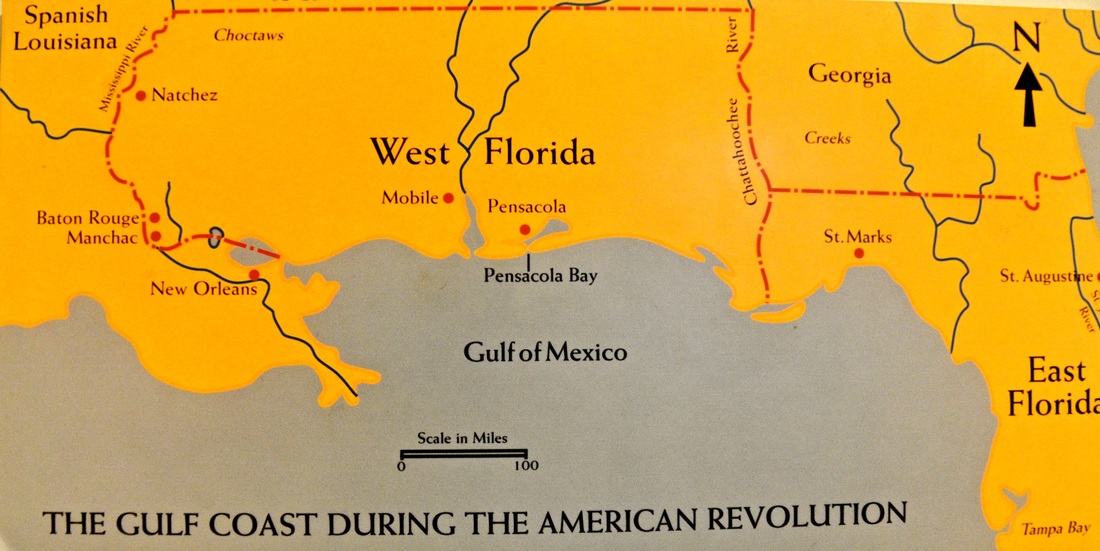

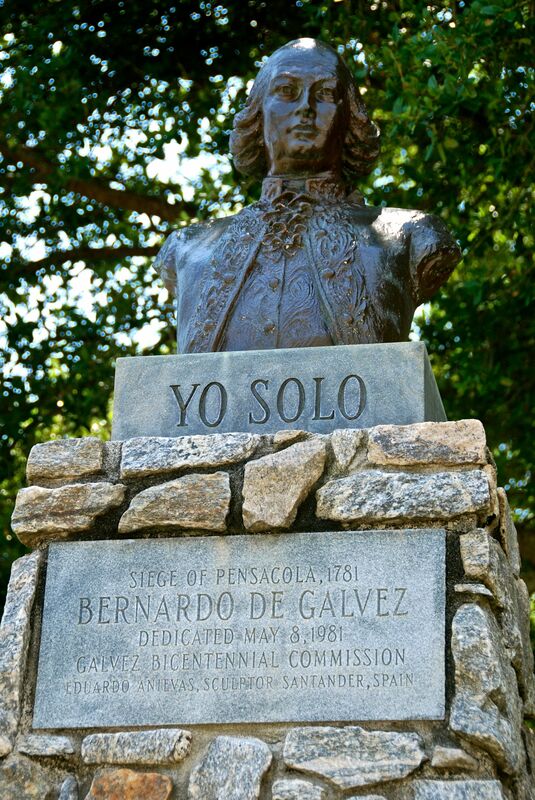

1776-83Hispanics in the American RevolutionSpain deems the American army a viable ally after troops led by General George Washington capture the Hessian (German) Garrison, in the Battle of Trenton, New Jersey. Spain’s agreement to work in support of the Continental Army – although covertly – formally establishes the Hispanic participation in the most important war in American history: The American Revolution.

