|

Ninth of a series

There is absolutely no proof that Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was ever inside this ancient Native American (Tiwa) village known as Kuaua, and yet this place is officially called the "Coronado Historic Site."

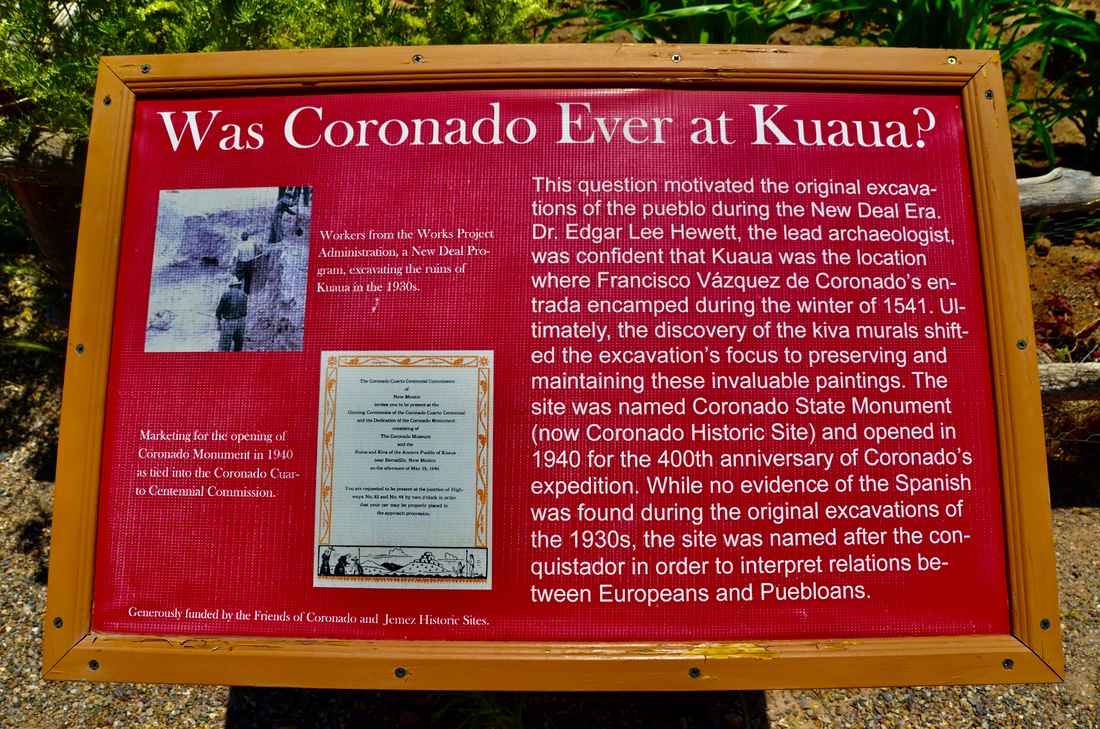

When you first arrive at these excavated village remains, 16 miles north of Albuquerque, along the west bank of the Rio Grande, in the interest of transparency (I guess), you are confronted by a sign that greets you with a question: "Was Coronado Ever at Kuaua?" |

|

If you don't know the answer to that question, you could be tempted to turn around and go back home. "Why am I here then," you might ask. And the answer to that question comes before you have time to turn around.

