77. When Gálvez Came to Congress

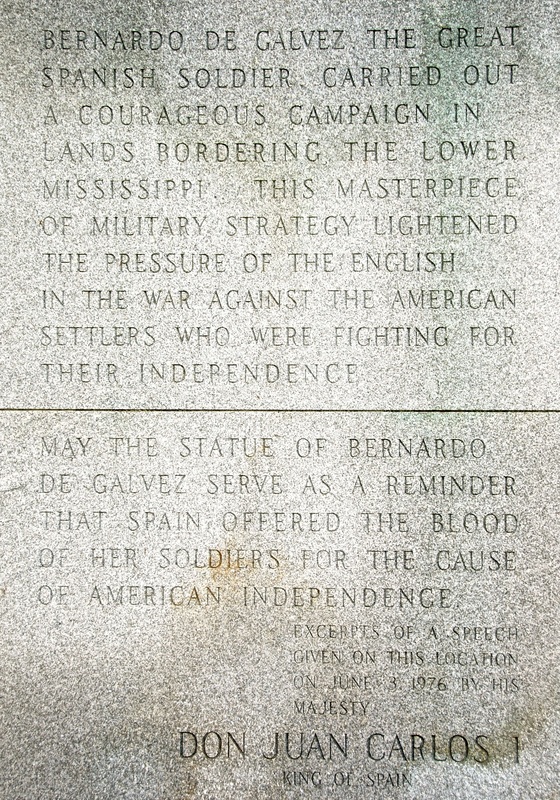

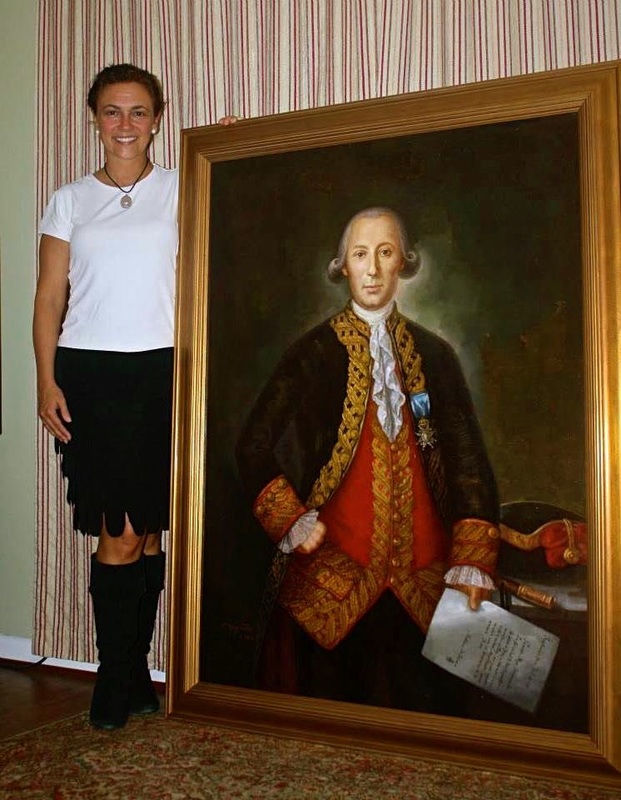

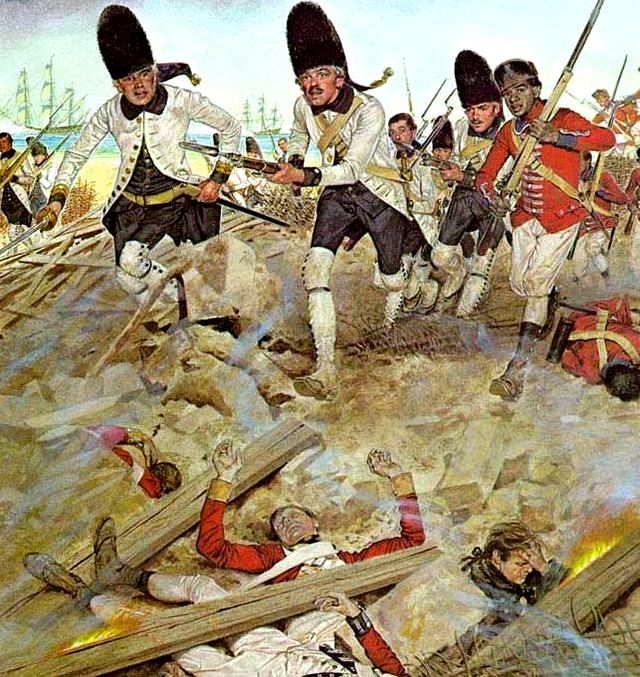

|

By Miguel Pérez

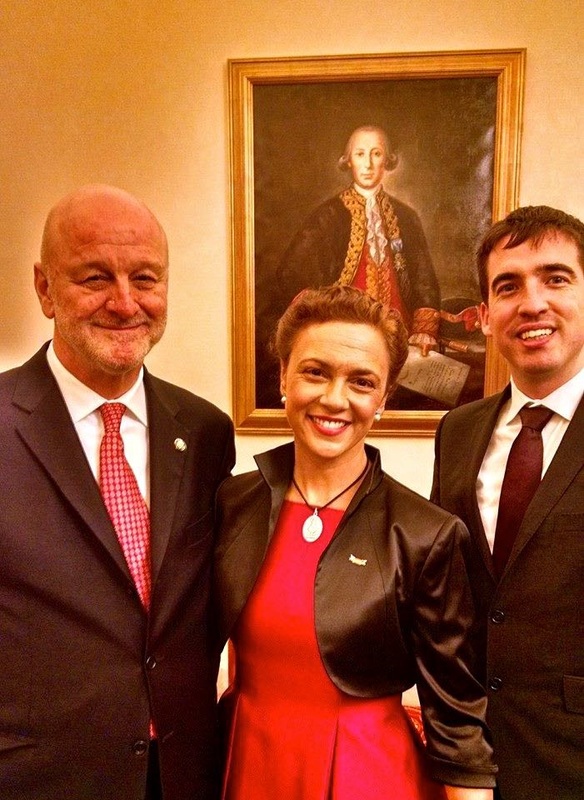

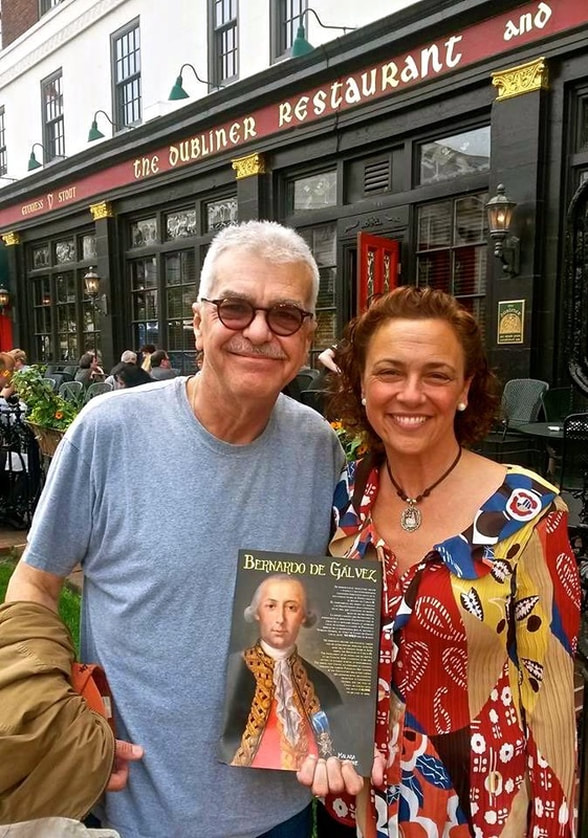

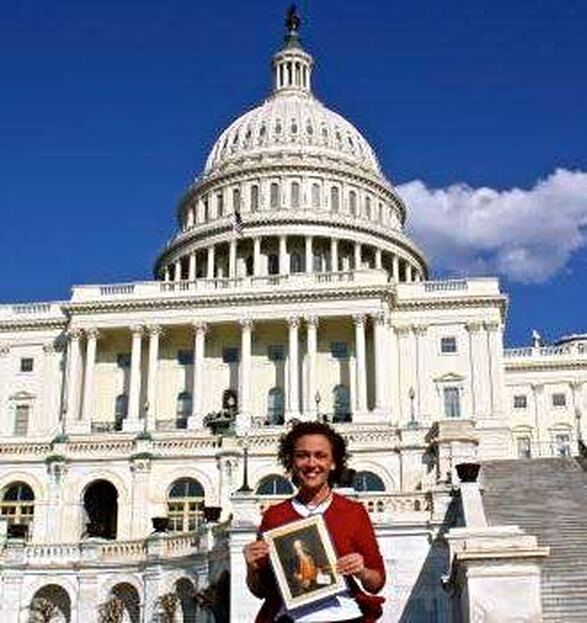

WASHINGTON — February 2, 2015 - It took Congress 231 years to keep this particular promise, perhaps setting a record, but it finally happened in December, when a portrait of Spanish Gen. Bernardo de Galvez finally was hung on a wall in the U.S. Capitol. Back on May 9, 1783, the Continental Congress resolved to display a work of art that would honor Galvez's service to the United States during the American Revolution. As the governor of Spanish Louisiana, Galvez had supplied food and ammunition for George Washington's troops and had led Spanish and Latin American forces to defeat the British all along the Gulf Coast. His support of the Colonies and his contributions to American independence from Britain were so crucial that the Continental Congress wanted to display its gratitude. But somehow, it didn't happen. For more than two centuries, no one took the initiative to fulfill that promise — at least not until Teresa Valcarce read about it in an article she received from Spain. Valcarce, a Spanish-born secretary in Washington, read the article as if she had been given a mission. She went on a yearlong one-woman crusade to lobby Congress to keep its unfulfilled promise. She searched through congressional records, contacted scholars and diplomats in Washington and Spain, enlisted a representative and a senator to champion her cause, found a Spanish cultural organization that would support the project, and recruited an artist who would paint the portrait — free of charge. And then she demonstrated her self-proclaimed "nagging abilities" until she got what she wanted. "I was determined to see that the promise of our Founding Fathers was fulfilled," said Valcarce, who is an American citizen and Maryland resident. She got Spanish artist Carlos Monserrate to paint an exact copy of a 1784 portrait of Galvez, which was commissioned by the Spanish crown. And she persuaded Rep. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., and Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., to seek a place to hang the painting and authorization to do it. She became so persistent that in the halls of Congress, she became known as "The Portrait Lady." Her quixotic quest was accomplished Dec. 9, 2014, when Menendez, Spanish Ambassador Ramon Gil-Casares and many other dignitaries joined her in a portrait hanging ceremony in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee room — S-116 — where Galvez's image will oversee the proceedings from now on. "Sometimes things that are really important require a lot of persistence and a lot of nagging to see them through," Valcarce said. "Nowadays we see how hard it is to get anything accomplished in Congress," she added jokingly. "But 231 years? Really?" Her speech is available on YouTube. The clip is titled "Teresa Valcarce - Bernardo de Galvez portrait's ceremony." 2014 was definitely Galvez's best posthumous year. Washington, D.C., already had an impressive bronze equestrian statue of the Spanish general — on Virginia Avenue near the State Department. But this was the year when Galvez finally came to Congress! Last summer, as my Great Hispanic American History Tour headed west and visited many of the Gulf Coast sites where Galvez scored major victories against the British, back in Washington, Galvez's name echoed in the halls of Congress. In July, while I was writing about Galvez from Pensacola, Florida, Mobile, Alabama, and the town named after him, Galveston, Texas, in a column titled "The Hispanic Flank of the American Revolution," the House of Representatives was passing a bipartisan resolution to grant him honorary U.S. citizenship posthumously. As I read the news about the citizenship legislation, I wanted to divert the tour and head back east just to cover the Galvez story. This is an honor that only has been bestowed on seven other people, including Winston Churchill and Mother Teresa. How often do we see U.S. Hispanic historical figures getting this kind of recognition? The resolution noted that Galvez "was a hero of the Revolutionary War who risked his life for the freedom of the United States people and provided supplies, intelligence, and strong military support to the war effort." It also noted that: • "His troops seized the Port of New Orleans and successfully defeated the British at battles in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Natchez, Mississippi, and Mobile, Alabama." • He "led the successful 2-month Siege of Pensacola, Florida, where his troops captured the capital of British West Florida and left the British with no naval bases in the Gulf