The Hessians are German mercenaries hired to fight for the British. This small victory, in an array of losses for General Washington, encourages more American colonists to enlist and prompts Spain’s King Carlos III to covertly begin supporting Washington and his troops. Spain secretly sends supplies to American ports, aiding the colonists by smuggling material from Cuba and other Caribbean islands. King Carlos III encourages his American subjects to donate pesos to fund the cost of the war. Yet, Spain’s support of a colonial rebellion against a monarchy remains mostly undercover, to prevent a riotous rebellion in their own nation. But that’s until – with King Carlos III’s blessing – Don Bernardo de Galvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, enters Spain into the fight of the 13 colonies, blatantly declaring Hispanic participation in the American army. Galvez leads an army of thousands of Hispanic soldiers – mostly from Mexico and the Caribbean Spanish colonies – across the Gulf of Mexico, defeating the British in Natchez, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama and Pensacola, Florida. The success of his military operations, in effect, cover Washington’s rear (southwest) flank, allowing the Continental Army to concentrate on fighting the British along the eastern front. Galvez’s successful military operation along the Gulf of Mexico opens up a supply channel along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers by which Spain can send weapons, gunpowder, military uniforms, and even cattle to Washington’s troops – while avoiding British interference. Spain’s aid, and Galvez’s heroic success, were a surprise to the British, and huge factors that affected the outcome of the American Revolution. Galvez’ conduct during that pivotal time in American and Hispanic history has not gone unnoticed. In 2014, a joint resolution of the U.S. Congress, signed by President Barack Obama, made Galvez an Honorary Citizen of the United States, the seventh person to receive this high honor! By Deseree Velasquez, Lehman College |

|

|

Spanish Army Lieutenant José Joaquin Moraga and Francisican missionary Francisco Palóu reach San Francisco Bay as part of the 1,000-mile Juan Bautista de Anza overland expedition from present-day southern Arizona and establish Mision San Francisco de Asis, also known as Mision Dolores -- the foundation of what is to become the City of San Francisco.

While the 13 American colonies on the east of North America are declaring their independence from Great Britain, on the west coast, Father Palóu dedicates the site and celebrates the mission's first mass on June 29, 1776 -- only a few days before the American Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence. The mission, of wood poles plastered with mud and thatched roofs, is formally founded with a great celebration on Oct. 9, 1776. At a nearby site designated by De Anza, three months earlier, Moraga also leads the construction of the Presidio of San Francisco, formally established on September 17, 1776. Mission San Francisco is the sixth of 21 Spanish missions to be established in California by Franciscan missionaries, to convert the native people to Christianity, colonize the area and to consolidate Spanish power. But, like many other missions, this mission is not just a religious institution; it quickly becomes the gathering center for soldiers, farmers, traders, and native peoples, with a significant number of Indian converts who become resident community members and perform all of the tasks necessary to keep the community running. Both the mission and the presidio are named after Saint Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan Order in Italy, and already the namesake of San Francisco Bay. The name San Francisco de Asis was first given to a small bay (now Drake Bay) by Spanish explorer Sebastián Cermeño and was later applied to the bay. Today, Mission Dolores, recognized as a California Historical Landmark, is the oldest surviving structure in San Francisco. The old mission chapel is part of a much larger structure dedicated in 1918 and granted Basilica status in 1952. The Presidio of San Francisco, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962, is now a park on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula, part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. By Sirky Sanchez, Lehman College |