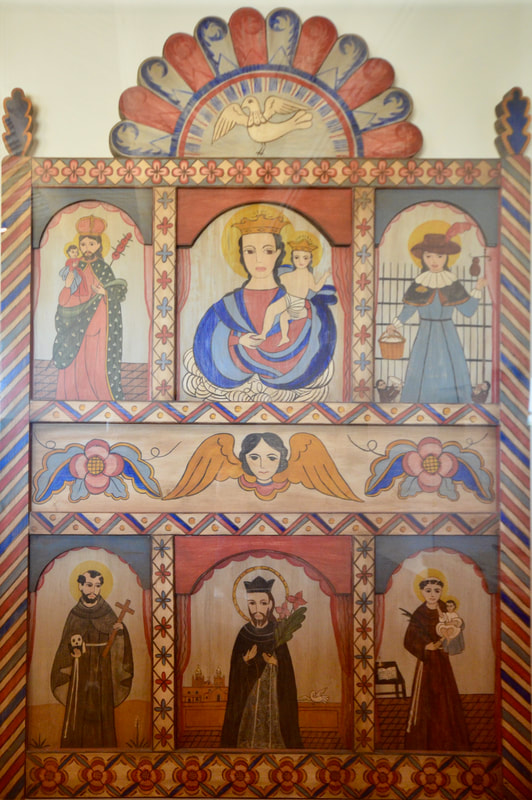

You learn that archeologists gave up looking for Coronado artifacts in Kuaua in 1930s, because they made another amazing discovery. At first, they believed that this is the place where Coronado's "entrada" expedition encamped during the winter of 1541. But in a square room (kiva) in the pueblo's south plaza, they found murals that are now considered among the finest examples of pre-European-contact art in North America. I can't show those images here because they don't allow photos to be taken in that room, but you can see some of them at their website. See the link at the bottom of this page. |

|

|

That's all great, you might say, but what about Coronado? The namesake of this place, did he or didn't come here?

As you walk a few steps further, another sign gives you part of the answer. That's where you learn that more than 80 years later, other archeologists using metal detectors, discovered dozens of Spanish military artifacts along the exterior walls of Kuaua. Some are now on exhibit at the site's visitor's center. Those archeologists concluded that "the layout and nature of these objects indicate that the Spanish briefly besieged Kuaua Pueblo during the Tiguex War of 1541." However yet another sign places the Spanish inside the village. It says that Kuaua "was undoubtedly visited by the Spanish." It explains that while the Tigua people first submitted to Spanish demands for food, shelter and clothing, "the demands of the army became unbearable," resulting in "a desperate revolt against the Spanish invaders in the winter of 1540-41. The results were disastrous for the pueblo people. Two villages were destroyed and many of the people killed." |

|

Frankly, I found the signs here a little confusing. First no evidence of the Spanish was found. Later, evidence was found outside the village, and then another sign has the Spanish inside Kuaua. This is part of state-governed Museum of New Mexico system, and I felt the self-guided tour needed to be clearer, better organized, a little less contradictory. lol

If you skip reading one or two of those signs (as I saw people doing), you will be totally lost, or at least unaware of the significance of what you are seeing. Bottom line: Coronado may have only reached the outskirts of what is now the Coronado Historic Site, or at least his soldiers did. And if they entered Kuaua, it was not a friendly visit, at least it didn't end that way. Yet, the Coronado State Monument (now Coronado Historic Site) was opened in 1940 for the 400th anniversary of the Coronado expedition. "While no evidence of the Spanish was found during the original excavations of the 1930s, the site was named after the conquistador in order to interpret relations between Europeans and Puebloans,” a sign says. So, as in most historic sites in New Mexico, here you learn about both Hispanic and Native American history. As you follow the site's trails, obeying signs warning you to avoid the rattle snakes, you learn the fascinating history of this ancient pueblo and the equally engrossing history of the Coronado expedition. "Archaeologists believe that a number of room blocks at this pueblo were two, and possibly even three stories high," another sign explains. "A family or household unit may have consisted of up to four upper story rooms used for storage of both food and household items. Since all entry to a household was from the roof, this would have provided both privacy and security for each household." |