of Mexico." • Having been wounded in Pensacola, Galvez demonstrated "bravery that forever endeared him to the United States soldiers." • His victories "were recognized by George Washington as a deciding factor in the outcome of the Revolutionary War." • He "helped draft the terms of treaty that ended the Revolutionary War." • He "helped secure the independence of the United States." Two other foreign-born heroes of the American Revolution — Frenchman Marquis de Lafayette and Polish military officer Casimir Pulaski — already were among the seven who had been made honorary citizens. But somehow a Hispanic hero of at least equal importance had not yet been recognized. The joint resolution making Galvez the eighth honorary American citizen, sponsored by Rep. Jeff Miller and Sen. Marco Rubio, both Republicans from Florida, was introduced in January 2014 and passed by the House in July. But the Democratic-controlled Senate didn't approve it until Dec. 4, five days before Galvez's portrait was hung in Congress. President Barack Obama signed it, among several other bills, Dec. 16 as he was rushing off to Hawaii for the holidays, and unfortunately, Galvez's citizenship — when it finally became official — didn't get much press, certainly not so much as it did when it was passed by both chambers of Congress. Because the Galvez honorary citizenship movement was led by Republicans and the Galvez portrait movement was led by Democrats, perhaps there was a little rivalry going on here, with both sides using Galvez to flirt with Latino voters. But if that's true, I say bring it on! We need much more of that rivalry. There are many other U.S. Hispanic historical figures and accomplishments that need to be recognized. When she made Congress fulfill its 231-year-old promise, Valcarce said she was not only closing an unfinished chapter of American history but also showing "that Latinos indeed were involved before, during and after the creation of this wonderful nation." In fact, her powerful words can be confirmed through many other works of art throughout the halls of Congress. In the next chapter of the Great Hispanic American History Tour, we'll go exploring for much more Hispanic heritage, sometimes hidden right before our eyes in our nation's Capitol. To find out more about Miguel Perez and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com. COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM |

En español

|