|

|

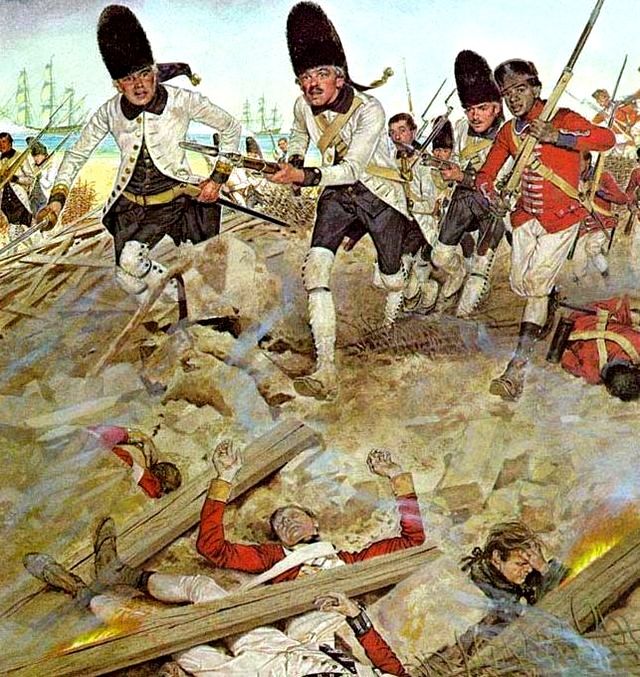

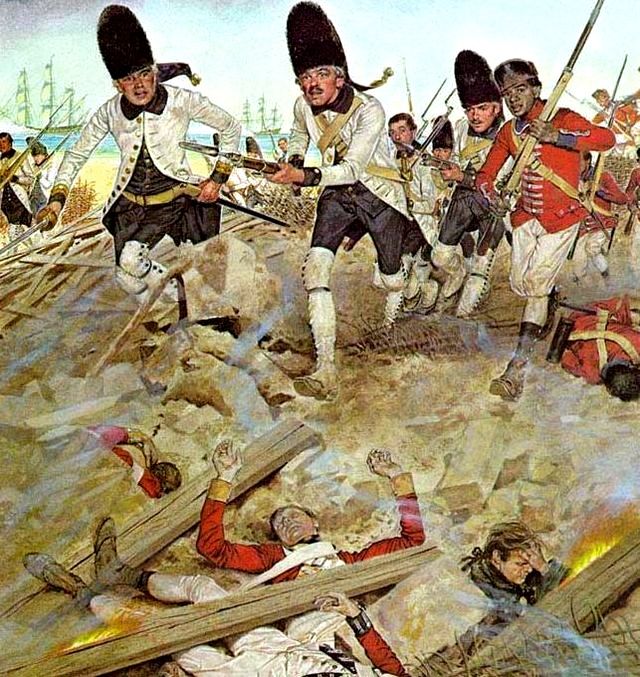

Field Marshal Bernado de Gálvez y Madrid, Governor of Louisiana and commander of Spanish forces in North America, leads a successful two-month siege and subsequent capture of Pensacola, Florida, during the American Revolutionary War.

After Spain formally declares war against the British on June 21, 1779, in support of independence for the 13 American colonies, Gálvez and his Spanish soldiers, including many Latin American recruits, cut a path of victories along British held territory along the coast of Gulf of Mexico, culminating in the capture of Pensacola on May 10, 1781. The victory turns the tide of the American Revolution! With Pensacola and the Gulf Coast under Spanish control, the British cannot effectively attack George Washington’s troops from the rear, allowing Washington to focus his resources on the war’s eastern front. Before reaching Pensacola, leading a force for 40 ships and 3,500 men, Galvez defeats the British at Mobile Bay and takes control of Fort Charlotte. When he reaches Pensacola, Galvez commands a siege of the main British fort defending the city, Fort George – but not without considerable losses. As Spanish soldiers build trenches surrounding the fort, they are constantly harried by pro-British Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw Indian raiding parties. It is not until the second month of the siege, when 1,600 reinforcement troops arrive from Havana, that the tide begins to turn against the British. Now Galvez leads some 7,800 men against some 2,000 British soldiers in Pensacola. The siege is defined by extensive battery fire, and trench warfare, causing heavy loses on both sides, and the ultimate surrender of all British forces in Pensacola. British General John Campbell, no longer able to withstand unforgiving Spanish artillery, raises the white flag of surrender on May 8, and Pensacola officially comes under Spanish control on May 10, 1781. The surrender of Pensacola places the entire province of West Florida under Spanish control. Pensacola remains under Spanish control for the next 40 years. By Jonathan Yubi-Gomez, Lehman College |