|

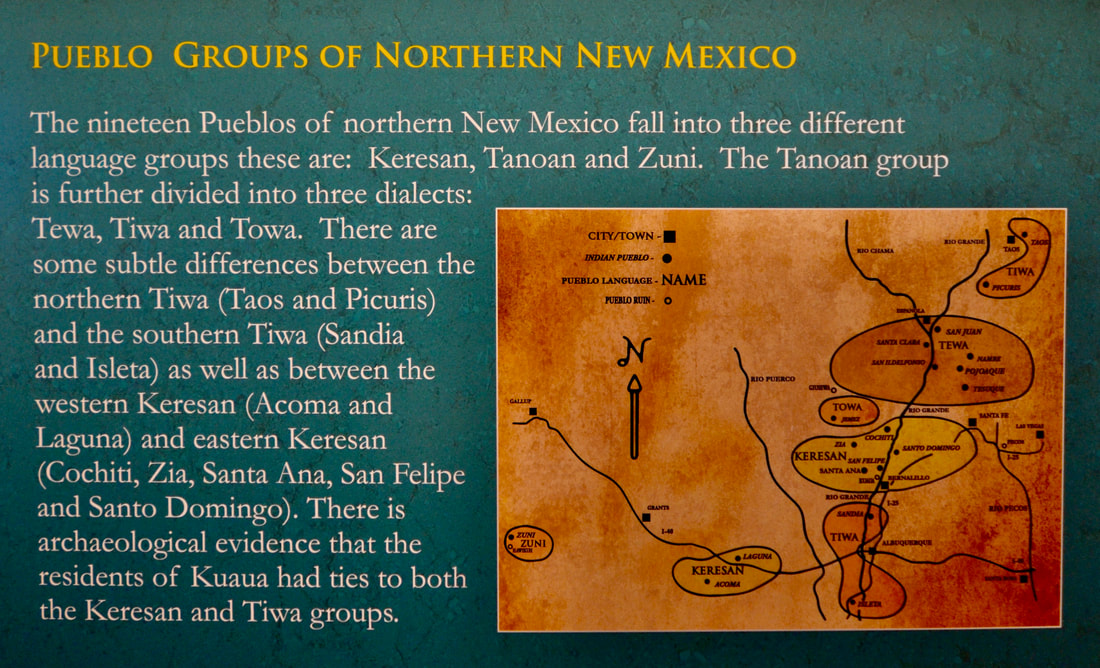

Here you learn that when the Coronado expedition came through this area in the 1500s, this village was already more than two centuries old. It was inhabited from 1300 to 1600. You learn that while some 1,200 rooms were unearthed by archeologists in the 1930's, many more remain unexcavated.

"The pueblo of Kuaua was abandoned around the beginning of the 17th century," another sign explains, while noting that "the exact reasons for abandonment are not known." |

|

Wikipedia tells us that "the village was almost certainly abandoned due to Coronado and the after-effects of the Tiguex War (February 1541)." It's always easy to blame the Spanish!

But when you get to the place where it all happened, you learn that there were several possible contributing factors to the pueblo's demise, and surprisingly, they don't only blame the Spanish: "A drought that lasted some 20 years until 1593," a sign says, "the disrupting influence of the Europeans, and warfare with nomadic Indian tribes." I was also surprised by signs displaying letters written by conquistadors and describing life in the pueblos. |

|

“We visited a good many of these pueblos,” wrote Gaspar Perez de Villagra in 1610. “They are all well built with straight, well-squared walls. Their towns have no defined streets. Their houses are three, five, six and even seven stories high, with many windows and terraces. The men spin and weave and the women cook, build houses, and keep them in good repair. They dress in garments of cotton cloth, and the women wear beautiful shawls of many colors. They are quiet, peaceful people of good appearance and excellent physique, alert and intelligent. They are not known to drink, a good omen indeed. We saw no maimed or deformed people among them. The men and women alike are excellent swimmers. They are also expert in the art of painting, and are good fishermen. They live in complete equality, neither exercising authority nor demanding obedience.”

|

|

Here you also get to see the Rio Grande, unspoiled by human development, as the conquistadors first saw it in the 1500s. In this country, many Americans associate the Rio Grande only with the U.S.-Mexico border. They don't realize that this great river turns north and cuts across New Mexico, and that it was the lifeline for Native American villages that were established, on both sides of the river, long before the Spanish arrived.

Those are the villages visited by the Coronado expedition from Mexico in 1540-41. And here you find the explanation for what really happened —both the failures and the accomplishments! “In spite of Coronado's accomplishments of exploring and opening up areas unknown to the European, the expedition was considered a failure," a sign explains. "For they had not found the fabled cities of gold, only mud villages." |

|

|

The markers tell us that this is the vicinity where Coronado fell from his horse and suffered an injury from which he would never completely recover. "When he returned to Mexico he found that his influence with the Spanish court had diminished," the sign explains. "He was brought to trial for mismanagement of the army and for cruelties inflicted upon the native peoples."

It goes on to explain that while Coronado was exonerated of those charges, "his significant contributions to the European settlement of the New World went unrecognized during his lifetime.” It still goes mostly unrecognized, unless you come to the Coronado Historic Site and read the signs very, very carefully. |

Coronado Historic Site website: https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/explore/coronado-state-monument/

|

Now I'm on El Camino Real on my way to Santa Fe and there is a church there that I have always wanted to visit. Can you guess which one? It's easy! It will be topic of my next article. Stay tuned!

|

To read other parts of this ongoing series, click: EXPLORING NEW MEXICO