|

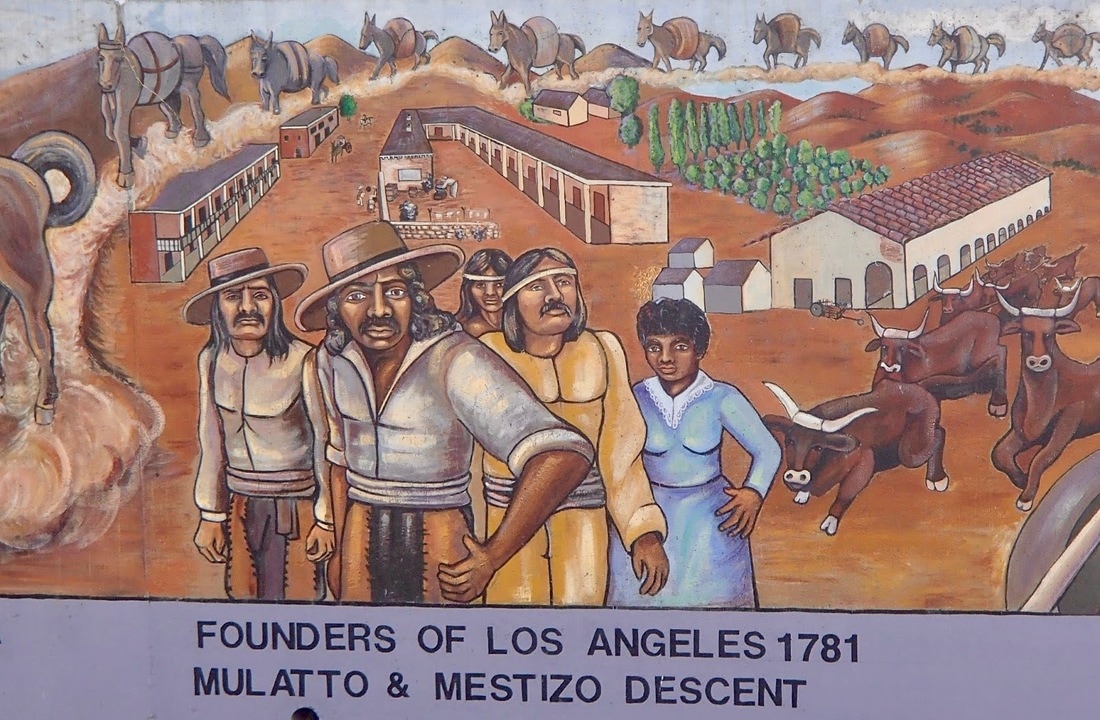

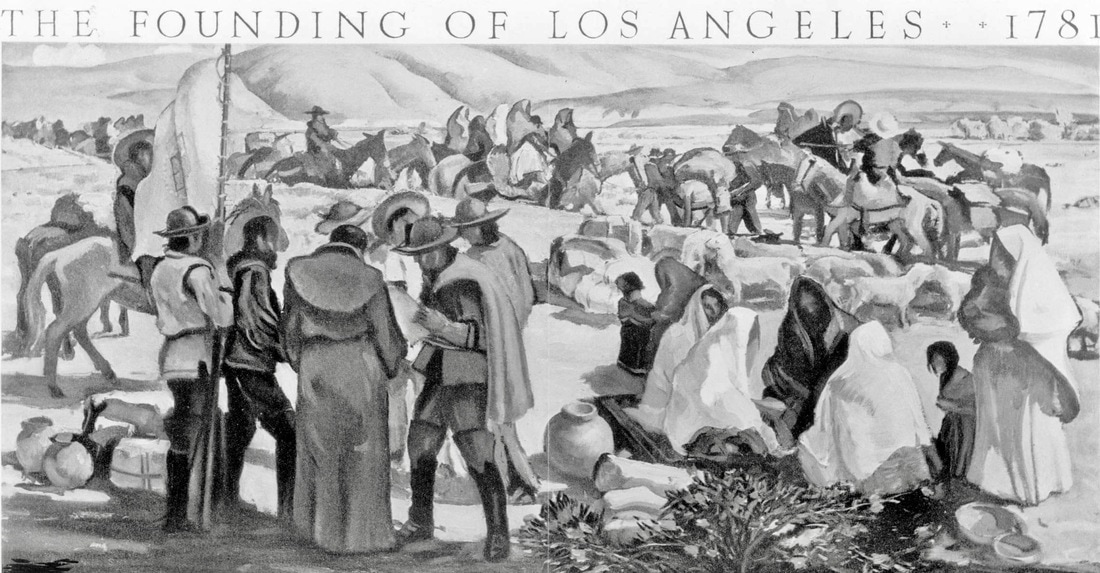

A group of about a dozen families are recruited Spanish authorities in Sinaloa, Mexico, to make a long journey to Alta California and establish El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Angeles (The Town of Our Lady, the Queen of the Angels), now known as Los Angeles.

The 44 settlers – 22 adults and 22 children – had first gathered at San Gabriel Mission, established 10 years earlier, from where they set out looking for the right site for the new town. Escorted by a military detachment and two priests from the mission, they settle in what in now downtown Los Angeles. The "Pobladores" of Los Angeles, mostly farmers, rapidly establish a successful community. The streets of downtown Los Angeles still follow the same pattern of the streets of the old colonial town. The old town limits are still marked by Hoover and Indiana Streets in the west and east respectively. Today, Los Angeles embraces and recognizes its beginning by celebrating the annual "Los Pobladores Historic Walk to Los Angeles." It happens over the Labor Day weekend and coincides with the anniversary of the city's founding. It is organized by Los Pobladores (Townspeople) 200, an association of the descendants of the original 44 settlers and soldiers who accompanied them. The walk starts from the San Gabriel Mission to El Pueblo de Los Angeles, and follows the historic route that was taken by Los Pobladores. By Dionaly Carrasco, Lehman College |

|

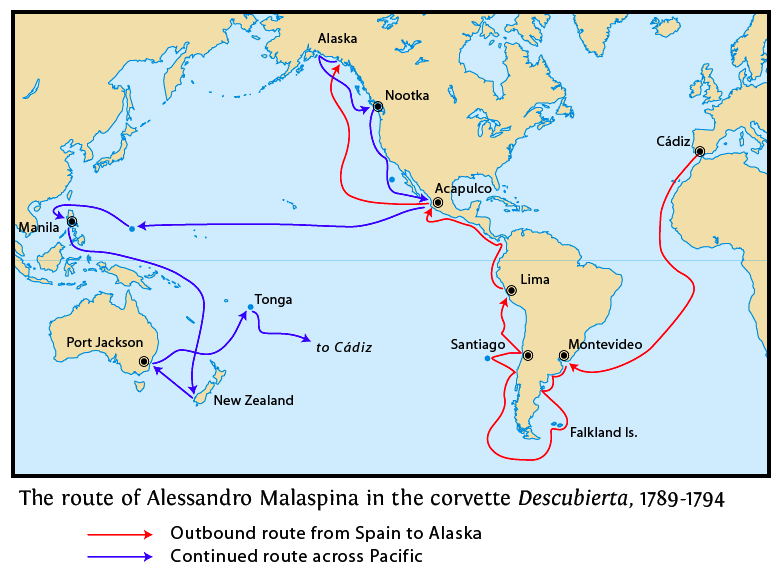

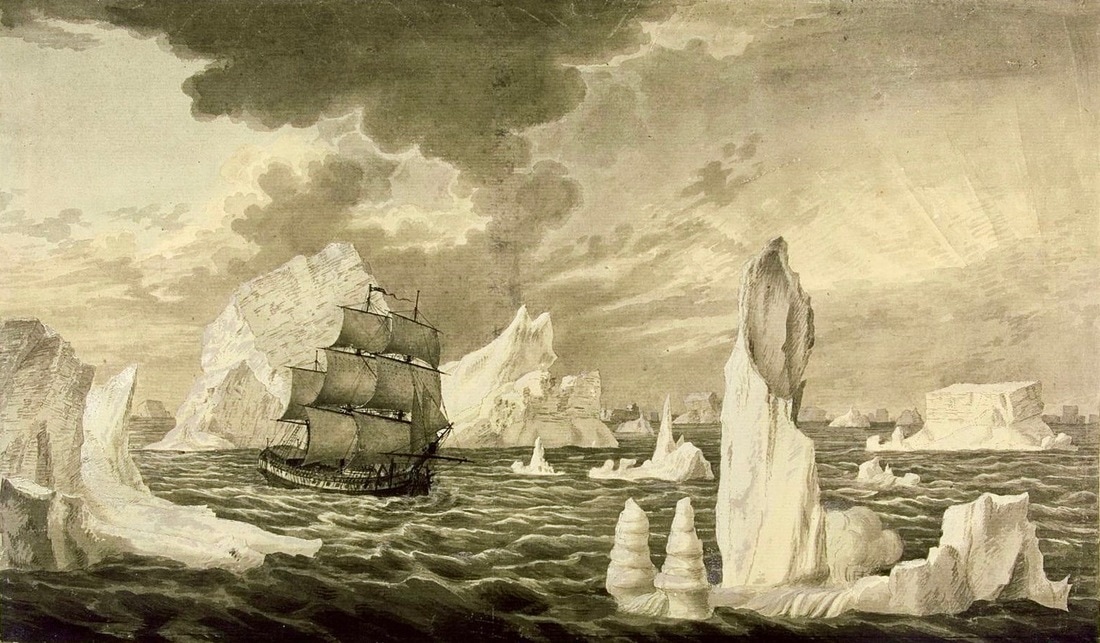

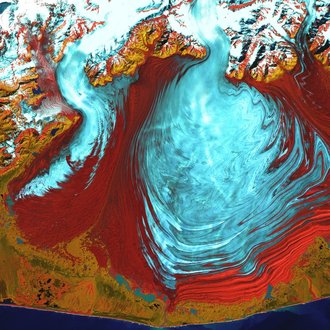

Alessandro Malaspina an Italian-born Spanish naval officer leads a two-ship scientific expedition from Cadiz, Spain across the Atlantic Ocean, around Cape Horn and all the way up the West coast of the Americas to the Gulf of Alaska.

Although he expects to sail from Mexico across the Pacific Ocean, by the time he gets to Mexico, Malaspina receives orders from the King of Spain to continue northward along the Pacific Coast of North America in search of the Northwest Passage, that long-sought waterway that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Sharing command of the voyage with another Spanish naval officer, José de Bustamante y Guerra, the Malaspina expedition sails from Acapulco, Mexico directly to Yakutat Bay, Alaska. Although they supposedly share "dual command," even de Bustamante acknowledges that Malaspina is the chief the expedition. They never find the illusive Northwest Passage, but the expedition and its Spanish scientists spend a month studying the lifestyle of the Tinglit, the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Spanish scholars study and document the Tinglit's language, customs, economy, warfare methods and even burial practices. Spanish artists paint portraits of the tribal members and sketch scenes of Tinglit daily life. Spanish botanists collect many new plants. They also surveyed the Alaska coastline, measured the height of Mount Saint Elias and explored huge glaciers, including the Malaspina Glacier, subsequently named after him. Aside from the Malaspina Glacier in southeastern Alaska, which is the world's largest piedmont glacier, there is also a Mt. Malaspina and a Malaspina Lake in Alaska, and a Malaspina Strait, a Malaspina Village and Malaspina Provincial Park in Canada. By Karen Anderson, Lehman College |

|

Franciscan missionary Fermín Francisco de Lasuén establishes Misión San Fernando Rey de España in present-day Mission Hills, Los Angeles County, California. It is the 17th of 21 Spanish missions to be established in California to convert the native people to Christianity, colonize the area and to consolidate Spanish power. It is also the fourth mission established by de Lasuén in as many months.

Named for Ferdinand III, King of Spain (1217-1252), the mission becomes the namesake for the nearby City of San Fernando and the San Fernando Valley. After the death of Father Junípero Serra in 1784, Father de Lasuén was appointed the second Presidente of the missions of California in 1785, and has continued the missionary work begun by Father Serra -- establishing settlements where Spanish settlers and Native Americans can coexist in harmony. But life is tough for the first few years after these missions get started. Spanish settlers and Native Americans initially depend on supplies delivered by sea from New Spain. It normally takes a few years before they can plant sufficient crops and raise enough cattle to become self-sufficient. But sometimes the supples are hard to come-by. And because both the settlers and the natives have an urgency to survive, there is always a rush to train the natives on European-style farming. The quadrangle-shaped mission is built with adobe bricks by the Tongva natives of the region. The mission's convento (main building) took 13 years to build and was completed in 1822, becoming the largest two-story adobe mission building in California. Today, the convento remains as the only original building at this mission, which serves as a museum and as the Archival Center for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. The mission church is an active Roman Catholic Church. By Michelle Acosta, Lehman College |

|

|

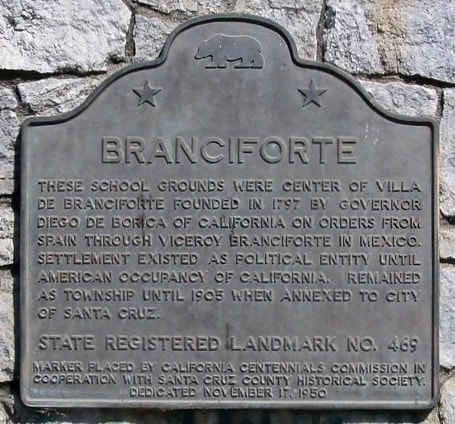

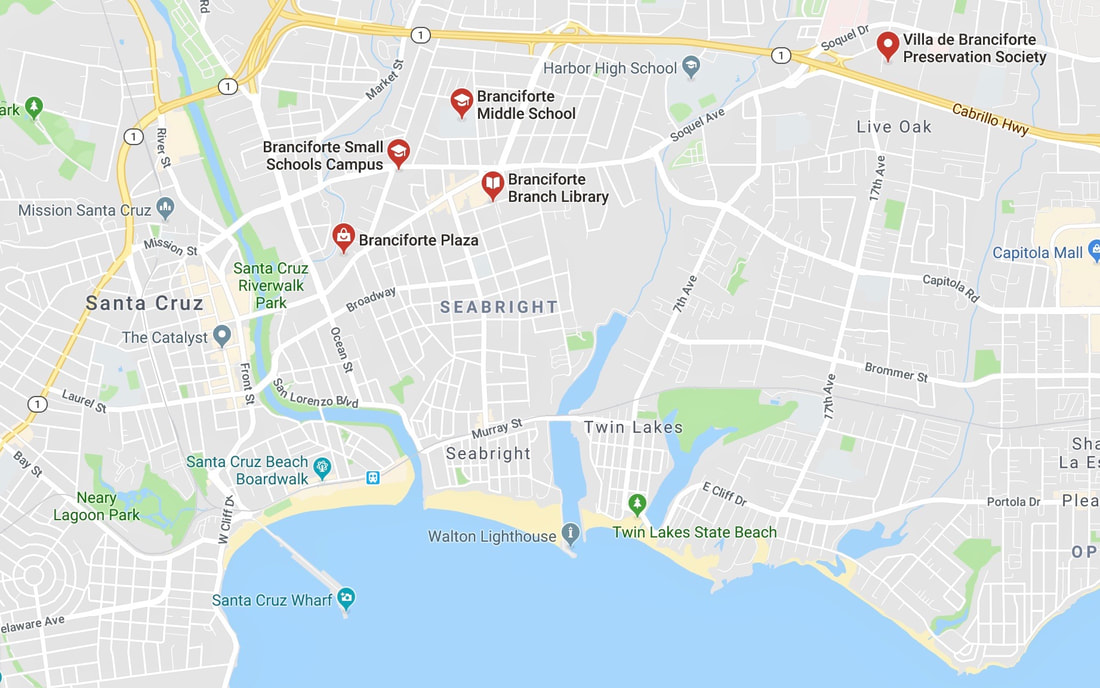

Eight settlers from Guadalajara, New Spain, make an arduous journey to Alta California and are the first to establish a village that is to be called Villa de Branciforte.

The new town – now part of the City of Santa Cruz, California – is built on a bluff, facing Mission San Cruz, founded six year earlier on the other side of the San Lorenzo River. It is the result of Spain’s effort to protect its territories and influence in the New World. To prevent France, Russia and England from encroaching on Spanish territories, Spain decides that more towns need to be built and Alta California has to be populated by Spanish subjects. Following orders from the Spanish crown, New Spain’s Viceroy, Don Miguel de la Grúa Talamaca de Carini y Branciforte, orders the establishment of the new town. However, knowing that he would have to send new settlers to live in Alta California, and that it would be costly and difficult to populate the town, Viceroy Branciforte recruits residents of Guadalajara, by promising them money, land and the best adobe houses available. But when the first settlers arrive at the new village, they find that they have been mislead. The land is bare, abandoned, and has to be worked. The Viceroy’s promises never materialize. However, since trekking all the way back to Guadalajara is not a viable option, the settlers decide to make due with their limited tools and resources. They build a village without much help from Spain. Branciforte, an Italian military officer of Spanish nationality, serves as the 53rd Viceroy of New Spain, from 1794 to 1798, but never travels north to see the town. He is remembered by history as a very corrupt administrator. Nevertheless, although he has misled its colonists, Villa de Branciforte is named after him by Spanish California Governor Diego de Borica, who has overseen the creation on the village. Unlike other Alta California Spanish settlements, especially Los Angeles and San Jose, the settlers of Villa de Branciforte receive little support from the Spanish crown, or the Catholic missions. While the Crown helps to support active Spanish soldiers and Franciscan missionaries, in forts and missions, the Villa Branciforte colonist are merchants, explorers and retired soldiers. And unlike other settlements and forts which receive some support from nearby missions, Villa de Branciforte gets little help from Misión Santa Cruz, on the west side of the San Lorenzo River, where the Franciscans see the new village as a threat. They fear that Native Americans living at the mission will be negatively influenced by the town’s decadence. But the people of Branciforte, determined to overcome these obstacles, as if defying the Spanish Crown’s neglect, develop a sense of belonging for their new hometown. In 1802, five years after its inception, the village’s total population is 107. And yet the settlers create a civil government and, in 1803, elect Jose Vicente Mojica as the first mayor of Villa de Branciforte. This is one of the first times elections are held in Alta California. When Mexico wins independence from Spain in 1821, and Alta California becomes part of Mexico; and again in 1848, when California becomes part of the United States, dramatic instability and changes affect the village. Villa de Branciforte becomes an American town. It functions as a township until 1905, when the village is annexed to the City of Santa Cruz. Nowadays, Villa de Branciforte is known as East Santa Cruz. The Branciforte Small Schools Campus building now stands at was the center of Villa de Branciforte. But traces of the Villa still exist there. There is a creek, an avenue, a library, two schools, and an 18th century adobe house named Branciforte. There is a Branciforte Fire District. There is a Villa Branciforte Preservation Society seeking “recognition and preservation of the unique character and history of the Villa de Branciforte area,” according to its website. “This includes the preservation of historical landmarks, the "living history" and diversity of our local architecture with roots in the adobes of the Spanish Colonial period, and significant archaeological features, such as adobe foundations, adobe bricks, roof tiles, burial sites and other archaeological finds pertaining to the early inhabitants of Villa de Branciforte.” By Miguel Monsalvo, Lehman College |

To enlarge images, click on them!

|

Go to: 16th Century 17th Century

What's Missing? Que Falta?

Please note that this timeline is devoted to the Hispanic presence in North America starting on April 2, 1513. While Latin America Timelines obviously begin much earlier, and cover the history of our antecedents in Latin America and Spain, they often exclude everything that happened in North America - even the accomplishments of the conquistadores who came north from the Caribbean and Mexico, and the Hispanics who followed them! With our timeline, our goal is to fill the huge gaps that leave U.S. Hispanics out of U.S. history.

|

Help us build this timeline! Click:

https://www.facebook.com/HiddenHispanicHeritage And tell us: Which major historical event are we missing? |

´Ayúdenos a construir esta cronología! Clic:

https://www.facebook.com/HiddenHispanicHeritage Y díganos: Qué gran evento histórico nos estamos perdiendo? |

|

Are you on Twitter? For Updates on HiddenHispanicHeritage.com

Please follow me: @ColumnistPerez https://twitter.com/ColumnistPerez |

|